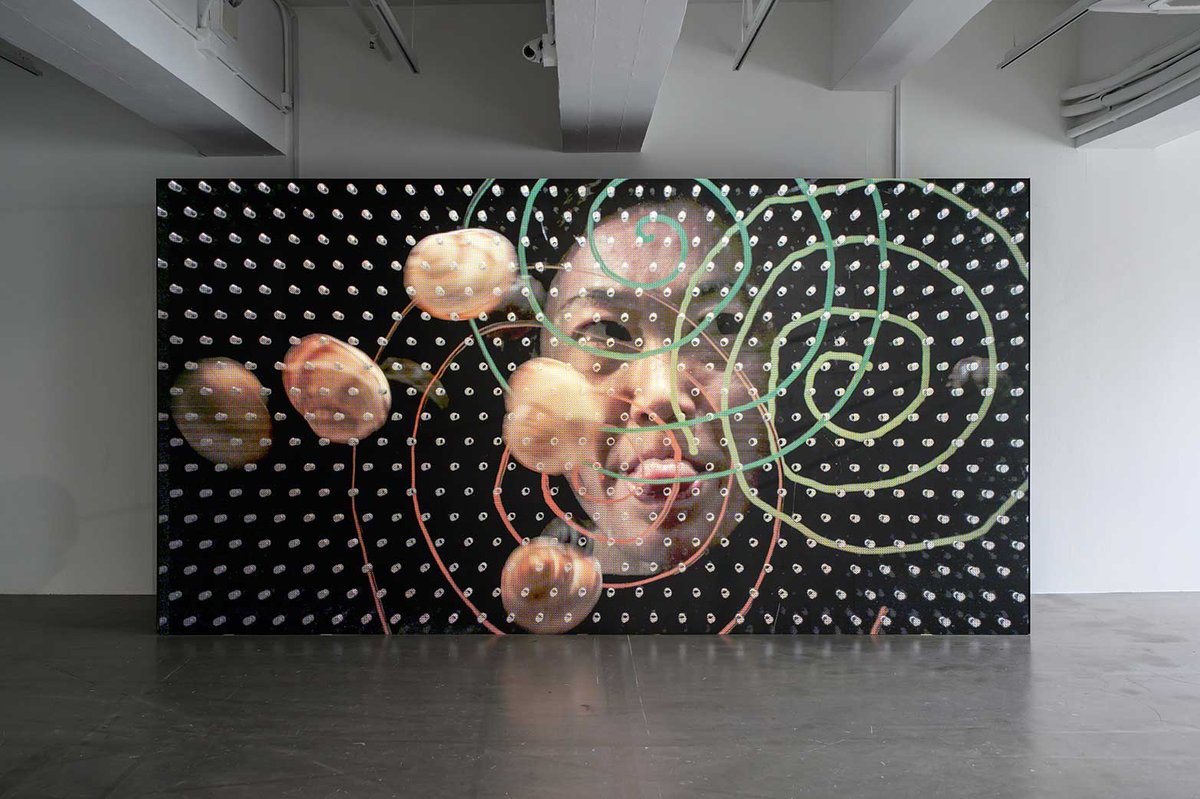

Over the past two decades, the Japanese artist Aki Sasamoto has developed a unique performance/installation practice in which she produces installations of absurd sculptural devices—from haemorrhoid cushions to oversized fishing lures—that, in turn, serve as an object-based score and environment for improvised performances that combine humorous spoken narratives with physical actions and mark-making. The artist’s first mid-career survey, Aki Sasamoto’s Life Laboratory at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (MOT), traces the evolution of this practice through a sharp combination of installations, documentation and live performances.

The Art Newspaper: You have a background in dance, you studied sculpture and your performances include a storytelling element. How do you see those strands coming together in your practice?

Aki Sasamoto: Dance and sculpture are very close for me. The relationship between one body and another is similar to that between a body and another entity that also occupies the space. Sometimes a body can act like an object, such as when someone stays still or moves slowly, while an object can move on its own, like when the weather changes or something breaks. The difference is that humans are more complicated psychologically, because I can empathise with how they feel.

As for storytelling, I like observing passersby or sitting in a café and listening to a breakup story from the next table over and then imagining what happened before and what comes after. But I never really articulated that interest until I happened to participate in an improvisational dance piece where the other participants were holding me up and I said something that summarised the situation and it made the audience laugh because it was so unexpected. Afterwards a choreographer who was in attendance chided me that I wasn’t supposed to utter a word while performing. That’s when I realised it would be interesting to work with language. I started making works where I suddenly said what I saw in the space as I was dancing. Then it expanded to looking at stand-up comedy and other language-based performances to figure out the links between object-making, dance and spoken word.

Did speech open up working with objects or did it all come together at once?

One of the choreographers I danced with was Yvonne Meier, who uses the score technique. She would give you a prompt—say, move as if a string were attached to your head—and then you had to dance it. This language-based movement practice was really influential for me and I apply it to sculpting now. How would you make something that looks happy or unhappy? How would you tilt something to create a scene? Take two beer bottles, for example. If the labels are positioned facing away from each other, it’s already a couple fighting.

People might describe a mid-career survey metaphorically as a biography of the artist. Since your works relate incidents from your own experiences, is your exhibition at MOT an actual biography?

As with stand-up, the self is a stand-in for me. My work is about 70% based on my own experiences, but I also incorporate other people’s experiences because it’s faster for getting to the core of what I want to share. It’s another type of editing.

The focus at MOT is not biography and more thinking about how to present, preserve and document performance. The curator Keiko Okamura and I wanted each work to represent a different approach. One is an object-based score, another incorporates a video camera in the installation and so on. Although it may look chronological, the idea is that each room presents a different way of considering the relationship between performance and object or performance and video.

What about the endurance side of staging a performance?

Once the installation is done I simply improvise within that structure. I have to make sure that the poles can accommodate my movements or that I can fit into the pipe or pull the paper smoothly. But I’m not creating anything during the performance. I’m simply playing the score. It’s like jazz. If I have the instrument I can just pull it out and play.

For the 59th Venice Biennale you made an installation, Sink or Float (2022), in which objects including snail shells, sponge cubes and plastic bottle caps perform, animated by an industrial fan. Within that framework the left-coiled snail shell becomes a figure for people who are different or—

Queer.

Yes, queer. What are your thoughts on the piece now, three years later?

It was a pivotal moment for me. Usually curators ask me to produce a performance, but Cecilia Alemani asked me to step back and let the objects shine. I took that homework seriously because the stand-in is a big question for performance. People ask me why I don’t have anyone else perform for me—after all, I’m going to die eventually. But I realised that, no, I want to believe in the objects’ ability to be a score, hence you could always imagine or preimagine the performance, and in that sense you could just let the objects perform on their own and the outcome would be similar. That gives the work an expanded lifespan beyond the human body. And I actually auditioned each of the objects as if they were dancers.

Was it important to represent a queer body in the piece?

It’s important to have a range of objects. Everybody has a character, and in a postmodern dance kind of way we accommodate them all. Nobody has to look like a ballerina. Everybody can bring their own movement. If you’re a construction worker, let’s use the movements you’re used to. The choreographer might embellish those movements or repeat them or slow them down, but they have to be true to your body and its history.

• Aki Sasamoto’s Life Laboratory, Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, until 24 November