Lagos Art Week isn’t just a calendar fixture—it’s an electric current. Traffic slows to a crawl as black SUVs weave between openings, horns blare, champagne flows and the city pulses with ambition and possibility. WhatsApp groups crackle with last-minute invites and secret listings. Everyone is everywhere as artists, curators and collectors crisscross the city in a whirlwind of movement and intent.

This year, it promises to be as sprawling as ever. Art X Lagos (6-9 November), the fair founded by Tokini Peterside-Schwebig in 2016, remains the week’s anchor and is celebrating its tenth year. Kó Art Space’s group show will spotlight artists inspired by the Oshogbo School, a 1960s Nigerian movement rooted in Yoruba mythology and intuitive creativity. Tiwani Contemporary is presenting sculptural pieces by the 37-year-old designer Nifemi Marcus-Bello, whose work is gaining international attention. “Lagos is in a unique moment,” says Marcus-Bello, who is based in Lagos and studied design at the University of Leeds, UK. This show is his first in Nigeria. “Contemporary design and art are redefined by a younger generation rooted in the local context yet globally attuned. What makes it exciting is the tension between tradition and innovation.”

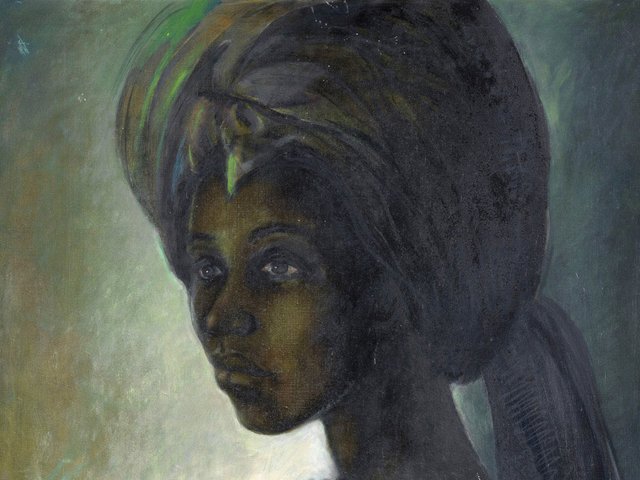

A work from the series Tales by Moonlight (2023) by Lagos-based designer Nifemi Marcus-Bello © 2023 Eric Petschek

Add in the activities of the Guest Artists Space (GAS) Foundation—established by the British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare in 2019—with its programme of talks, workshops and international cultural exchange, and Lagos feels confident and experimental.

To some, it might seem this moment appeared out of nowhere, that the “Lagos art boom” is a story of sudden discovery. But the roots go deep. Nigerian art wasn’t born of fairs or auction rooms, or the fever of market discovery. When I think of Nigerian art, I think of figurative terracotta Nok sculptures, or the Igbo-Ukwu bronzes—castings in metal made in the ninth century. But there’s also the restless spirit of Nigerian Modernism, a movement recognised at London’s Tate Modern this autumn in a show of the same name.

Lagos-based designer Nifemi Marcus-Bello Courtesy Marcus-Bello (Nmbello Studio)

I think of the Zaria Art Society, founded in 1958—a gathering of young artists including Uche Okeke, Bruce Onobrakpeya, Demas Nwoko and Yusuf Grillo (all of whose work will be at Tate Modern), who were called rebels for daring to imagine a future in which Nigerians could speak in their own voice. They turned away from borrowed narratives and instead dug into the red earth of tradition to reveal symbols, patterns and stories that could better represent a modern nation with its own deep history.

They saw independence not just as political liberation but as cultural, and they wove historical motifs, Yoruba carvings and Hausa arabesques into a Modernist vocabulary and a self-defined identity. Onobrakpeya’s etchings, with their textured layers of folklore and spirituality, and Okeke’s abstract lines derived from Uli—the traditional Igbo practice of drawing intricate designs on the body and walls in natural dyes—were not about nostalgia but about vision. These works were declarations: Nigerian art would not imitate; it would innovate.

Lagos artist Nengi Omuku with her 2024 exhibition The Dance of People and the Natural World at Arnolfini, Bristol © Nengi Omuku 2025; Photo: Lisa Whiting.

Intellectual and artistic revolutions

The Mbari Artists and Writers Club in Ibadan, founded in 1961, gave this vision a home. It was never just a club—it was a cultural salon where Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe and Christopher Okigbo debated what a Modern Nigerian aesthetic could be. The Tate Modern exhibition promises to revisit the intellectual and artistic revolutions of this era, to place figures like Okeke, Onobrakpeya and Grillo in their rightful context—not as regional Modernists but as the innovators of a mid-century experimentation that has shaped our aesthetic vocabulary and cultural independence.

Lagos Art Week offers a window into the momentum of Nigeria’s contemporary scene, which is shaped not by a handful of stars but by a growing constellation of artists, galleries and curators. “Over the past ten years or so, Nigeria’s art scene has really grown,” says Nengi Omuku, who paints her responses to issues of heritage and the inner psychology of her subjects on sanyan, a tightly woven Aso-oke fabric made by the Yoruba people. “There is a surge in practising artists and more galleries able to showcase their work locally.” Omuku, though she lives in Lagos, is represented by Kasmin Gallery in New York and Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in London. “Equally important is the increase in private collectors, especially those who lend work or allow visitors to their collections,” Omuku adds.

Nengi Omuku’s Sea Breeze (2025) © Nengi Omuku 2025. Photo: Todd White

Indeed, Lagos Art Week isn’t complete without the generosity of those who open their doors. There’s Femi Akinsanya, whose collection spans ancient sculptures to Modern masters and reads like a timeline of African art itself; or Kavita Chellaram, who started collecting Nigerian Modernists in the late 1970s and invites visitors for tea. The financier Adeniyi Adenubi has wonderful works by Demas Nwoko, including Nightclub in Dakar (1963), hanging in his home.

The rise of the market from the mid-2000s transformed the terrain of Nigerian art. When Chellaram launched Arthouse Contemporary in 2007—an auction house specialising in Modern and contemporary West African art—she helped to establish a transparent secondary market. Previously, serious collectors were few and prices hovered in quiet opacity. Early auctions brought works by Ben Enwonwu, Onobrakpeya and Grillo into sharper focus, placing them under the hammer of history. Paintings that changed hands for 1.5m Naira ($1,000) in 2008 approached 20m Naira ($13,000) a decade later. Today, contemporary Nigerian artists like Njideka Akunyili Crosby command nearly $3.4m, marking the market’s global reach. (Crosby, working out of Los Angeles, could equally be considered a global artist.)

The appetite for Nigerian art has, however, brought into sharper relief the pressures faced by the country’s public institutions, which often work with limited resources, yet remain key custodians of cultural heritage. Enwonwu’s Tutu (1974), rediscovered and sold for £1.2m at Bonhams in 2018, should be a national touchstone. But it is not hanging in a Nigerian museum; it is in a private collection.

A new generation of collectors

If Nigerian art continues to be treated primarily as an export, we risk repeating extractive dynamics in more glamorous packaging, so the importance of seeing it in Nigeria is paramount. Art X Lagos is throwing a spotlight on J.D. ’Okhai Ojeikere, whose lens captured the elegance of everyday life in post-independence Nigeria—from hairstyles to architecture and ritual. Local audiences will get to see an array of Ojeikere’s work, much of it lent by private collectors, some from abroad.

In that same spirit, the Nigeria Pavilion—which I curated at the Venice Biennale in 2024—will be shown at the Museum of West African Art (MOWAA) when it opens in Benin City later this year. It is coming home not as a spectacle, but as an offering: to root Nigerian art where it belongs, in the soil of its own story.

Ben Enwonwu’s The Durbar of Eid-ul-Fitr, Kano, Nigeria (1955). © Ben Enwonwu Foundation.

The new generation of collectors—tech entrepreneurs, financiers, diasporic returnees—have the capacity to help. We need patrons to fund residencies, institutions and archives and keep important works circulating in Nigeria. When I think of what we’ve inherited—from Okeke’s vision of a Nigerian Modernism to the 93-year-old Onobrakpeya’s belief in art as a vessel for identity (the son of a Urhobo carver, his innovative etchings are in the collections of the Vatican Museum in Rome and London’s Victoria and Albert Museum and Tate Modern)—I feel both admiration and urgency. We are standing on the shoulders of giants.

Yinka Shonibare’s Monument to the Restitution of the Mind and Soul (2023) at the Nigeria Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 2024 Marco Cappelleti Studio; Courtesy Museum of West African Art (MOWAA)

“I love being an artist in this city,” says Chidinma Nnoli, a Lagos resident who challenges misogyny and the patriarchal system in her paintings. “And I’m hoping for deeper, more sustainable support systems that don’t just spotlight artists when it’s convenient, but actually walk alongside us as we build. But now, the artists themselves are creating spaces. Collectives are forming, critical discussions are taking place in spaces like Kuta Arts Foundation by Benita Nnachortam and A Third Space by Nelson C.J, which is rethinking how people, not just artists, gather.”

Enwonwu’s Tutu (1974), which sold at Bonhams for £1.2m in 2018 Courtesy Bonhams

Later, I’m sitting cross-legged in the studio of artist and photojournalist Yagazie Emezi in Lekki, south of Lagos. We sip zobo as sunlight filters softly through the plant-lined windows. “Nigeria feels alive with possibility—as it always has,” Emezi says. “But I’m excited to see us turning inward, reclaiming our roots and bringing the past gently into the present.”

• Art X Lagos, 6-9 November