A new exhibition opening at the National Museum (Nasjonalmuseet) of Norway in Oslo this week breaks new ground by exploring a challenging art historical subject: queer desires and practices in the visual cultures of the Islamic world. Deviant Ornaments (27 November-15 March 2026)—curated by Noor Bhangu, a South Asian curator and scholar based in Norway—brings together more than 40 works from the past 1,000 years, connecting historical traditions and items with the works of 12 contemporary artists such as London-born Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and Toronto-based Alize Zorlutuna.

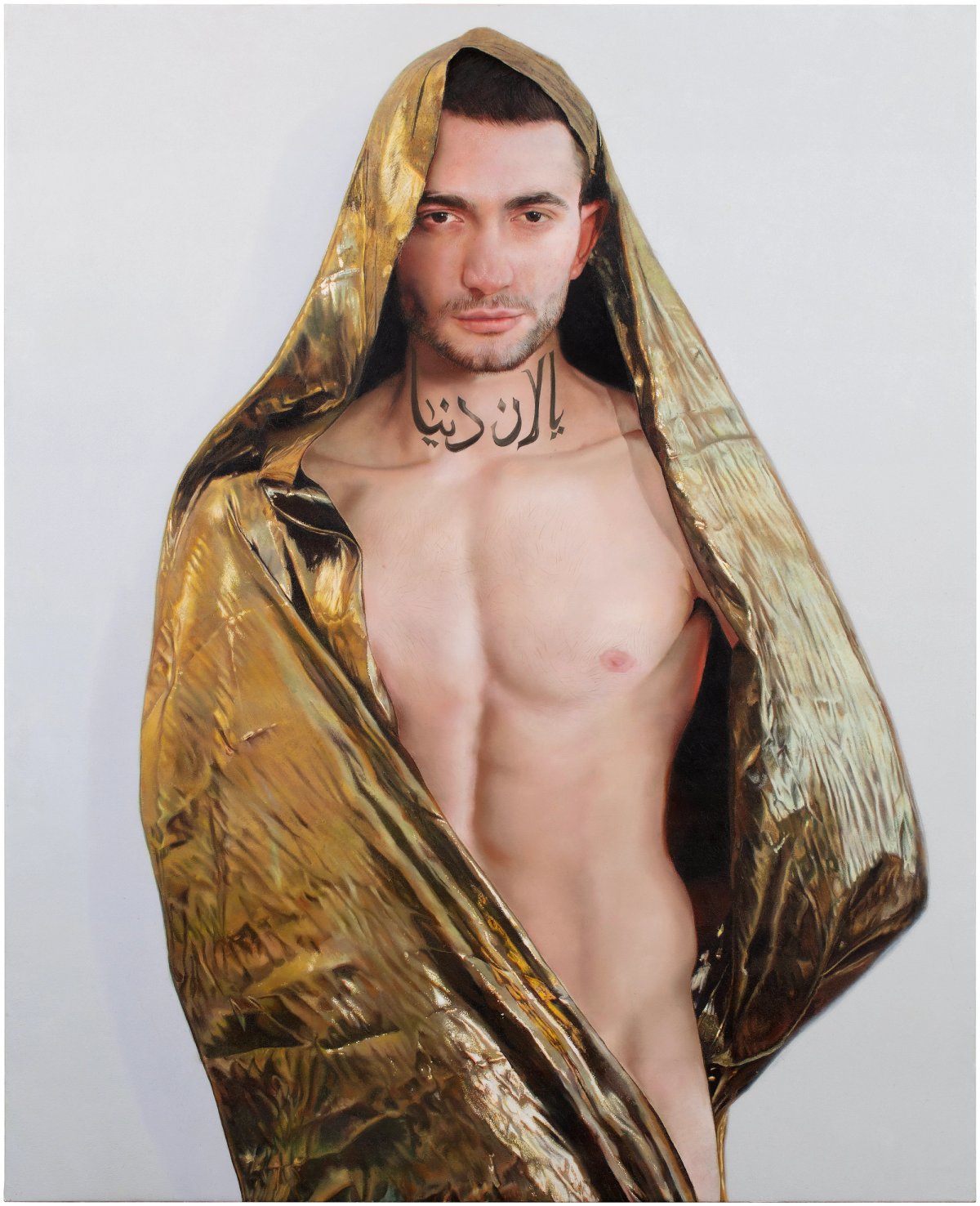

Artist Shahzia Sikander’s bronze figures, Promiscuous Intimacies (2020) combine South Asian and European traditions, depicting an 11th-century sandstone sculpture of a Devata, a divine deity, and the figure of Venus from Agnolo Bronzino’s An Allegory with Venus and Cupid (1540-46). Turkish artist Taner Ceylan’s Fake World painting (2011) shows a semi-nude male figure clad in a gold robe.

Shahzia Sikander's Promiscuous Intimacies (2020) © Shahzia Sikander. Photo" Adam Reich, courtesy Sean Kelly, New York / Los Angeles

“Our hope is to visualise a queer genealogy of Islamic art history, through which the public gains insight into diverse cultures of sexuality that have unfolded across the historical and contemporary Islamic world. In the contemporary Islamic world, we are also bringing into relation queer diasporas across North America, Europe and other parts of the world,” Bhangu tells The Art Newspaper.

The exhibition timespan covers a millennium because “the over-reliance on contemporary works [in other projects and exhibitions]… suggests that homosexuality and queer desires are solely the products of the current postcolonial era [and] thus inheritors of only Western models of sexuality”, adds Bhangu.

Historic objects featured include a Safavid textile by an unknown artist (1567); Ali Ghulam Khanezad’s Armband with gold and enamel inlay (around 1820), which depicts Prince Tahmasp Mirza, grandson of the ruling 18th-century Fath Ali Shah in Iran; and two wall tiles dating from 13th-century Iran, drawn from the National Museum’s collection.

Ali Ghulam Khanezad's Armband with gold and enamel inlay (around 1820) Photo: The David Collection / Pernille Klemp

The show also includes four commissioned works by France-born Damien Ajavon, the performance artist Rah Eleh, the Iranian artist Kasra Jalilipour and Ohio-based Sa’dia Rehman. Ajavon’s textile installation, Chemin vers Oslo (2025), and a 19th-century embossed gold belt buckle with the Hand of Fatima reflects the “palpable” relationship between historical and contemporary Islamic art, says Bhangu.

“Ajavon has incorporated several small Hands of Fatima into their work, some of which I brought back from my visit to Pakistan as a relational gesture. Most of Damien’s ornaments are silver, creating a compelling contrast with the 19th-century work, through which we can visualise both the continuities and discontinuities between the passing down of artistic and symbolic traditions.”

Left and centre: Damien Ajavon's Chemin vers Oslo (2025); right: an embossed gold belt buckle with hands of Fatima by an unknown artist (1800s–1900s), from the collection of the Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture & Design Hawaii Ajavon: © Damien Ajavon / BONO. Photo by Annar Bjørgli / The National Museum; belt buckle: photo by Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture & Design

Queer depictions in Islamic art are considered sensitive because homosexuality is considered taboo, and in many cases illegal, in most Muslim communities. The show aims to enlighten audiences, highlighting issues around religious sensitivities. “When spiritual elements are introduced through the dissemination of the works, like references to Sufism or the protective motif of the Hand of Fatima, we are clear about situating these within a historical and cultural context, not only in a spiritual one,” says Bhangu.

There are some works in the exhibition that touch on traumatic or difficult histories, such as Orientalist depictions of racialised people, she adds. “I think it is important to include these colonial references because Orientalist narratives had an enormous impact on local cultures of sexuality in the Islamic world.

“When people from the Islamic world saw these visual depictions and textual materials based on travel accounts, they felt shame… this resulted in erasure of homoerotic pasts and the straightening of homoerotic archives; take for example wine poetry or ghazals dedicated to joys of homoerotic desire.”

Ingrid Røynesdal, the director of the National Museum, says in a statement: “Museums must be spaces of curiosity, learning and debate; with this exhibition, we proudly open that space to the world.” Bhangu stresses that Deviant Ornaments is a “love letter” to queer relations across geographies and generations.

- Deviant Ornaments, Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo, 27 November-15 March 2026