The 14th-century Asante Ewer, which was made in England and then mysteriously travelled to West Africa, is expected to be loaned to Ghana next year. It had been looted from the royal palace in Kumasi in 1896 and was then acquired by the British Museum in London.

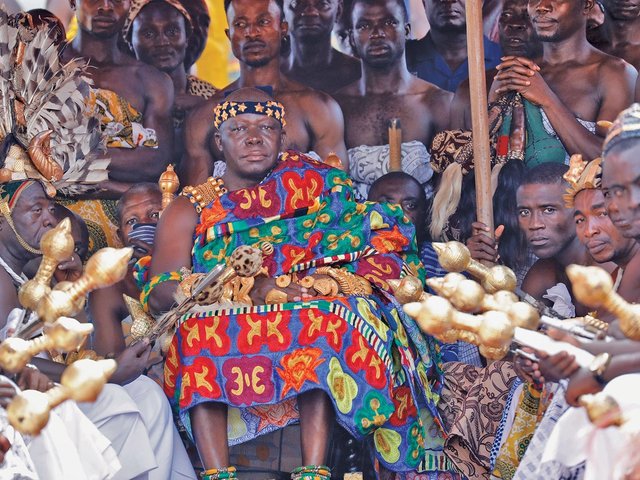

Ivor Agyeman-Duah, the director of the Manhyia Palace Museum in the Asante (or Ashanti) capital of Kumasi, plans to travel to London early this month to request the ewer. He tells The Art Newspaper that he will then make an “official” loan request. This is likely to be formally requested on behalf of Asantehene (king) Otumfuo Nana Osei Tutu II.

There have been informal discussions and the British Museum is apparently open to such an arrangement. It would be a long-term loan, which would normally be for a three-year period. By agreeing to a loan, the Ghanaian authorities would effectively be acknowledging the British Museum’s ownership, apparently ruling out any claim for permanent restitution.

Relations between the London and Kumasi museums are co-operative, so a loan should be smoothly arranged. Both the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London have already lent other looted artefacts to the Manhyia Palace Museum since last year.

In October the Asante Ewer was lent for the first time since its acquisition in 1896, when it went on display at York Army Museum (until 21 February).

In York it is being shown with two smaller ewers, both of which were almost certainly of British origin. They too ended up in Kumasi, where they were looted in 1896 and 1900. One (right, in image) is also in the British Museum’s collection, and the other (left) is deposited at the York Army Museum (from the Prince of Wales’s Own Regiment of Yorkshire).

An 1884 photograph of the royal compound in Kumasi in modern-day Ghana shows the Asante Ewer Photograph by Frederick Grant; Credit: Foreign and Commonwealth Office Library

The British Museum now acknowledges that the Asante Ewer was loot, a term the institution would not have used until recent years. In an “object in focus” book, just published, the Asante Ewer is acknowledged as “looted”.

The book concludes that the Asante Ewer may have been “displayed at medieval feasts”, then transitioned from “a highly regarded ritual object in the courtyard of the Asante king’s palace to a looted war trophy and museum acquisition”.

The intriguing question is where the Asante Ewer ought to go to when it returns to the British Museum in a few years. Should it be in the medieval European gallery, where until recently it has been displayed? After all, it was made in England, quite possibly for a king, and is a rare survival from more than 600 years ago. Or should it be in the Africa galleries? In the Asante kingdom it became a sacred object, kept, perhaps for centuries, in a royal palace.

A brief history of the Asante Ewer

The Asante Ewer is one of the most intriguing objects in the British Museum. Standing 62cm high, the ewer is the largest surviving bronze vessel made in medieval England. Holding 19 litres, it may well have been made for serving wine at a grand feast, although it would probably have required two people to lift it. The British Museum dates the ewer to between 1340 and 1405. It bears the royal coat of arms and may well have been made for Richard II.

The Asante Ewer (around 1390–1400) © 2025 The Trustees of the British Museum

How the ewer reached the Asante kingdom remains a mystery, despite the recent research. The two British Museum curators who have recently studied it have slightly different views. Lloyd de Beer believes it more likely that the ewer was taken by sea around the West African coast, possibly by an early trading ship. Julie Hudson is inclined to the theory that it was carried across the Sahara by a camel caravan.

Despite considerable recent research, it also remains undetermined when the journey occurred, although this may well have been in the 14th or 15th centuries, soon after the ewer was made. All that is certain is that the Asante Ewer was in a royal palace in Kumasi in 1884, when it was photographed in a courtyard by Frederick Grant. At that point it appears to have been regarded as a sacred object.

The ewer was seized by British troops in 1896, during extensive looting in the fourth Anglo-Asante war. It was immediately auctioned off by the military authorities and bought by Charles St Leger Barter. He realised the ewer was British, because of an inscription in old English, but speculated in a letter to the British Museum that it had first gone to western Asia: “It may have been taken by the Crusaders to Palestine & from there worked its way through Africa, after capture by the Saracens.” Barter quickly sold the Asante Ewer to the British Museum for £50, where it has always been displayed as an English medieval masterpiece.