Art heists always capture the imagination—just ask officials at the Musée du Louvre—and the theft of a Rembrandt in 1975 was no exception. On 14 April 1975, Myles Connor entered the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston in disguise along with an accomplice. The pair went directly to the Dutch Gallery and proceeded to remove Rembrandt’s Portrait of Elsbeth van Rijn from the wall. Connor, an experienced career criminal, eventually used the Rembrandt as a get-out-of-jail-free card for another crime, namely the theft of works by the artist duo Andrew and N.C. Wyeth.

In his new book, Anthony Amore delves into Connor’s life and adventures as an art thief, outlining why the Rembrandt robbery mattered. As well as being an author, since 2005 Amore has been the director of security and the chief investigator at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston—the site of one of the most renowned unsolved art thefts in 1990, when 13 works, including pieces by Rembrandt, Johannes Vermeer and Edgar Degas, were stolen.

Here, Amore takes us on a tour of another infamous heist and shares five takeaways from his new publication The Rembrandt Heist.

Anthony Amore Seth Jacobson

1. Beg, borrow or steal

While the inspiration behind nearly every art heist is money, Connor’s motivations were unusual. For instance, he once robbed a museum of dozens of pieces from its collection because they had insulted his father. And the titular heist was not because he hoped to sell or enjoy the Rembrandt painting itself. Rather, he wanted only to borrow it for a while. So while contemporary investigators can start with certain assumptions about major heists, they must not ignore possibilities that do not fit a profile.

2. Professional art thief

The term “professional art thief” is something of a misnomer. In most cases, people who steal art, especially highly valuable works, are common criminals who steal all manner of things. Museums present an attractive target because they are the rare institutions that hold huge assets and invite the public in to get up close and personal with them. However, because selling highly recognisable works is typically more difficult than stealing them, thieves rarely do it more than once. Therefore, it is not a profession at all. Very few people steal masterpieces more than once because they quickly learn folly of the effort. This makes Myles Connor another sort of outlier; by his count, he robbed more than 30 museums.

Rembrandt’s Portrait of Elsbeth van Rijn, which Connor stole from the MFA Boston Courtesy of the Leiden Collection

3.Art lover, conman or connoisseur?

While the vast majority of people who steal art are not, in fact, art lovers, Connor is very knowledgeable about art and antiques. From a young age, his maternal grandfather took him to the MFA Boston, teaching him about the holdings. Connor’s grandfather was a connoisseur who travelled to Japan often with intellectuals from New England just as that nation was opening itself up to trade and educating foreign visitors about its culture. Connor developed an affinity for Asian artefacts that has lasted his entire life. Coveting his own pieces to complement that which his grandfather left to him was at the root of many of his heists.

4. The way of the samurai

Though one of the most notorious criminals in the history of the US, Connor is well known to abide by a strict honour code, no doubt inspired by his studies of the way of the samurai. The code mandates that he will never turn informant; never harm a child, a woman, or the elderly; never steal from a friend or the needy; and never betray or deny a friend in need. This last bit is an important part of the story of the Rembrandt that he took from MFA Boston. Connor’s lifelong best friend, the music manager Al Dotoli, shared this code with him despite not being a criminal. Rather, the friendship resulted in Dotoli’s decision to help Connor at his greatest moment of need despite placing himself and his business in great peril.

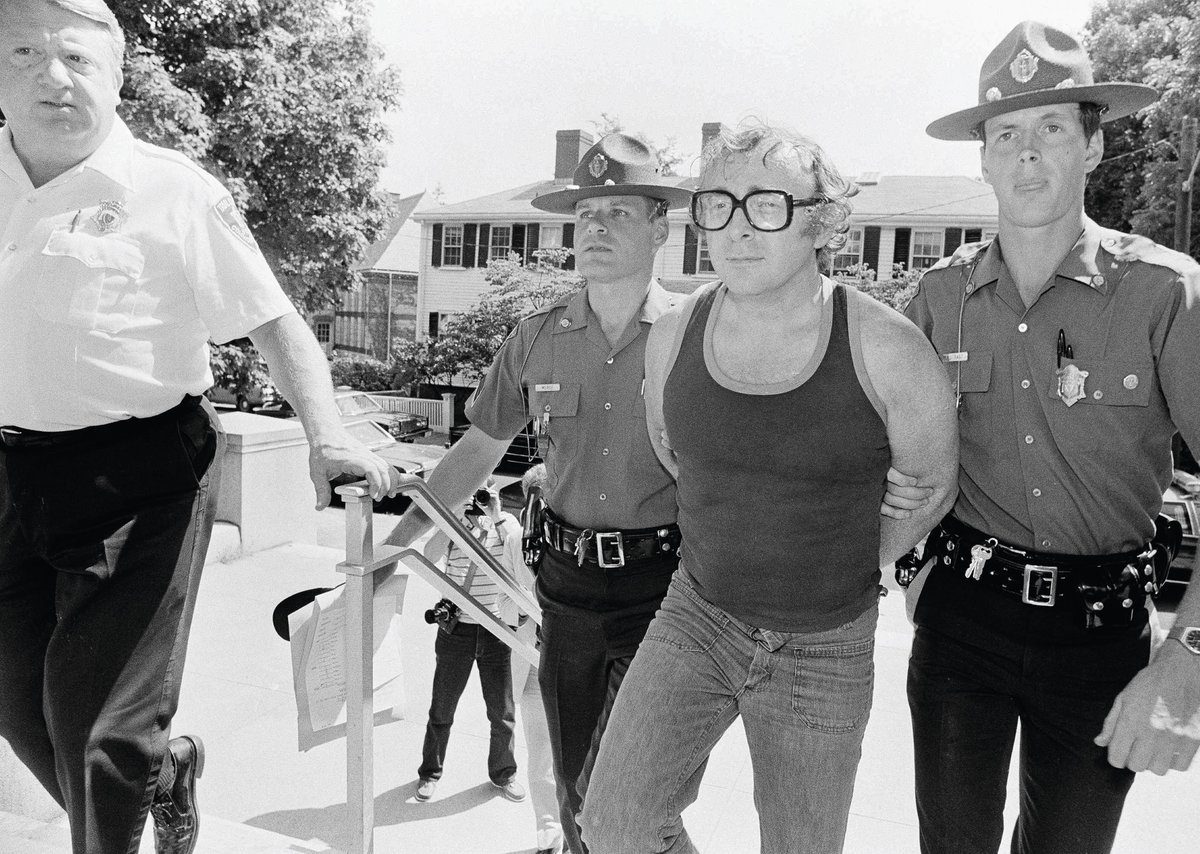

Connor holding one of his newly acquired swords during a lunch with Amore Photo courtesy of Anthony Amore

5. Path of least resistance

For a person to be consistently successful, they must also possess a steady hand and no shortage of audacity. Connor often posed as a PhD student and approached museum curators to gain their confidence. Once he accomplished this, he would talk his way into being left alone in several collection storage spaces, from which he would pilfer what appealed to him. The path of least resistance is always the one chosen by successful criminals, and Connor exemplifies this best because his sharp intellect allowed him to develop methods for finding that path.

• The Rembrandt Heist, Anthony Amore, Pegasus Books, 272pp, $29.95 (hb)