It is nearly showtime for the sixth edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (KMB) in Kerala, southern India, which is scheduled to open on Friday 12 December and runs until 31 March 2026. For the Time Being is curated by the artist Nikhil Chopra and his Goa-based collective HH Art Spaces, who have invited 66 artists or artist groups to “work with Kochi’s climates, conditions and resource realities to make time, think nimbly, and collaborate locally”, they said in a statement. (A full artist list can be found here).

Who is taking part?

Chopra is well known for his performance work and fittingly he has enlisted some of the medium’s biggest names to take part in the show. Chief among them is Marina Abramovic, who will deliver a lecture performance on 10 February, as well as exhibiting Waterfall (2003), a large multi-channel video installation of 108 chanting monks and nuns. Another performance art pioneer Tino Sehgal will show three of his collaborative live works, which he terms “constructed situations”, including Kiss (2003), in which two performers lie on the floor locked in a sensual embrace.

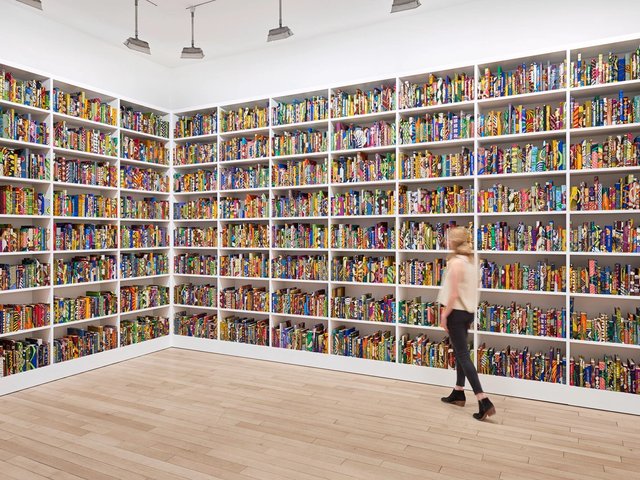

Other major international names taking part include Otobong Nkanga, who has planted a tropical garden that will grow throughout the show’s run. Ibrahim Mahama, who topped the latest ArtReview Power 100 List, will show his installation Parliament of Ghosts (2019-ongoing) of salvaged chairs arranged to resemble a parliamentary hall. Iterations of this work, initially commissioned by the Whitworth Museum in Manchester, have been shown at the 2023 São Paulo Biennial, the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennial, and the Ibraaz Foundation in London. And Adrián Villar Rojas will revisit his Rinascimento sculptures (2015-ongoing): functioning freezer drawers glutted with striking compositions of fresh and pre-packaged food in varying stages of decay.

South Asian artists will comprise around two-thirds of the show. Among the most prominent are Bani Abidi, who has teamed up with the architect Anupama Kundoo to design a hospitality space in which a simple Keralan lunch will be served every day. The work extends a practice of hosting “solidarity dinners” that Abidi, who is based in Berlin, began two years ago, following the outbreak of “genocide in Gaza”, reads a curatorial note. Meanwhile, a survey of Jyotti Bhatt will bring together paintings, drawings and woodcuts spanning seven decades of his career. Naeem Mohaiemen will present a new video work that intersperses footage of the aftermath of the 2024 July Revolution in Bangladesh with cinema made around the 1971 Liberation War.

They are joined by fast-rising names from the subcontinent such as Prabhakar Kamble, Biraaj Dodiya and Birender Yadav, the latter of whom will show an installation filled with clay casts of personal belongings left behind by migrant brick workers in their temporary homes.

Abidi is one of two artists from Pakistan, along with Huma Mulji, to be included, a notable feat in India considering the dire relations between the two nations. Contentious political subjects will also be broached in the biennial, despite a growing climate of political censorship in India. Moonis Ahmad Shah will show several video works that criticise India’s brutal occupation of Kashmir and the abrogation of the region's semi-autonomous status in 2019.

Where is it taking place?

The fate of Aspinwall House, a sea-facing heritage property that has served as the central site for the biennial since its launch in 2012, has been the subject of speculation in the run up to the exhibition. During the previous edition, the calamitous last-minute decision by the biennial's organisers to postpone the opening was blamed partly on the real estate developers DLF blocking access to the building and delaying the installation process.

A spokesperson for the biennial confirms that part of Aspinwall House will be used an exhibition venue for this edition. “The portion available to KMB is owned by the Government of Kerala and covers a substantial section of the property from Calvathy Road to the river. Aspinwall House still functions as the primary venue of the Biennale."

However, a significant part of Aspinwall House remains under negotiation and will not be available to the biennial. Its organisers have instead expanded the show to several new venues. Chief among these is Island Warehouse on Willingdon Island, which is accessible by a ferry from the main biennial sites.

Who is funding it?

The biennial is organised with a projected budget of $3.3m but faces diminished resources from the state of Kerala. Private donors are increasingly relied upon to fill the gap. The chief private funders for this edition, who have paid between 5m to 10m rupees (around $55,000 to $110,000) each, are Yusuff Ali, Minal Bajaj, Aarti Lohia and Mariam Ram.

Meanwhile, a new category of donors, titled "benefactors", have been instated to provide greater year-round support for the biennial, which will reduce the need to launch time-consuming fundraising rounds for future editions. The following "platinum benefactors" have committed to donating 10m rupees (around $110,000) to the Kochi Biennial Foundation over the next five years: Sangita Jindal, Kiran Nadar, Mariam Ram, Shabana Faizal, Shefali Varma, Anu Menda, and Adeeb and Shafina Ahmed.

As with many biennials, commercial galleries play a central role in providing funding and organisational support. Galleries that have donated to this edition of the biennial include Chemould Prescott Road, Vadehra Art Gallery, Mirchandani + Steinruecke and Akar Prakar.

Several of India's galleries are well represented by multiple artists in the show. Jhaveri Contemporary, whose co-founder Amrita Jhaveri sits on the Kochi Biennale Foundation board of trustees, counts four of its artists in the exhibition: Matthew Krishanu, Monika Correa, Sayan Chanda and Lionel Wendt; it has also exhibited the participating artists Shiraz Bayjoo, Prabhakar Kamble and Kirtika Kain.

Other galleries with sizeable presences at Kochi are Experimenter, with five artists: Naeem Mohaiemen, Bani Abidi, Vinoja Tharmalingam, Biraaj Dodiya and Bhasha Chakrabarti. And Chatterjee & Lal which represents Minam Apang, Nityan Unnikrishnan and the biennial’s curator.