In her 2002 autobiography, Infinity Net, the Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama describes going to extraordinary lengths to leave Japan in the 1950s, including sewing banknotes into her clothes and shoes. Once in Manhattan, she lived off market-stall scraps and sometimes nothing at all for days on end. Only her commitment to a “revolution in art”, she writes, got her through the hunger and destitution, not to mention the opposition she encountered from what she thought of as a profoundly conservative art establishment.

“Action painting was all the rage then,” she writes, “and everybody was adopting this style and selling the stuff at outrageous prices. My paintings were the polar opposite in terms of intention, but I believed that producing the unique art that came from within myself was the most important thing I could do to build my life as an artist.”

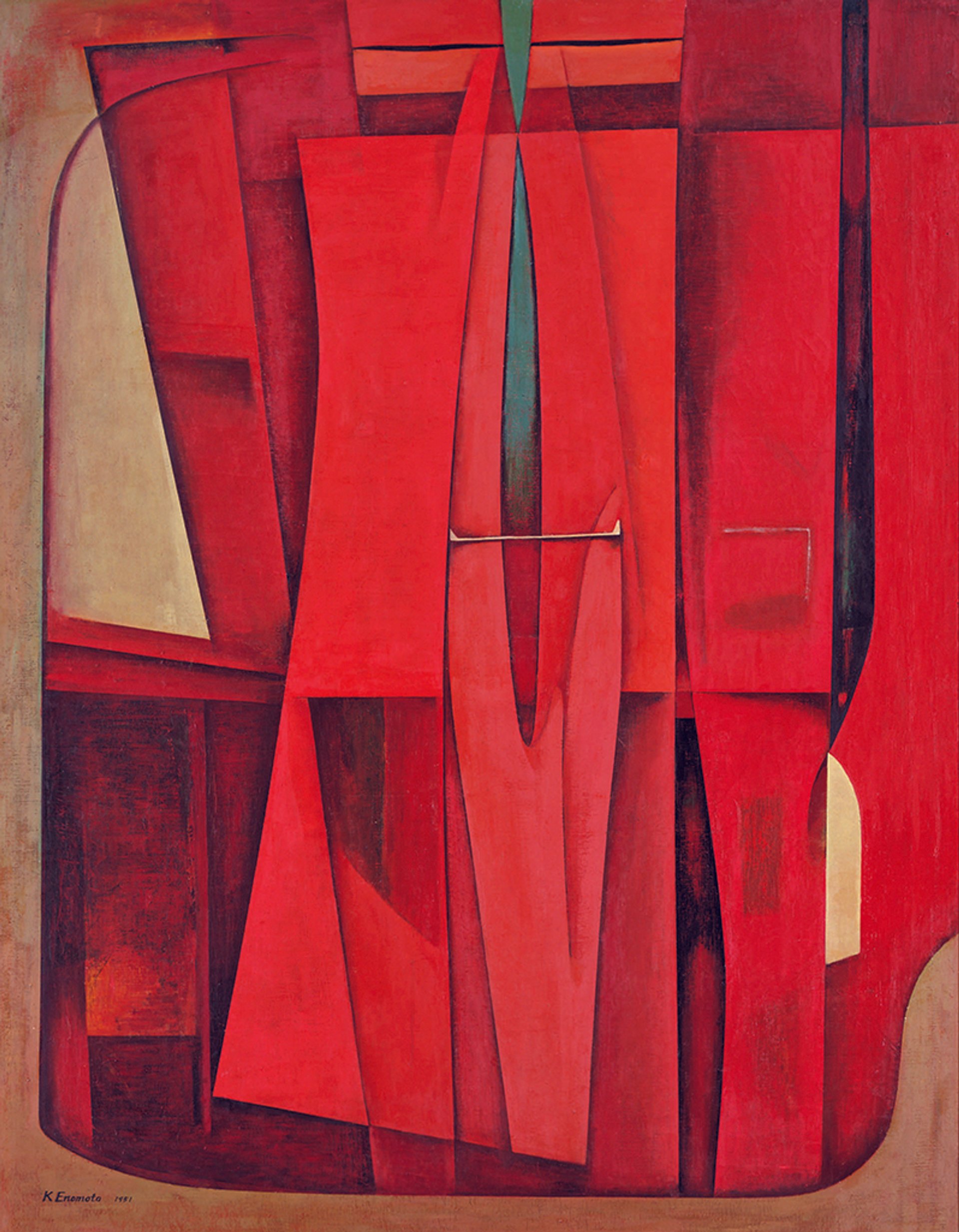

Kazuko Enomoto’s Section (I) (1951) © the artist, courtesy Itabashi Art Museum

Anti-Action: Artist-Women’s Challenges and Responses in Post-war Japan, opening this month at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (Momat), demonstrates how Kusama’s stance finds a distinctive echo in that of many other women artists working in Japan in the 1950s and 1960s. The art historian Izumi Nakajima coined the term “anti-action” to refer to these artists’ disparate practices, which are not connected by common themes so much as a common fight—a fierce determination to do things differently.

Alongside Kusama are Atsuko Tanaka and Tsuruko Yamazaki—both part of the more male-dominated Gutai movement—and the avant-garde painter Hideko Fukushima. That the names of the ten other artists included in the exhibition have been forgotten speaks to how the art critics of the day responded to their work, says Momat curator Hajime Nariai.

Upending the pre-war regime

The 1950s were a time of immense upheaval for Japan. The Allied occupation of the country was brought to an end by the signing of the San Francisco peace treaty in 1951. Japan’s post-war constitution (drafted in part by the US) sought to upend, among other things, the pre-war regime of gender inequality—whose strictures Kusama refers to when she cites how she was “dying to escape the chains that bound me”.

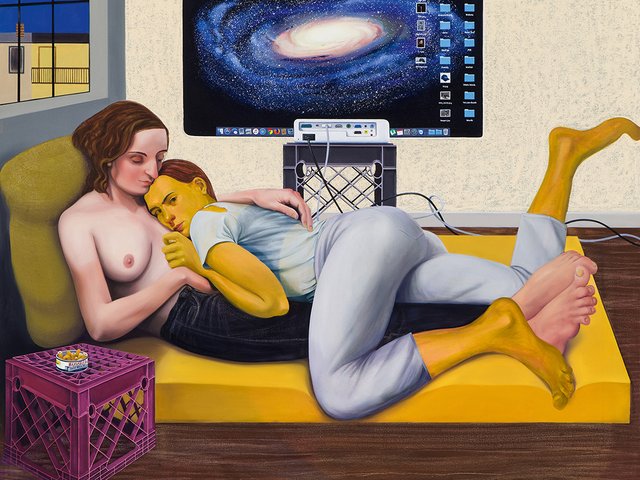

Kinuko Emi’s Festival of Space (1963) © the artist

In Japan, young women, in particular Fukushima and Tanaka, found inspiration in the French critic Michel Tapié’s Art Informel movement. “Within Informel, it didn’t matter who the artist was, which country they were from, whether they were a man or a woman,” Nariai explains, “what mattered was the work itself, the texture, the method.”

Japanese critics, however, took issue with the Eurocentrism of Tapié’s ideas, cleaving instead to the more masculine ethos of action painting. “Notions of femininity persisted,” Nariai says. “In art criticism, ideas that women wouldn’t create large-scale works, or that women were inherently delicate, were extremely common.” Art historians subsequently adopted the critics’ language from that era. “Exhibitions weren’t held, research wasn’t done, and many female artists were forgotten,” Nariai says.

That biased telling of art history belies how successful these women artists were in their day. Kinuko Emi was the first woman to represent Japan at the Venice Biennale, in 1962, exhibiting as one of five artists, alongside leading abstract painters Tadashi Sugimata, Minoru Kawabata and Kumi Sugai, and the sculptor Ryokichi Mukai. And Aiko Miyawaki was celebrated in international exhibitions at, among other institutions, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

Most of them duly have one or two of their works in public collections. This does not mean they remained valued or were studied, however. Working with Nakajima and the curators Machiko Chiba and Yuka Egami, Nariai visited collections, archives and the families of the artists. “We discovered new works that had never been exhibited before,” he says. “Conversely, we also found many other women active in the 1950s and 60s, who frequently featured in magazines at the time, but we only know their names. We have no idea where they went, no contact details, and no clue where their works are.”

Unknown, unseen

The show travels to Momat from the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art. It was only when descendants of the painter Kazuko Enomoto encountered her works there (she has three works in public collections and a few more in private holdings) that the curators learned she had died in 2019, leaving behind a body of work hitherto unseen. That suggests there is more to be discovered and more research to be done—a hopefulness that resonates with the buoyancy of the works themselves.

Hideko Fukushima’s White Noise (1959) © the artist; courtesy Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts

In the 1950s and 60s, Kusama was working intensely using tiny marks and Fukushima using stamps; while Miyawaki was interested in intangible phenomena, Kinuko in weightlessness, and Tanaka in the potential of multicoloured lightbulbs. “Each experimented with expressly non-action methods,” Nariai says. “So many of the works are akarui,” he adds, a term that translates as bright, cheerful and enlightened. An electric show of power and self-belief, then, still waiting to be explored.

• Anti-Action: Artist-Women’s Challenges and Responses in Post-war Japan, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 16 December-8 February 2026