Marking its 40th anniversary, the 17th Bienal de Cuenca, titled The Game, opened on 24 October. Its inauguration coincided with the Art Basel Paris fair on the other side of the Atlantic, but the biennial offers a timely counterpoint. Specifically, it highlights artists and curators from the Global South, foregrounding the region’s social and political concerns over market priorities.

Set in Cuenca—one of Ecuador’s largest cities, whose centre is a Unesco World Heritage Site—the Bienal de Cuenca unfolds more than 2,000 metres above sea level amid the El Cajas mountain range. Established in 1987, the biennial remains the country’s leading international art event. It is funded by the municipality of Cuenca, which allocates $500,000 per edition, about a third of which covers operations and staff.

In 2023, the city’s mayor appointed Hernán Pacurucu as executive director of the Cuenca Biennial Foundation. Under his leadership, initiatives such as the Open Doors programme and Art Kiosk have expanded public access, circulating art nationwide and offering educational activities for children and school groups.

Ecuador has a dynamic cultural landscape, but its contemporary-art scene remains largely unknown internationally and seldom receives global coverage. New initiatives such as Guayaquil’s forthcoming Eacheve Foundation museum (opening in autumn 2026) and Quito Design Week are beginning to raise its profile beyond the region.

Yet this renewed cultural energy unfolds against a backdrop of political volatility. The Bienal de Cuenca arrived this year on the heels of the latest political uprising by the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador, which was triggered by the end of diesel subsidies and the government’s extractive agenda. In response to the unrest, president Daniel Noboa imposed a state of emergency in several provinces, restricting public gatherings and movement. The protests ended on 22 October, just two days before the biennial’s inauguration.

Carmen Vicente’s Infinite Steps Courtesy Bienal de Cuenca

Despite the tense national climate, the Bienal de Cuenca kicked off with an ambitious curatorial model featuring 17 prominent international curators. Each curator selected three artists—at least one of whom hails from Ecuador. Works by 51 artists are displayed across multiple venues, including museums, gardens, the airport, colonial convents and municipal galleries.

As political tensions subsided, the biennial opened with a ceremony that underscored the event’s commitment to Indigenous knowledge and spiritual reflection. The Chacruna offering, an Andean ritual honouring Pachamama (Mother Earth), was led by the Ecuadorian artist and curandera (medicine woman) Carmen Vicente. Her installation, curated by Amy Rosenblum Martín, won this year’s acquisition prize.

Vicente’s Infinite Steps is a deeply personal installation that confronts the devastation wrought by Covid-19 in Ecuador, one of the earliest epicentres of the pandemic in Latin America. The solemn work is comprised of walking sticks mounted on stone bases, each anchored by a single shoe. The handles are wrapped with multicoloured, doll-like figurines affixed to metal spoons, forming a silent procession of human figures.

“I started with a few pairs of shoes that were given to me by four family members who died during the pandemic,” Vicente tells The Art Newspaper. “And from there, more started to join in.” With Indigenous communities facing nearly four times the excess death rate of the general population during the pandemic, the artist transformed private mourning into a collective memorial.

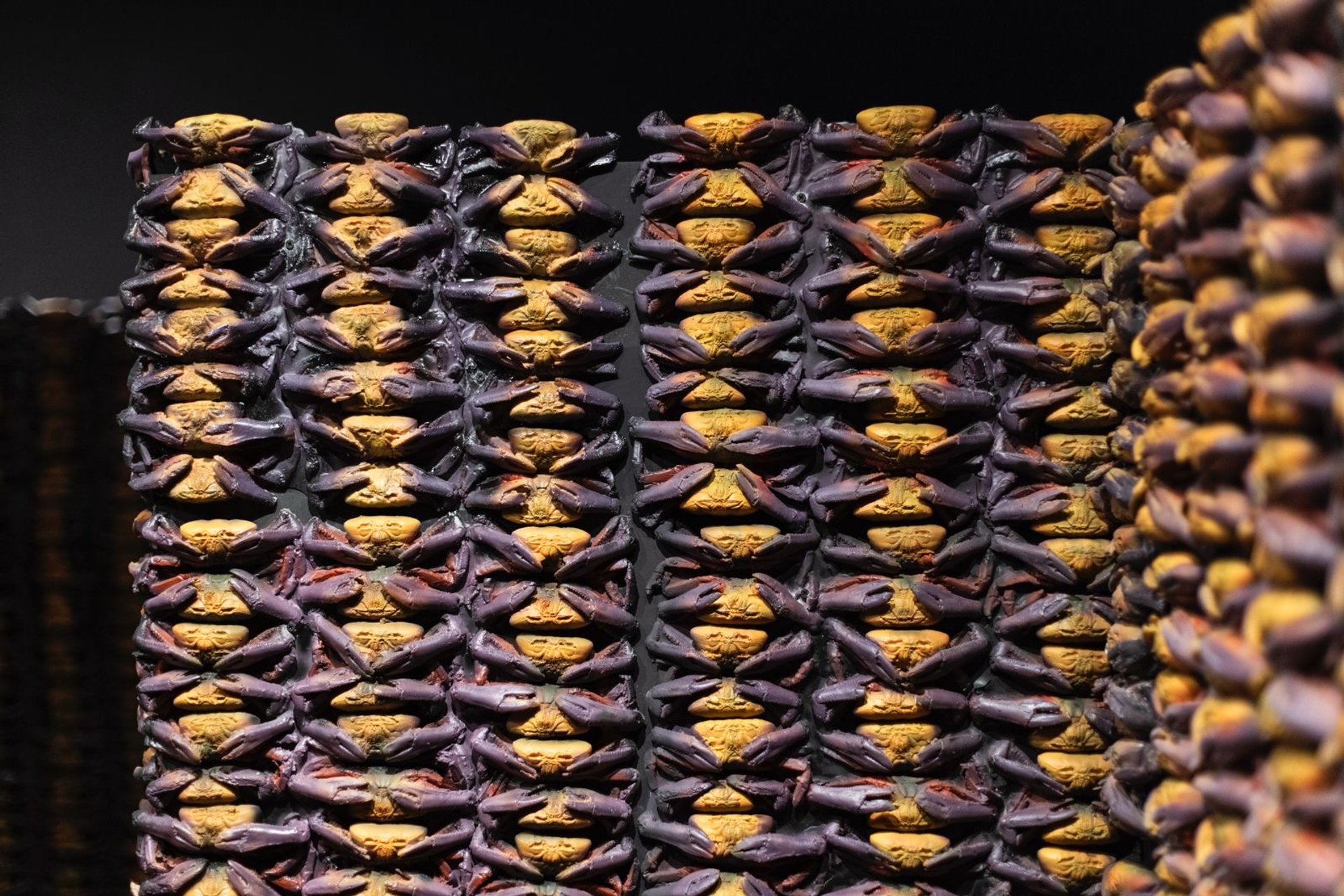

Close-up of Darwin Guerrero’s project at Bienal de Cuenca Courtesy Bienal de Cuenca

The organisers of The Game invited its curators to be active participants and consider play as a critical tool, resulting in projects that varied widely in tone and execution. The curators Gerardo Mosquera (from Cuba), Virginia Roy (Spain and Mexico) and Justo Pastor Mellado (Chile) delivered some of the biennial’s strongest and most focused presentations, engaging directly with social, political and psychological issues.

Mosquera received the award for Best Curatorial Team for his exhibition La Noche Bella no Deja Dormir (The Beautiful Night Keeps Me Awake), which features works by the artists Sandra Cinto, Rember Yahuarcani and Christian Proaño. The show explores death and the night as sites of reflection and revelation through large-scale painting, sound and literature. The presentation honours the Cuban national hero and writer José Martí while reasserting human connection over capitalism’s focus on individualism and hyperproductivity.

While Mosquera’s poetic exhibition emphasises reflection, Roy approached The Game through active engagement, creating a space for autonomy and negotiation while critiquing institutional control. Roy’s presentation, lo lúdico como potencia política (play as a political force), invites viewers to navigate a painstakingly made labyrinth of 26,000 resin-cast crabs constructed by the Ecuadorian artist Darwin Guerrero.

Also featured is a video by the Belgian artist Francis Alÿs, filmed in Ecuador’s Selva Alegre as part of his long-running exploration of children’s games, and a series of charcoal drawings embroidered in silver thread by the Argentine artist Ana Gallardo with phrases written by sicarios (child assassins). “In a dark time when neoliberal hegemony is stalking the world and limiting spaces for negotiation and creation, art can—and does—play a fundamental role,” Roy says.

Teo Monsalve’s installation at Bienal de Cuenca is part of his ongoing Neotropical Futurism project Courtesy Bienal de Cuenca

The theme of “playing dead” is explored by the curator Justo Pastor Mellado and the artists Manuela Ribadeneira, Oswaldo Ruiz and Francisca Aninat in a presentation at the 16th-century Convento de las Conceptas. The London-based Ribadeneira guides the viewer through a sequence of spaces: a monastic cell, a walled garden and, finally, a mausoleum—encapsulating the idea of thresholds and liminal states of consciousness. Beneath their associations with purity and transcendence, the scent of garden lilies contains the same compound released by a decomposing body, linking the rigidity of cloistered life with the rituals of death.

Other notable installations include that of the Quito-based artist Pamela Suasti, who explores systems of power and surveillance in collaboration with the Dominican-born curator Ezequiel Taveras. Suasti received the Paris Prize, a three-month residency in France, for Archive of a Gesture—a project that incorporates salvaged office documents the artist describes as “discarded material, a record, something official, printed, stored for years in boxes and boxes, later abandoned and rendered obsolete, though once so important”. By hand-moulding crumpled documents with a closed fist, Suasti transforms bureaucratic waste into a tactile archive of defiance and resistance.

In contrast, the Ecuadorian artist Teo Monsalve and the Colombian curator Santiago Rueda look outward, adopting a futuristic science-fiction lens to explore mestizaje (cultural hybridity) across time. Monsalve’s multi-layered installation, part of his ongoing Neotropical Futurism project, looks at the shared mythology and ecology linking cultures from Mexico to the southern Amazon. Using regionally sourced copper, Monsalve shows how traditional materials and symbols retain meaning in the digital age, imagining exchange across the region as a continuum between the past, present and visionary futures.

While the overall quality of the work is strong at this year’s Bienal de Cuenca, the lack of organisation, absence of maps and outdated website make navigating it an actual “game” for visitors. For many artists, opening weekend was a missed opportunity to share their projects with influential curators, cut short as the 17 curators were taken to the city of Loja for a conference. Several artists said that, after a week of installation, they had hoped for more meaningful interactions; instead, the curators scarcely had time to see completed works in situ. Hopefully in the next edition both artists and attendees at the opening will be able to use the time for critical dialogue.

- Bienal de Cuenca: The Game, multiple locations in Cuenca, Ecuador, until 1 February 2026