In 1968, when Robert Crumb published Head Comix, the poet Allen Ginsberg called him a “supreme funny underground comic strip incarnation of the post-historic flower age”. Crumb sang the praises of LSD. If you did not take drugs, Crumb’s entropic scenes could make you feel as if you did. Countless businesses pirated his images all the way to the bank. Andy Warhol was probably jealous, but he died before Crumb started making money.

Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life by Dan Nadel, a curator and writer of comic art, reminds us how Crumb’s cartoons violated whatever taboos were out there. Puritans could not purge his comics of satire and sex. Nadel also tells a wrenching story of the family that produced this rare talent and his visions. Critics still fault Crumb, who was born in 1943, for glaring sexism and racism. Cartooning would never be the same.

Crumb’s family had a gothic weirdness: a stern US Marine father; a Catholic mother who bore a stepbrother’s child before marrying Crumb’s father; a brilliant house-bound brother, Charles, who got Robert into comics and killed himself aged 49. Meanwhile Robert’s super-thick glasses made adolescence lonely and set him up to not fit in.

Nadel piles on more details, such as the moment when Robert and Charles abandoned the Catholic Church, or Crumb’s first museum exhibition in Peoria, Illinois, which took grey images drawn in 1966 to the US heartland—one sold for $25. In an honest but tone-deaf declaration to the locals of Peoria, Crumb wrote: “My drawings are my personal attack on the absurd, sick, ridiculous world that we live in. I attempt to mildly shock you out of the euphoric life-process you are now being controlled by, and to pull you into my world so that I can take over your mind.”

Dark and dirty

Forgoing art school, Crumb worked at American Greetings, a greetings cards business, where he mastered a wholesome verisimilitude worthy of Norman Rockwell. As a satirist he drew dark and dirty characters—seething Middle American everymen, parents demanding incest, the bearded and robed con-man guru Mr Natural, wildly racist stereotypes, often “in the act”. Semi-contrite when reproached, Crumb said he drew an inner hell that is part of American culture. Printed on the cheapest paper and sold as comic books, his work lacked Pop art’s blasé nonchalance. It hit the gut a lot harder than a Warhol soup can.

By early 1966, according to Nadel, “Robert had summoned the language and discovered the vehicle for his long-simmering ideas about life, sex, race and civilisation.”

Crumb’s best-known creations sold, whether it was his Keep On Truckin’ images, the Fritz the Cat comic strip or the celebrated Cheap Thrills 1968 album cover for Big Brother and the Holding Company. Yet he still struggled. Many of his comics reached readers through distributors of pornography bearing titles such as Fug, Snatch and Big Ass. Were the moralists right after all? The lawyers who sued the “legitimate” businesses that stole his images kept him alive.

By the late 1960s, Crumb’s signature cosmology included gaggles of figures crammed into a comic’s panels—hence the comparison to the early-Modern visions of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Breughel the Elder. Bawdy scenes with shrivelled men and massive women evoke the 18th-century literary satires of Jonathan Swift. Mad magazine was a crucial influence.

Crumb lived the sexual revolution of his moment. His two marriages were anything but monogamous. In his signature honesty, sex was as raw as everything else that he drew, which brought him under attack. On that messy subject, Nadel sees Crumb as an observer who draws and defends his stories about things that he hates, insisting that he is showing the world as he sees it. To his credit, Crumb admits that the world in question includes him too.

“Stereotypes are how all white people see the Black population,” writes Nadel, encapsulating Crumb’s perspective. “It is, at the very least, the vision of race with which he was indoctrinated as a child … part of the American vernacular.” “Robert himself,” Nadel concludes, “was the thing he hated.”

Cherished isolation

Crumb left for France in the 1980s—not speaking the language kept the crowds away. The comics-obsessed French still revere him. Starting off in Paris, Crumb and second wife Aline Kominsky settled in Sauve in the enchanting Cévennes region. The town’s very name echoes the French word for “save”. It suits the octogenarian cartoonist, to a point. He still feels American.

Wealth to share came late to the man who, for decades, traded his art for vinyl records

Now his work sells as art. The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art in Los Angeles paid $2.9m for original drawings from The Book of Genesis Illustrated by R. Crumb. Exhibited at multiple museums and the mega-powered David Zwirner Gallery, it was, to Crumb’s surprise, by far his best-selling work, with the gallery selling Genesis sketch books for $900,000. The cash funded Crumb’s expatriate life and supported family members. Wealth to share came late to the man who, for decades, traded his art for vinyl records.

Crumb’s public retort was that he did Genesis for the money, as an “illustrator”. Nadel insists that it is no less than “Robert’s final grafting of his consciousness—the mystic, the lowbrow, the erotic, the ironic—onto Western civilisation”.

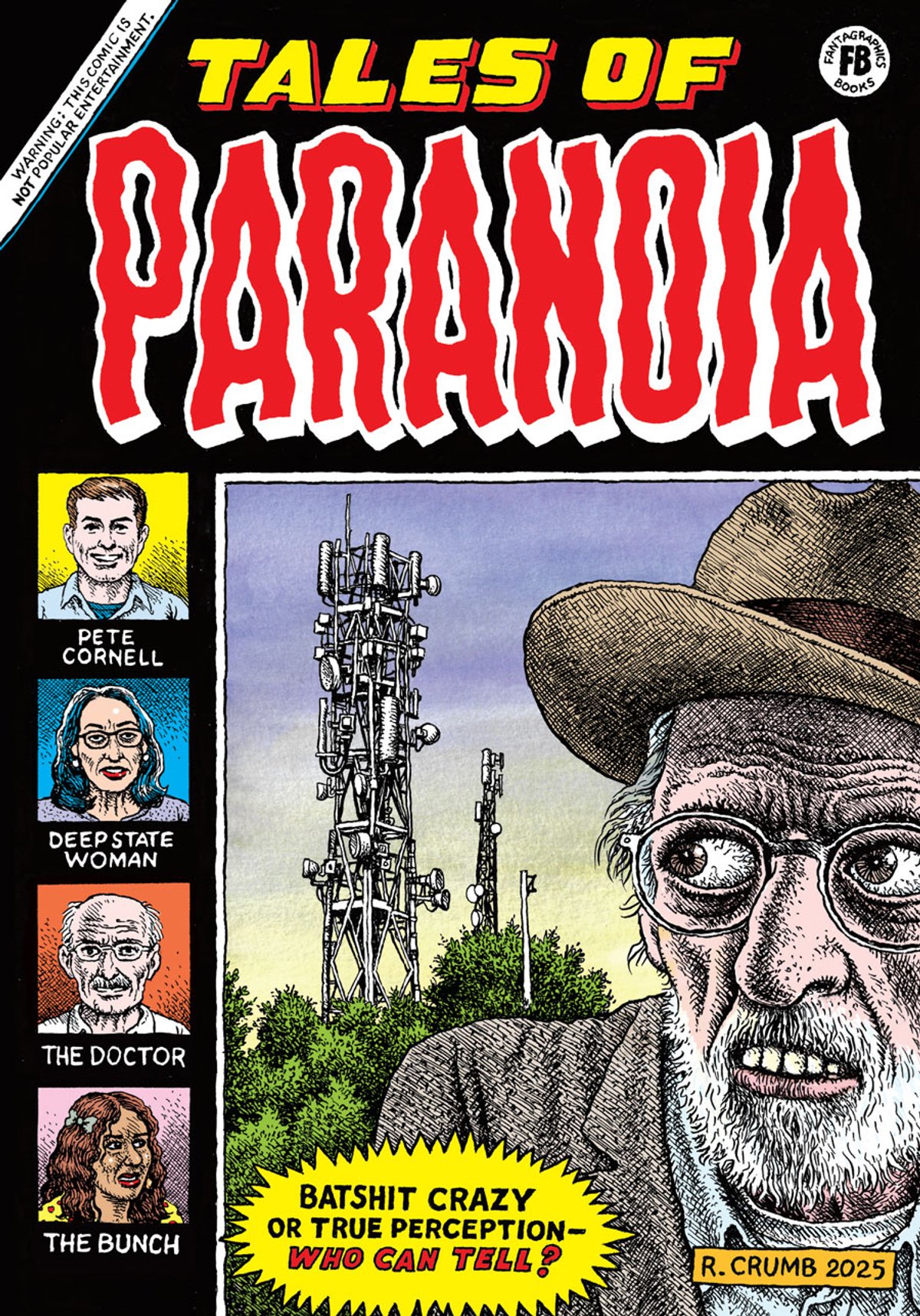

Not so fast. Crumb is now among dozens of artists that the Whitney Museum in New York seeks to contextualise, or recontextualise, in the exhibition Sixties Surreal (until 19 January 2026), co-curated by Nadel. Is the man who thought he was making comics now a Surrealist? And in November, Zwirner displayed R. Crumb: Tales of Paranoia, his first solo comic in more than 20 years—an insistent, feverish self-portrait denouncing grand conspiracies in small print. It has been published as a comic by Fantagraphics. The reader must once again distinguish between Crumb the artist and Crumb the character—if, that is, there is a difference.

• Dan Nadel, Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life, Scribner, 480pp, 83 illustrations,

$35/£25 (hb), published 22 May

• David D’Arcy is a regular contributor to The Art Newspaper