The American writer Mark Twain was fond of the saying, “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damn lies and statistics.” When we hear statistics supposedly proving that the arts are good for our health, how do we know they are not unrepresentative numbers being quoted by the arts sector desperately pleading its case for more money?

Daisy Fancourt, 35, is professor of psychobiology and epidemiology (investigating the causes and spread of diseases) at University College London, and has raised the study of the effects of the arts on health to a level of statistical credibility that might convince even Mark Twain.

To be valid, statistics need to be based on a large enough sample to be representative of the selected study group, adjusted to take account of potentially distorting factors, and with the data gathered over a long enough period to show tendencies, not just occasional responses to situations.

The genius of her approach is that she realised there was a goldmine of just such solid data waiting to be interrogated in the so-called cohort studies involving tens of thousands of people and extending over decades, which have been conducted in the UK as a function of epidemiological studies. They contain detailed medical information, including psychological data, as well as assessments of peoples’ education, economic status, work and lifestyle. Fancourt discovered that seven of the biggest had also included questions about peoples’ engagement in the arts, such as how often they had played an instrument, visited a museum, danced, read poetry, performed in a play, painted a picture and so on, so she had her source material ready-made for her.

The first of her analyses drew on the English Longitudinal Study of Aging, begun in 2002 and still ongoing, which invited 12,099 people living in England and born before 1952 to answer detailed questionnaires and undergo medical tests every two years.

Fancourt identified the 2,148 who had no recent history of depression, and, with the information that these people gave biennially, she discovered that the ones who engaged in cultural activities developed depression at half the rate of those who did not. She then identified anyone who enjoyed a higher income, a more sociable life or better health, but even taking account of these potentially confounding factors, the result remained convincing: 35% of the culturally inactive group developed depression over the following decade, but only 23% of the culturally active.

She published this result in 2019. Since then, she has looked at data relating to millions of people, in studies of her own and others conducted from Finland to China, and the conclusion is a certainty. The arts are good for health, both physical and mental. Apart from warding off depression and helping you live longer, they can lower blood pressure, calm panic attacks and post-traumatic stress, reduce the need for heavy anaesthesia, and revive partial activity in a mind closed down by dementia.

The effects on the body

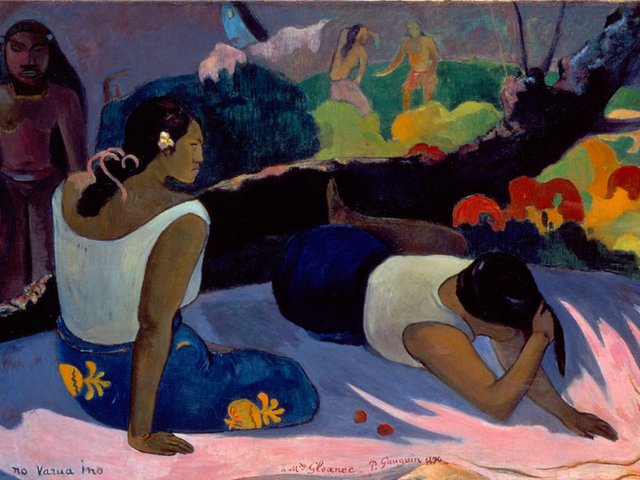

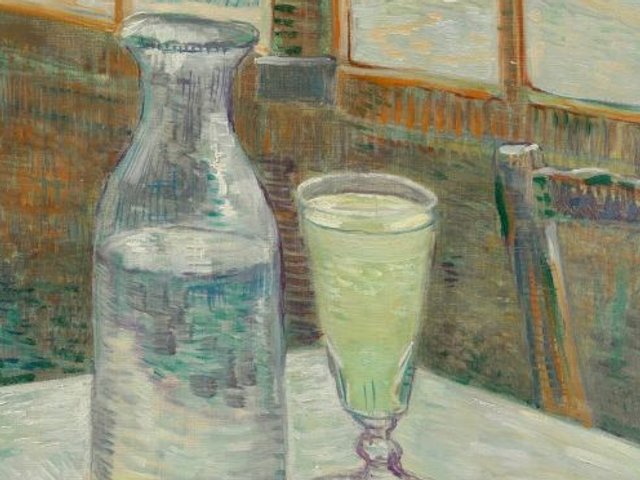

What does engaging with art do to the body? This has been widely studied using brain imaging, MRI and PET scans, saliva tests and so on, to give just two effects. Damaging cortisol levels caused by stress are reduced, while the level of dopamine rises, improving the memory. A small experiment last year by King’s College London and financed by the Art Fund monitored the heart rate, temperatures and saliva of 50 volunteers who looked at paintings by Van Gogh and Gauguin. Their beneficial physical reactions were perceptibly greater when they looked at the originals than when they looked at reproductions in a non-gallery environment. (But perhaps this comparison did not need scientific testing, because we are highly suggestible creatures and context influences us very much, as any luxury salesperson will tell you.)

Professer Daisy Fancourt has studied the effects of art on health Courtesy Daisy Fancourt

Fancourt’s Art Cure: The Science of How the Arts Transform Our Health will be published by Cornerstone Press this month and it ends with recommendations of how we need to experience art. Above all, we must engage with it: listen properly to a piece of music; take part in a play; draw or paint; stand in front of a picture long enough to see it properly (and put that iPhone away). She has reservations about how beneficial watching the arts on screen is and perhaps her next step could be to settle that very relevant question.

She points out the irony of public money for the arts diminishing year on year in the UK and other countries, while the evidence is becoming overwhelming that they could make huge savings to health budgets.

The World Health Organisation (WHO), which has been right behind the study of art in health since 2019, has made her a director of its Collaborating Centre for Arts and Health. In September the need for governments to take the matter seriously was the theme of the WHO’s Healing Arts Week in New York, at venues including the Guggenheim Museum, run by the Jameel Arts and Health Lab in conjunction with the United Nations’ annual General Assembly.