Dozens of graffiti messages have been discovered at Pompeii, shedding light on the violence and intimacy of everyday life—as well as its cosmopolitan social fabric.

Archaeologists have analysed 79 new scribblings carved into the plaster wall of a corridor. The space was once a passageway between two theatres, in which chatting residents socialised, took shelter from the heat and occasionally participated in less innocent pastimes.

The passageway was first excavated in 1794, and around 200 inscriptions have previously been found along its 27m length. Many additional scribblings, however, have until now been too faint to read. It has taken fresh research using state-of-the-art digital technology to unlock their often-salacious contents.

The Corridoio Teatri, where the graffiti was analysed

Pompeii Archaeological Park

One inscription indicates that Tychè, a sex worker, was paid to have sex ad locum (“in this place”) with three men.

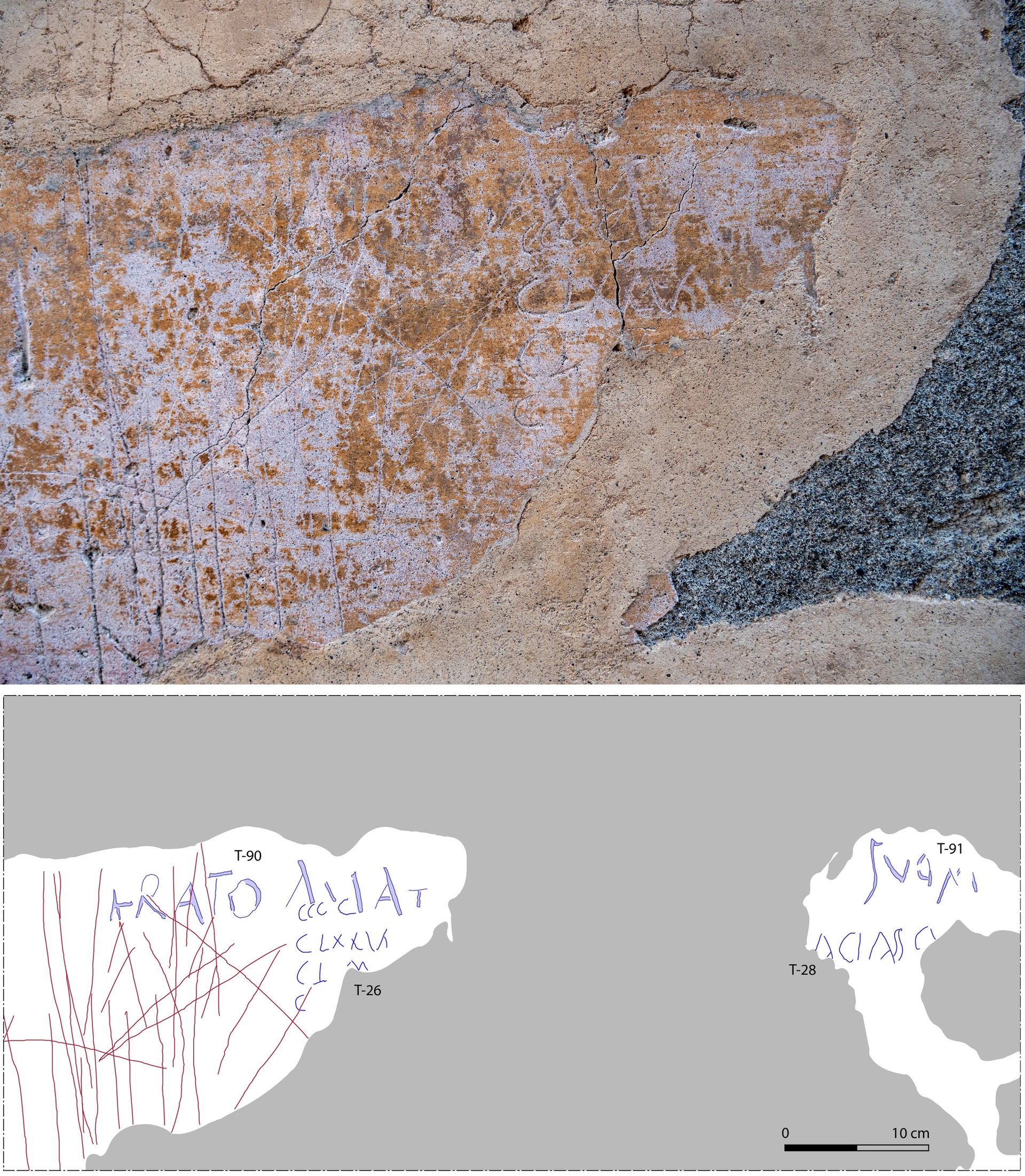

Others reference less physical forms of passion. "I am in a hurry. Farewell, my Sava, make sure you love me!", one message reads. “Erato loves…”, states another partially readable inscription.

"It’s a kind of notice board… where people left messages, history, greetings, insults, drawings and much more,” says Gabriel Zuchtriegel, the park's director, in a video circulated by the park.

Graffiti including the phrase “Erato amat“, or “Erato loves…”, with a clarifying illustration below

Pompeii Archaelogical Park

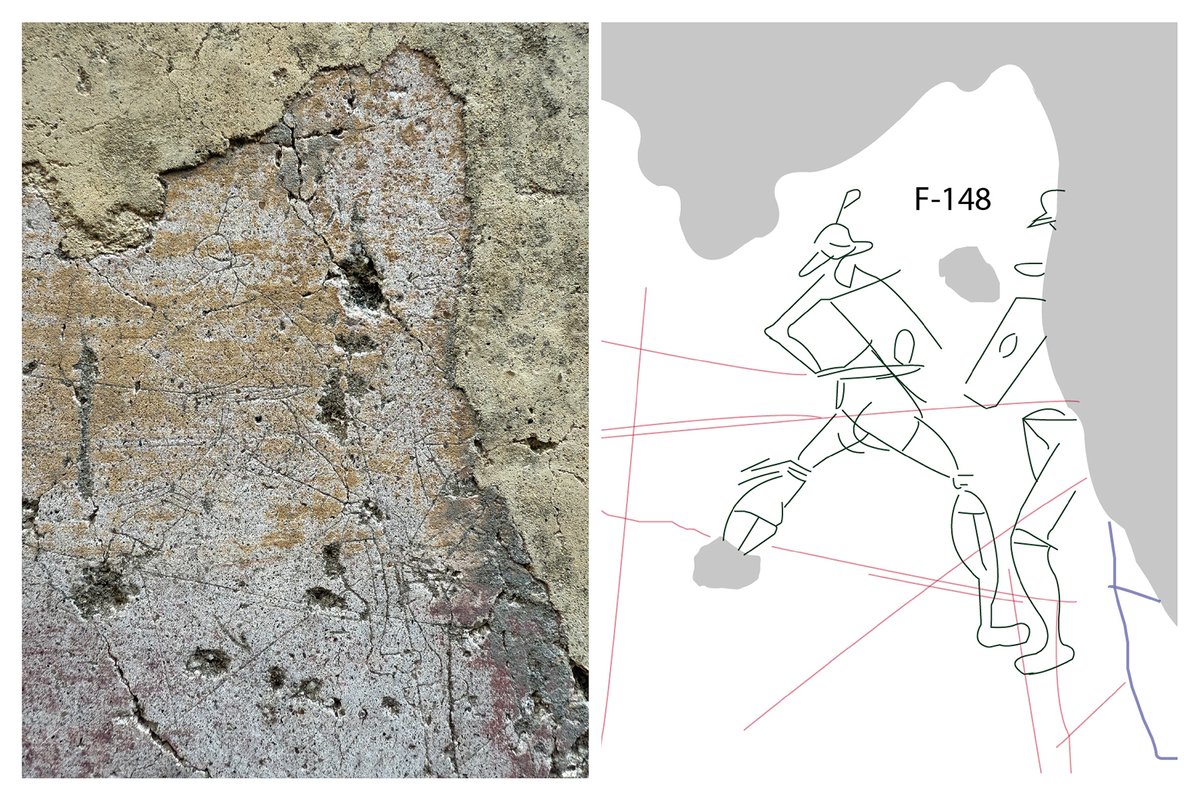

The discoveries also include a faint sketch of two fighting gladiators, one of whom leans backwards in a feint or parry pose while holding his pointed sword horizontally in a bent arm.

One message—“Tertiani lived here”—may refer to soldiers from a Gallic legion that went by that name, and were stationed in Pompeii during the civil war of 69-70 AD, researchers suggest. Inscribed Safaitic, or proto-Arabic, names indicate some of the soldiers may have been from the Arabian desert.

The new inscriptions were recorded using Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), a technique that involves synthesising multiple digital images to create one hyper-realistic image. The process reveals details the naked eye cannot see.

Together with photogrammetry and inscription metadata, the RTI images will form the basis of a new online 3D platform allowing scholars to visualise the inscriptions and collaborate on annotating them.

The platform is planned to go live this year. Following an initial research phase, it will be accessible by the general public.

“Technology is the key that unlocks new rooms in the ancient world,” Zuchtriegel said. “Only the use of technology can guarantee a future for all these memories of life in Pompeii.”

The director added that there were 10,000 inscriptions across the Pompeii site. He called it “an immense heritage”.

The archaeological park plans to build a cover over the corridor to better protect the plaster and graffiti.