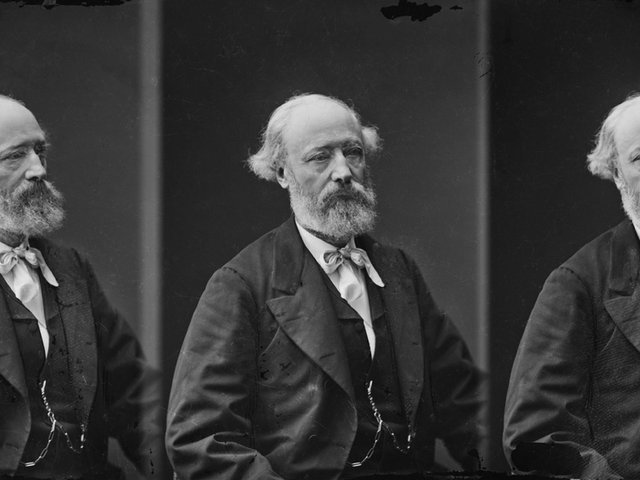

In the US, Frank Lloyd Wright is as close to a household name as any architect in the history of the country. But precious few Americans are familiar with Wright’s 19th-century predecessor and inspiration, the French architect Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1814-79). That may change a little this month, when the Bard Graduate Center in New York opens the first major show about him in the US.

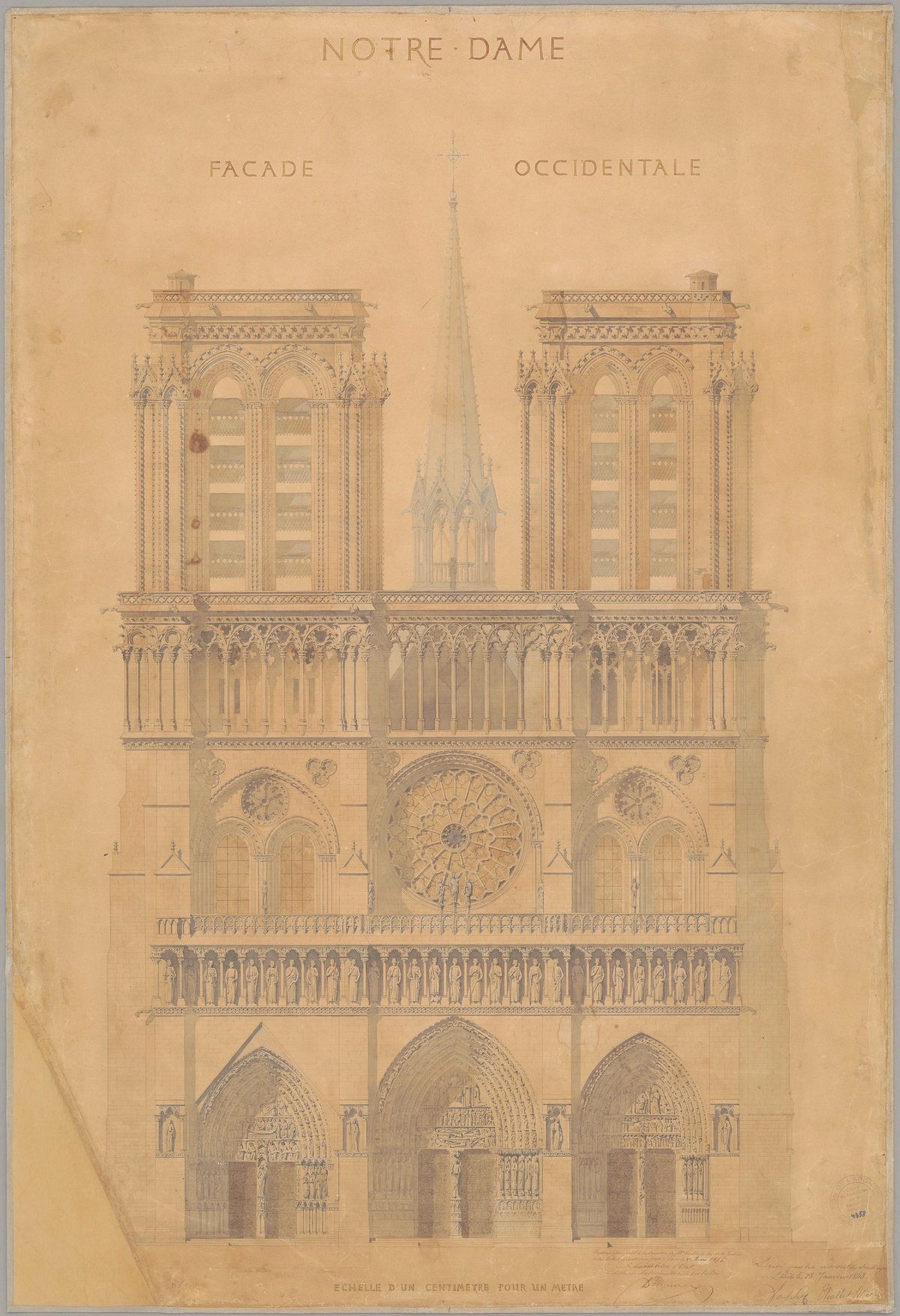

A fine and applied arts polymath, as well as a mystically inclined visionary, Viollet-le-Duc, a native Parisian from a family of artists and high-ranking civil servants, is celebrated in France for overseeing the preservation and restoration of some of the country’s most important Medieval structures and monuments, including the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris. But he was also a theoretician and a gadfly, and had an immense impact, not only on the direction of architecture, but on how the present can and should regard the past. The Bard exhibition will show more than 150 of his drawings to gain insight into his fertile imagination and industrious working methods.

Relying on a number of French sources, especially the archives of the Médiathèque du patrimoine et de la photographie, Viollet-le-Duc: Drawing Worlds will span five decades, starting with his fanciful teenage depictions of French harbours and culminating in late ruminations on Medieval weaponry.

The curators have had a wealth of material to choose from—the Médiathèque alone holds some 20,000 of his drawings. Viollet-le-Duc was a “compulsive” draughtsman, explains Martin Bressani, an emeritus professor of architecture at McGill University in Montreal. The Canadian is co-curating the show with Barry Bergdoll, an art history professor at Columbia University.

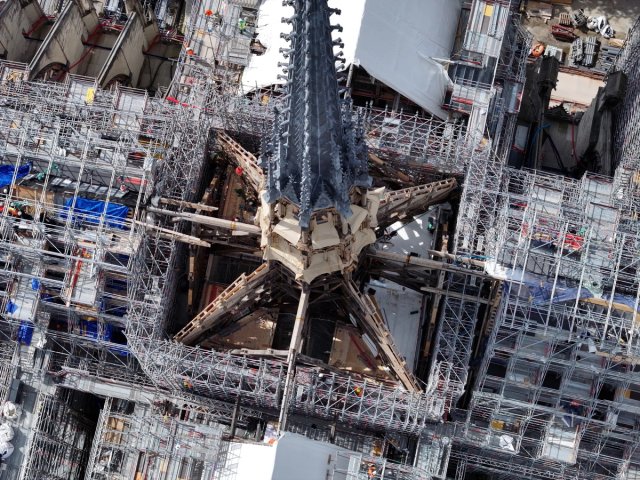

Viollet-le-Duc is credited with both reviving and reinventing Notre-Dame in the 1850s, when he helped oversee an altering restoration of the cathedral that included designing and installing a highly distinctive spire. His towering oak spire, while meant to replace a more modest Medieval version that had been dismantled at the end of the 18th century, was the Frenchman’s meditation on an idealised past rather than a recreation of what had once been. This dynamic approach to historic preservation—and, indeed, to history itself—is what so inspired Wright and others.

Following the near destruction of the cathedral in a 2019 fire, Viollet-le-Duc’s version was, somewhat ironically, faithfully remade and replaced. And the reopening of Notre-Dame last year is an occasion for the show, Bressani says.

A proto-Modernist?

Fittingly, the exhibition is rich in exquisite plans and interpretations of the cathedral, which mesmerisingly merge the Middle Ages with a kind of proto-

Modernist—or least technically astute—eye. An 1857 presentation drawing, showing the spire in elaborate isolation, somehow anticipates the Eiffel Tower.

Viollet-le-Duc’s interventionist approach has had its critics. He was “actually vilified in the early 20th century,” Bressani says. And some of his drawings vividly illustrate how he viewed preservation as an essentially creative act.

Carcassonne, the fortified Medieval city in the south of France, was restored by Viollet-le-Duc at around the same time he was working on Notre-Dame, and an 1853 ink and watercolour drawing bizarrely captures the fortress in both its original and restored states in a single image. The original, hovering at the bottom, looks like a vanquished vision of the reinvented town.

Making the silent stones speak: Viollet-le-Duc’s 1840 drawing of the antique theatre at Taormina in Sicily incorporated the performance of a classical Greek drama © Grand Palais

One surprising aspect of the show, even for scholars familiar with his architectural works, will be how Viollet-le-Duc turned his revising instincts on the natural world. Near the end of his life, he made trips up into the French Alps, and a pair of related drawings contrast a glacier ridge near Chamonix, as it existed in August 1874 during his visit, with a vision of it “restored” in an imaginary Ice Age.

This instinct to remake the past predates his working life as an important architect in the France of the Second Empire. An 1840 colour drawing, done in response to a visit to Sicily, fully restores Taormina’s ancient Greek theatre to a flourishing classical state, replete with a play in mid-performance.

Viollet-le-Duc had a dark and pseudo-scientific side, Bressani concedes. Drawn to the racialist theories of his friend, Arthur de Gobineau, who is credited with first expounding the idea of a superior “Aryan” race, Viollet-le-Duc was also fascinated by military prowess, which found expression in the precise and menacing warfare drawings that help wind down the show.

By way of demonstrating his eccentricity, the curators have included his custom-built desk—a curious-looking contraption that seems to combine a working surface with a bookcase and some drawers, creating a near-organic object that only an animator might otherwise attempt. Viollet-le-Duc liked to sit in it, Bressani says, “while dressed in a Medieval robe”.

• Viollet-le-Duc: Drawing Worlds, Bard Graduate Center, New York, 28 January-24 May