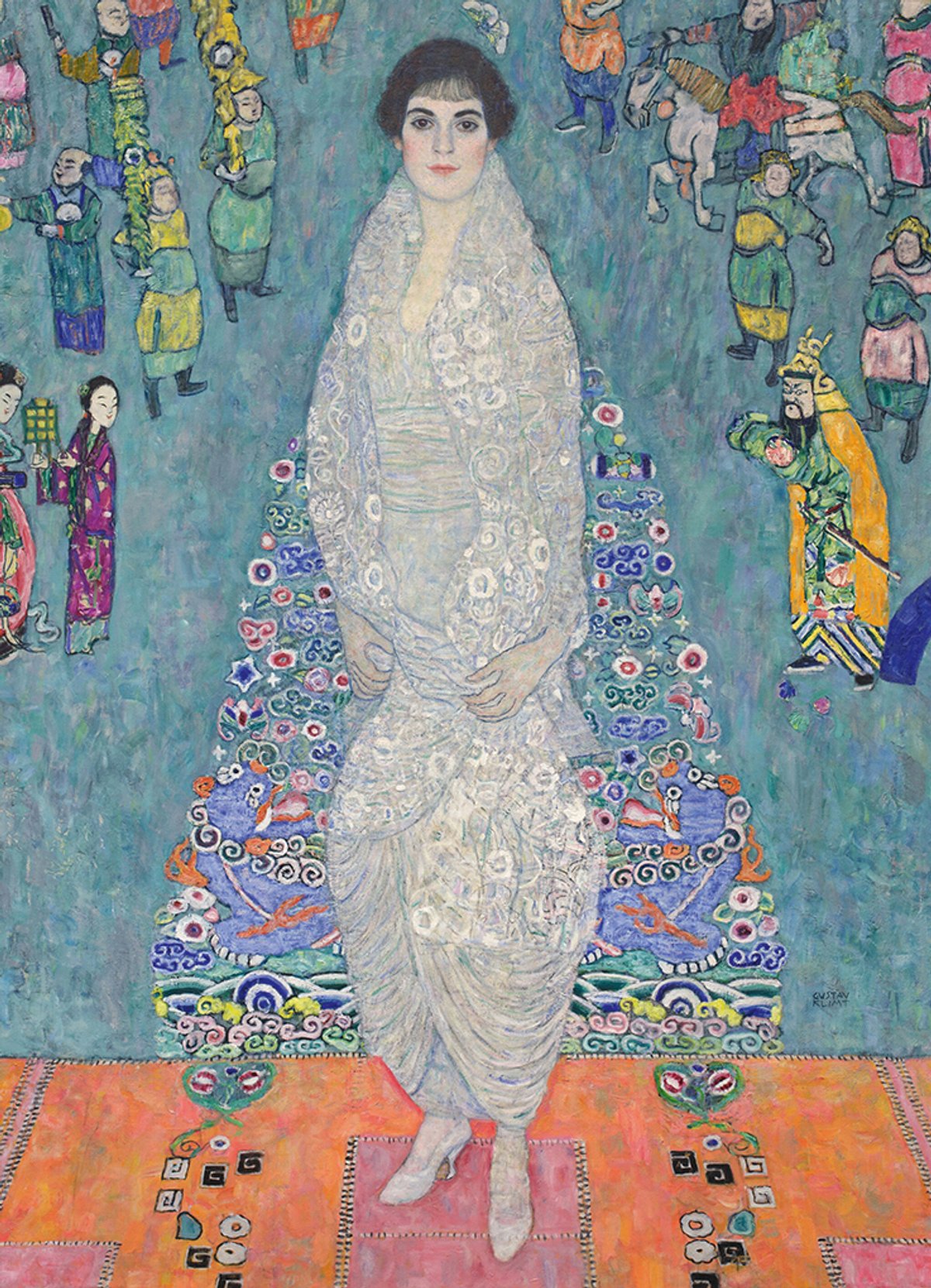

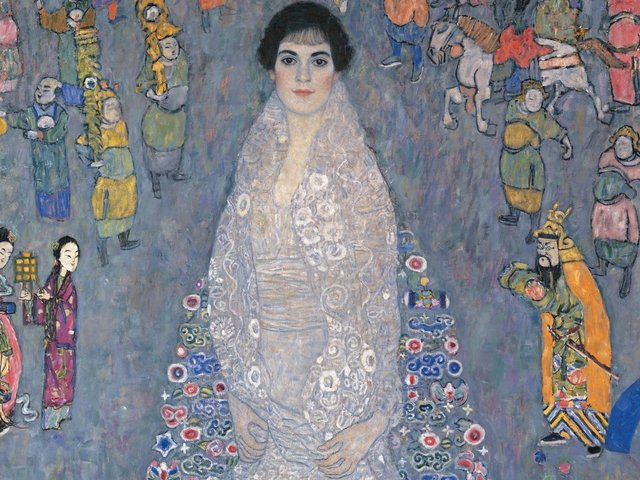

When Gustav Klimt’s Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer (portrait of Elisabeth Lederer, 1914-16) sold at Sotheby’s auction of the collection of Leonard Lauder in New York in November for $205m ($236.4m with fees), many were flabbergasted. But not the Klimt experts.

“It is the last great full-scale Klimt painting, and when you’re talking about such trophy pictures, then it’s really a question of who’s going to blink first,” says the Klimt expert and dealer Richard Nagy. “People that are interested in these trophies, they’ve made so much money in the last five or ten years that I don’t see that whether they spend $150m or $200m changes much for them. What I find fascinating is, why do they stop [bidding]?”

As Jane Kallir, the president of the Kallir Research Institute, says, the top strata of the market is incredibly rarefied: “There are so few people who can collect at that level; there’s always been a deep divide between Klimt’s millions of fans and what collectors actually can afford to buy.”

Last hurrah of the Belle Époque

Klimt has a magnetic hold over people. His works are supremely decorative, of course, but, as Nagy says, “he’s also really the last hurrah of the Belle Époque before the First World War ends it all. It’s the last vestiges of symbolism and the new world coming.”

Helena Newman, Sotheby’s European chairman and chairman of Impressionist and modern art worldwide, was closely involved in the Lederer portrait sale and in that of the last significant Klimt to come to auction, Lady with a Fan (1917), which sold for £85.3m (with fees) at Sotheby’s in London in 2023, then a European auction record for Klimt. Newman says that the particular context of the Lederer painting is important. “This is the daughter of Klimt’s most important patron, so it links you directly with what was going on in Viennese society at that moment, that sense of Vienna as a cultural crossroads, as epitomised in this painting,” she says. “We know that Klimt went to Ravenna in the early 1900s and he saw the mosaics there, so he’s drawing on all these influences, from Byzantine to Asian to Modern European.”

Owned by the Lederers, Klimt’s greatest patrons, until their collection was stolen by the Nazis during the Second World War, Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer was then restituted to Elisabeth’s brother (and only surviving relative), Erich, in 1948. He sold it in 1983 to the Serge Sabarsky Gallery in New York, which in turn sold it to the cosmetics billionaire Leonard Lauder in 1985. Newman says that the other Klimt paintings from the Lederer collection—apart from the Whistler-esque portrait of Elisabeth’s mother Serena Pulitzer Lederer (1899), which now hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art—were burnt in the 1945 fire at Schloss Immendorf, the castle where they had been stored during the Second World War after they were confiscated by the Nazis as assets of a Jewish family.

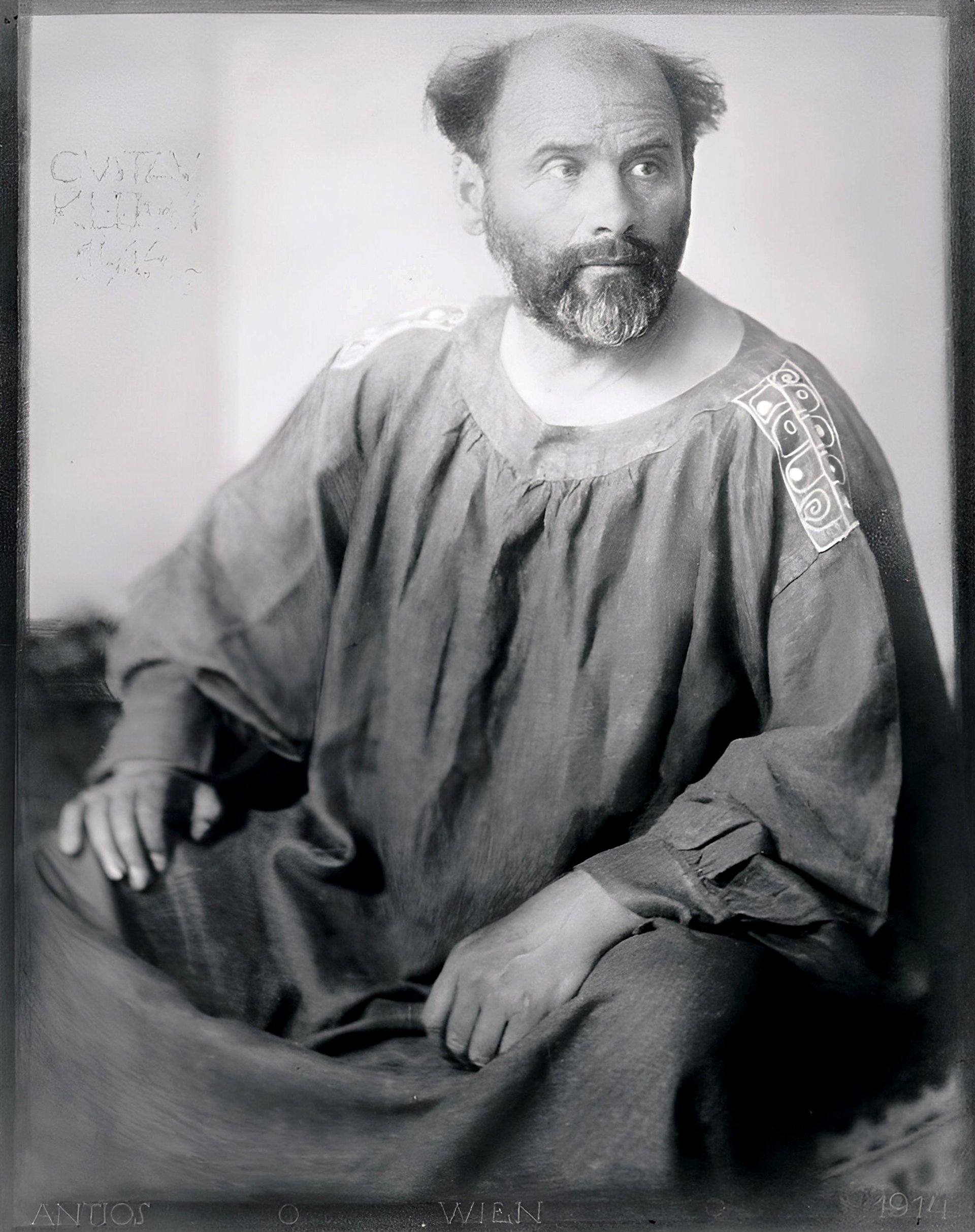

Photo of Gustav Klimt taken in 1914 by photographer Josef Anton Trčka

Private deals

As has been well noted, Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer is the last great, full-scale commissioned portrait by Klimt not in a museum, aside from Adele Bloch Bauer II (1912), which was reportedly sold privately by Oprah Winfrey to an anonymous Chinese collector for around $150m in 2017. Though not a commissioned work, there is also Water Serpents II (1904-06/07), which was embroiled in the long-running feud between the dealer Yves Bouvier and the Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev. The latter’s company, Accent Delight, bought the painting from the former for $183.8m in 2012—a figure Rybolovlev later argued was unreasonably high—before selling it privately to an Asian buyer for $170m in 2015, according to Bloomberg.

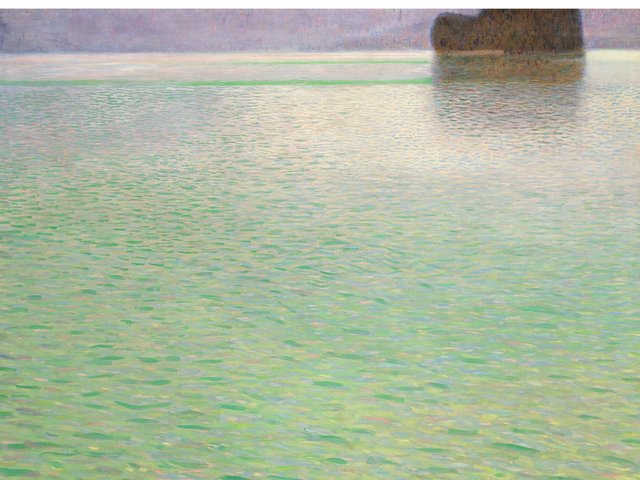

Such private deals lend precedent to the Lederer price, Nagy says. “The Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I [1907] that Ronald Lauder [Leonard’s brother] bought privately in 2006 was reported at $135m and there was the landscape sold at the Paul Allen sale for $104.6m,” he says, referring to Birch Forest (1903), sold in 2022 at Christie’s and now the third most expensive work by Klimt sold at auction. “So, I can see that people can extrapolate from those prices to arrive at this new level.”

Unique pictorial language

Such portraits of women and landscapes are among Klimt’s most popular works, says Tobias Natter, who was the director of the Leopold Museum in Vienna from 2011 to 2013, has curated Klimt exhibitions worldwide and is author of the 2012 catalogue raisonné published by Taschen. “The Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer is a fine example of this, not least because of its recognisability,” Natter says. “Klimt was able to create a unique pictorial language. In combining colour, ornamentation and eros he created a trademark and more than that.”

Natter adds that the major auction houses make “enormous efforts” to consign oils by Klimt, “often even to the limits of economic profitability [due to deals cut on fees]. But the marketing value is enormous.” Especially, Natter says, because they consistently perform: “They go into the auction with top estimates and constantly achieve even higher record results.”

As the large oils are few and far between, but hugely valuable when they do come up, annual auction sales values for Klimt’s work yo-yo dramatically. For instance, according to data from ArtTactic, in 2025 $342.5m worth of Klimt works were sold compared with just $399,606 in 2024, but $144.2m in 2023, largely due to Lady with a Fan.

Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss (Lovers) (1908), on permanent display at the Upper Belvedere, Vienna © Belvedere, Vienna

In short supply

The Lauders were early US collectors of Klimt’s work, with Ronald S. Lauder establishing the Neue Galerie in New York in 2001. The collector base now is truly global, Nagy says, with a handful of landscapes going to collectors in former Soviet countries after the fall of the Berlin Wall in the early 1990s, and the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art in Japan accumulating Viennese works by Klimt and Egon Schiele around 25 years ago.

On the supply side, Klimt’s paintings are extremely rare, a combination of the Schloss Immendorf fire and the fact that he did not paint many in the first place. “To put it somewhat exaggeratedly, Picasso painted more works in one year than Klimt did in his entire life,” Natter says, adding that only one early minor work has been added retrospectively to the 245 paintings listed in his 2012 catalogue raisonné.

As Klimt’s work was almost always originally owned by wealthy Viennese Jewish families, many (perhaps most) were looted by the Nazis or the subject of forced sales during the Second World War. “When important Klimt paintings have come onto the market in the last 20 years, it has mainly been through restitutions,” Natter says. “Each of these restitutions has caused a stir every time, with Klimt constantly being the talk of the town and appearing on every front page.”

Messy restitutions

But restitution cases, particularly when such valuable works are at stake, can get messy. Currently in the news is the controversy over Klimt’s painting, Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona (1897). This early painting depicts a West African man of the Osu people from modern-day Ghana whom Klimt encountered in a “human zoo” in Vienna in the late 19th century. It was exhibited by the Vienna-based gallery Wienerroither and Kohlbacher Gallery (W&K) at Tefaf Maastricht in March of last year, priced at around €15m. Before the Second World War it was thought to be owned by Ernestine Klein and her husband Felix, who fled Austria in 1938 when it was annexed by the Nazis.

The painting’s whereabouts thereafter are unknown but it appears to have been in Hungary until 2023, when it was brought into W&K’s gallery and identified. A restitution settlement was made with Klein’s heirs before the painting was shown in Maastricht but now the Hungarian authorities claim it was improperly exported and, in November, prosecutors in Vienna ordered the seizure of the painting from W&K on behalf of the Hungarians. The situation is ongoing.

Drawing conclusions

The recent Lauder sale at Sotheby’s also included two drawings by Klimt, both studies for Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1903-04), which sold for $520,700 and $482,600 respectively—several times their estimates and, Kallir says, way outperforming the general Klimt drawings market, probably thanks to the combined Bloch-Bauer and Lauder provenance. “They were interesting studies for Adele Bloch-Bauer, but they’re not exceptional drawings,” Nagy remarks.

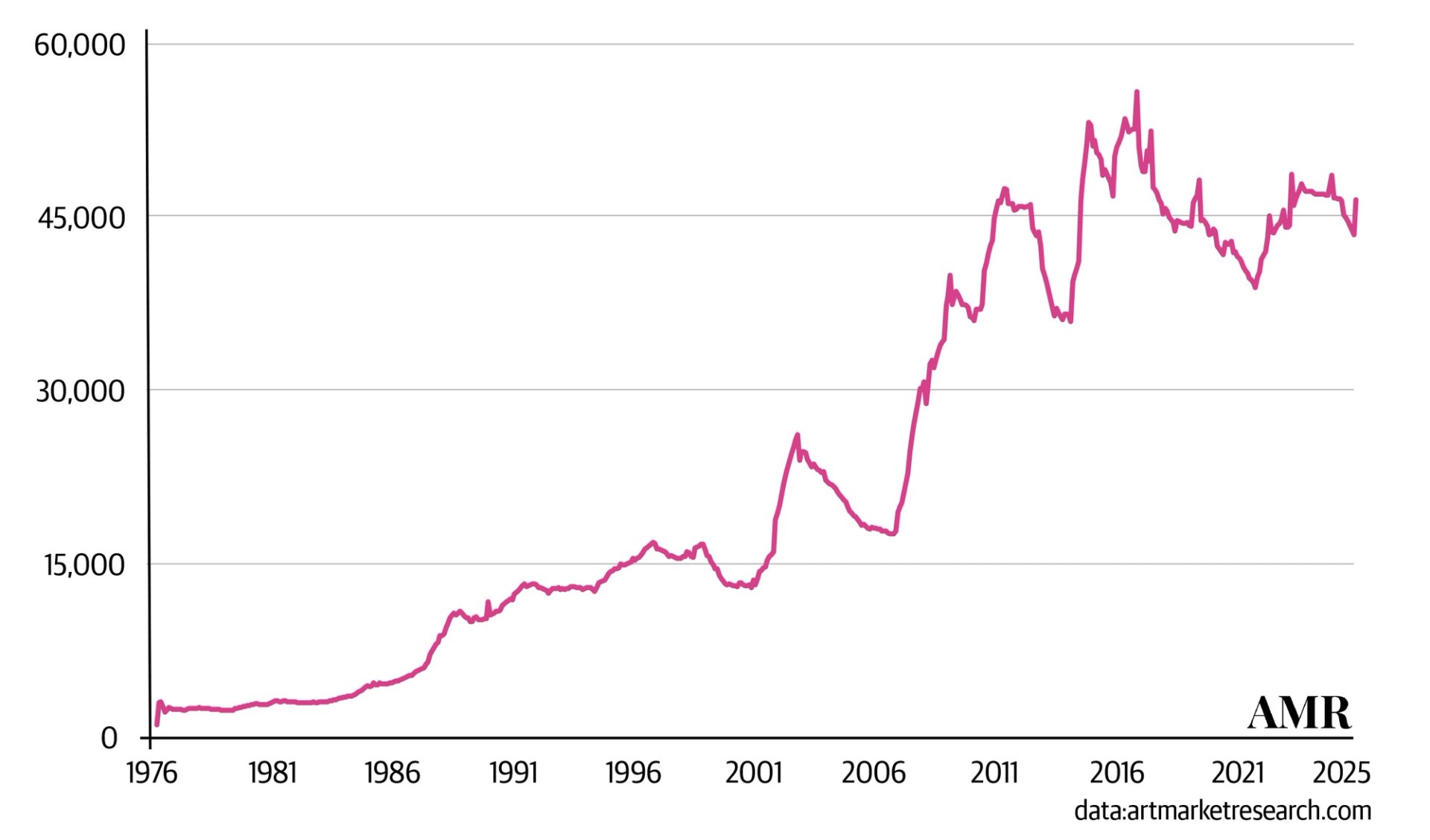

Although Klimt’s drawings are far more numerous than his paintings, their market lags significantly behind. The comparatively lower value and higher volume of drawings sold accounts for the perhaps surprisingly low median value of works sold shown in the graph (pictured below) using data from Art Market Research.

Half a century of Klimt sales (100% median), with prices (y-axis) in sterling

Katherine Hardy

While there is no authentication board for his painted body of work, Natter says, “it is different with his drawings. Klimt created drawings with great ease. There are over 4,000 of them.” Natter points out that some Klimt drawings were “relatively more expensive in the 1970s, when Klimt became internationally known” and experienced the beginning of his worldwide breakthrough, than they are today.

Nagy is starting to see “something of a knock-on effect” in terms of interest in the drawings thanks to the stratospheric painting prices. “I did a Klimt exhibition at Art Basel in Hong Kong in February, all works on paper, and it was very successful. I’m planning on doing another in London next October.”