The Art Newspaper:What elements in the drawing did you focus on?

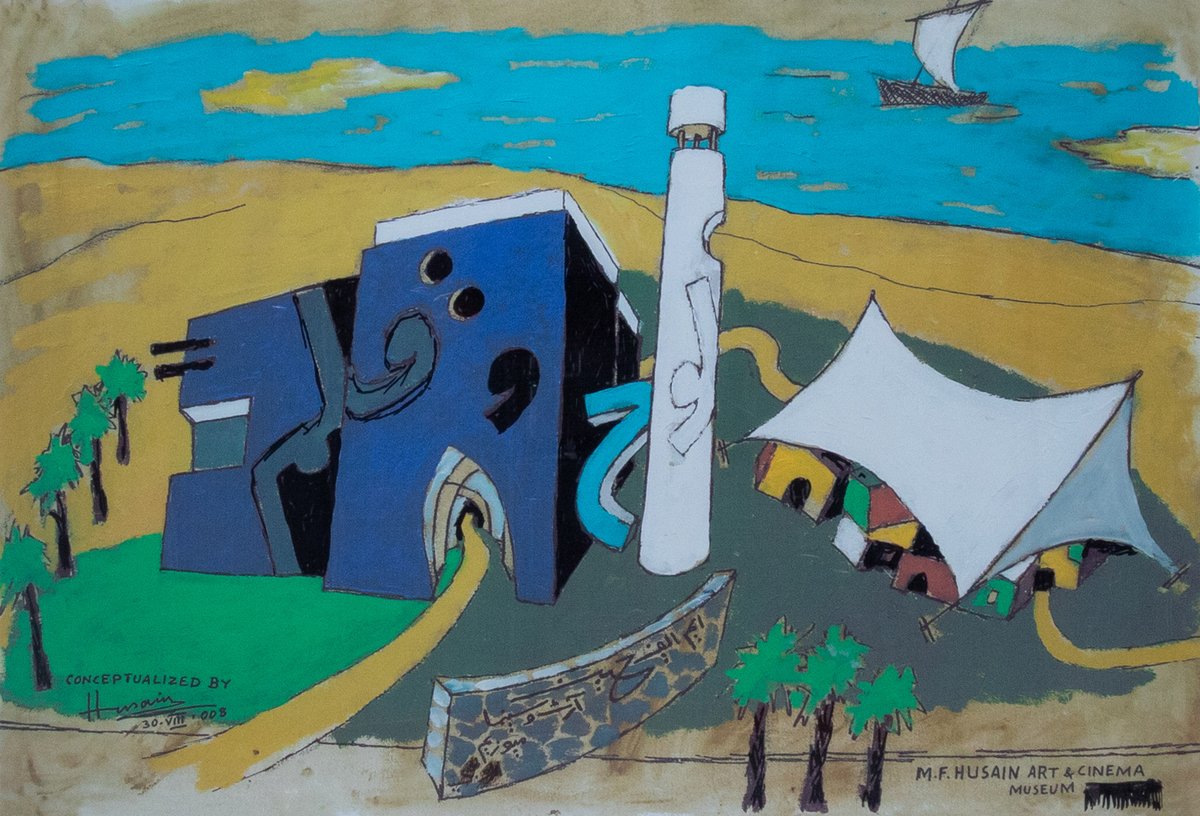

Martand Khosla: The literal reading is that there is a blue house and a white tower. But in our discussions during the early stages, we were thinking, what is the significance of blue? Is there a reference here to the tiles from Central Asia that came to South Asia? There is a sailboat in the backdrop. Does this indicate a space or the centuries-old trade relationship between South and West Asia?

It’s also a cityscape, which could be a reference to Yemen, but it looks very much like many cities of India, where you have incremental urbanism and need-based buildings. It has a tent. Are we looking at all of these cultural markers within the drawing? How do you then derive an architectural language from that sketch? And what are the clues that it leaves that we can think about in terms of institutional architecture?

How did you approach the palette and materiality in this translation?

The surface is blue tiles, which the sketch does not necessarily indicate. Some of the cues for us were that Husain designed a home in New Delhi with broken stone as a façade. And then, of course, the Husain Doshi ni-Gufa in Ahmedabad [an underground gallery of Husain’s work, designed by the architect B.V. Doshi and now known as Amdavad ni Gufa]. That has broken tiles, which are a part of Indian architectural language: they’re often used on the roofs of buildings to reflect the heat. Tiles hold in them a cultural strength and a story that talks about the broader identity of Asia and the region, which informed Husain’s artworks so much.

What about the choice of site?

Before we were appointed and long before the construction of the museum started, a cylindrical glass building was built called the Seeroo fi al Ardh. Within it is Husain’s last major work. It’s sculptural but also kinetic, and it’s a bit like a performance piece in a circular, circus-like manner. The idea is that the viewers can begin their experience of the museum from that building, or they can end it by seeing the grand performance that happens there.

The finished building of Lawh Wa Qalam in Doha retains the key elements seen in M.F. Husain's drawing Image courtesy Qatar Foundation

How does the design relate to your own personal approach as an artist and architect, particularly with regards to the body moving through space?

When you look at it, the museum has an informal massing—almost like a street in one of the cities of the Global South, which is a place where I believe Husain would have grown up. It’s not made by architects and doesn’t hold within it grand cultural institutions. It’s often overlooked, but it is very much the dominant architectural and urban landscape. This is also what we hope will be the journey through the museum for the visitor: to be ambling through the streets of an imagined city, not necessarily following a prescribed trajectory or a chronology. It really does feel like you’re navigating the streets of a city of India, or Souq Waqif in Doha.