Last month we revealed on our website that a Gauguin sculpture bought by the Art Institute of Chicago ten years ago and described by the museum as a major rediscovery and one of its most important acquisitions of the last 20 years, is a fake. It was made recently by the Greenhalgh family in Bolton, Greater Manchester.

Following the sentencing of the Bolton forgers, Scotland Yard told The Art Newspaper on 26 November that a forged Gauguin ceramic of The Faun had also been sold by the Greenhalgh family. The police said that the Gauguin’s “current whereabouts are unknown”. We then tracked it down to Chicago.

The Faun had been consigned to Sotheby’s by Mrs Roscoe, the maiden name of Mrs Olive Greenhalgh. It was offered for sale in London on 30 November 1994 (lot 114), with a note in the catalogue entry stating that it would be “included in the Gauguin catalogue raisonné being prepared by the Wildenstein Institute”, the recognised arbiter of authenticity. Estimated at £20,000-£30,000, it was bought for £20,700. Gauguin’s sculptures sell for relatively modest sums compared to his paintings, although this seems a low figure. At the time there were apparently no concerns about authenticity.

The buyer was London dealers Libby Howie and John Pillar, who were impressed with the sculpture and astonished to be able to buy it at the lower estimate. They kept it for several years, but on an occasion when Chicago’s distinguished chief curator Douglas Druick came for lunch, he spotted the work and was very keen to acquire it. Although the Art Institute has a very fine group of Gauguin paintings and works on paper, it had no sculptures. The 1997 price was £180,000, funded partly by the Art Institute’s Major Acquisitions Centennial Endowment.

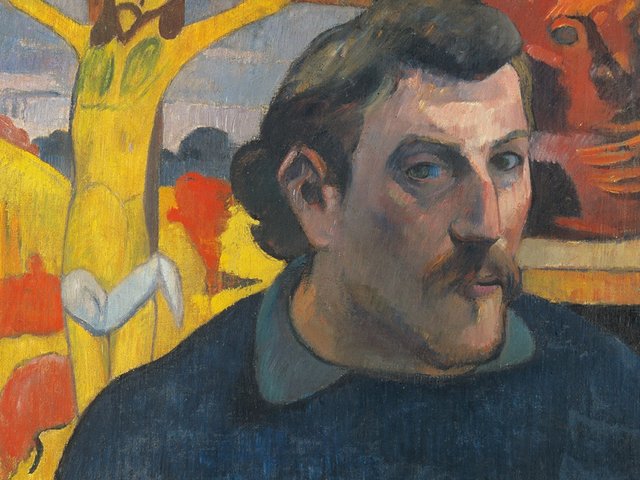

The Gauguin purchase was greeted with acclaim. Writing in Apollo in September 2001, Art Institute sculpture curator Ian Wardropper recorded it as one of the most important acquisitions of the past 20 years. He described the faun’s features, as “bound up with the artist’s self-image as a ‘savage’.”

That same month The Faun was displayed in Chicago’s definitive “Van Gogh and Gauguin” exhibition, which went on to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. Mr Druick dated the work to winter 1886, which made it Gauguin’s “first ceramic”. In his description, he noted the “potentially phallic tail, but parted legs reveal the absence of the often flaunted sign of a faun’s virility, resulting in an aura of impotence. Gauguin evidently linked this iconography to his failing relationship with [his wife] Mette.”

In 2002, The Faun was included in a publication on the Art Institute of Chicago’s “Notable Acquisitions”. Sculpture curator Bruce Boucher wrote that it reflected the disintegration of both Gauguin’s marriage and the certainty of his former life.

The Faun was accepted in 2005 by the leading specialist in Gauguin ceramics, Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark, from Copenhagen, who described it as “among Gauguin’s most satirical” works. She proposed that “the features of the faun (a symbol of unrestrained sexuality)” were not those of Gauguin, but his Danish brother-in-law, Edvard Brandes, whom the artist disliked.

So why was it that no one seems to have questioned the Gauguin? The sculpture appeared to be based on a tiny drawing of a faun sculpture in a sketchbook which the artist used in Martinique in 1887. A work entitled “Faun” was also listed in a Gauguin exhibition held at the Nunès and Fiquet gallery in Paris in 1917. These references are noted in Christopher Gray’s Gauguin sculpture catalogue (1963) and Merete Bodelsen’s authoritative study of Gauguin’s ceramics (1964).

It seems that the Greenhalghs set out to recreate this missing sculpture. What is astonishing is that they were able to design and fire such a successful stoneware forgery, which had no obvious features to reveal it as a modern fake. Ms Howie, an experienced dealer, was originally captivated by the work: “We lived with it, and I cannot tell you what pleasure it gave us. It was a wonderful object.”

The attribution was strengthened by what appeared to be a convincing provenance. According to the Sotheby’s 1997 catalogue entry, The Faun had belonged to the artist Roderick O’Conor, a friend of Gauguin in the 1890s. However, although O’Conor was given some works by Gauguin, this one is said to have been bought from Nunès and Fiquet in 1917, and then to have passed down his family. It is unclear whether Sotheby’s actually asked the elderly Mrs Roscoe how she was related to O’Conor, who had been born in Ireland and died in France in 1940.

Mrs Roscoe had supplied Sotheby’s with a copy of what appeared to be a Nunès and Fiquet bill, selling The Faun to O’Conor. Superficially, this seemed to present an excellent provenance, although anyone delving deeper might have realised that O’Conor was unlikely to have bought a Gauguin in 1917; indeed in the 1920s he sold the one sculpture that he had been given by the artist.

Mr Druick told us last month that based on recent information from Scotland Yard, the Art Institute now “thinks that The Faun is a creative, well-researched forgery of a lost Gauguin, produced by the Greenhalghs”. The Faun had been permanently displayed in a gallery of Post-Impressionist art, but it was taken off show recently. In a statement on 11 December, the Art Institute said that it is “in discussion with Sotheby’s and the dealer about being recompensed” (p1).

Had the Greenhalghs not been prosecuted over the Amarna Princess, The Faun could well have remained on display as a Gauguin for decades, unrecognised as a modern forgery.