Vincent van Gogh’s most unusual self-portrait is assumed to have been destroyed by fire in the last days of the Second World War, but it could have been looted—and might still survive. The blaze took place underground, almost half a kilometre below the surface.

The Artist on the Road to Tarascon (1888), the greatest treasure of the Magdeburg museum in central Germany, was stored for safety in a salt mine. The fire may well have been used as a cover by looters intent on seizing art treasures during the dying days of the Nazi regime.

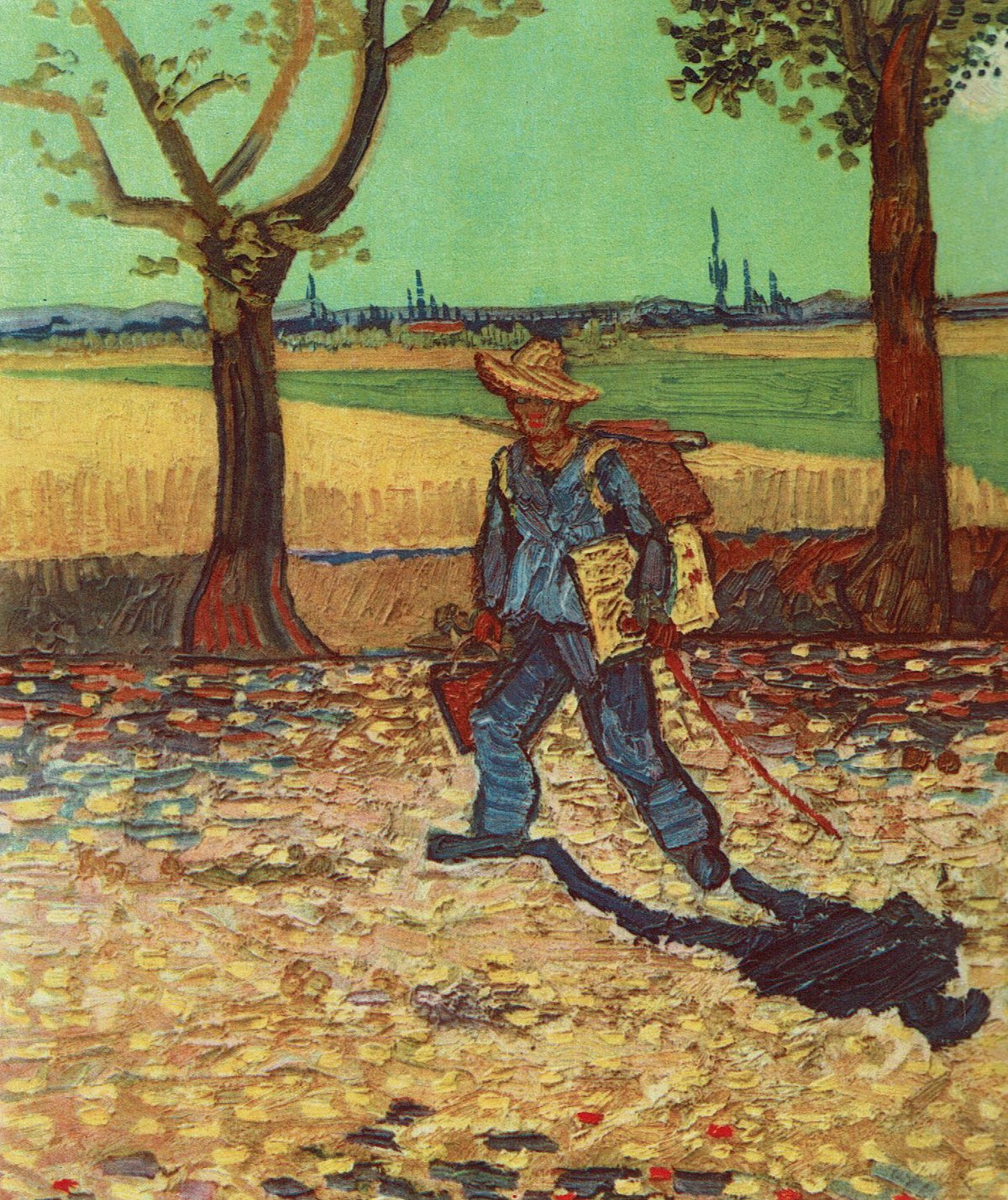

The picture depicts Van Gogh sporting his straw hat, weighed down with his easel and painting equipment. Under a strong sun, he trudges along the road which ran north from the Yellow House in Arles into the Provençal landscape he loved to paint.

On 13 August 1888, Vincent wrote to his brother Theo telling him about his latest picture showing him “laden with boxes, sticks, a canvas, on the sunny Tarascon road”. Van Gogh’s other 36 self-portraits are all heads or heads-and-shoulders and the Magdeburg painting is the only one to clearly depict him in a landscape setting.

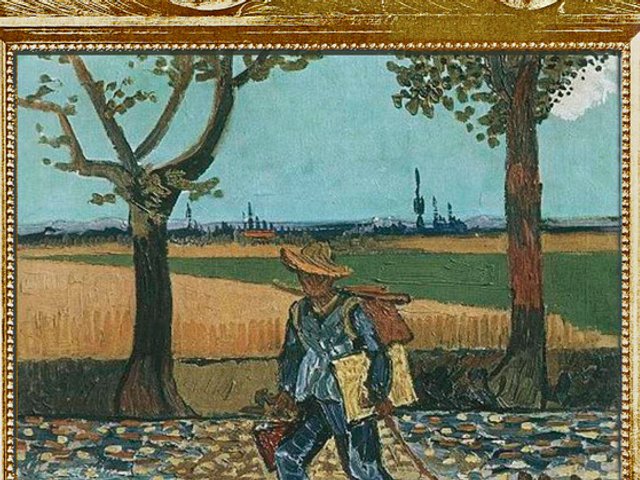

In 1912, The Artist on the Road to Tarascon was bought by the Kaiser Friedrich Museum (now the Kulturhistorisches Museum), making it among the earliest Van Goghs to enter a public collection. Unusually, it was photographed in colour in the 1930s, a reflection of its importance.

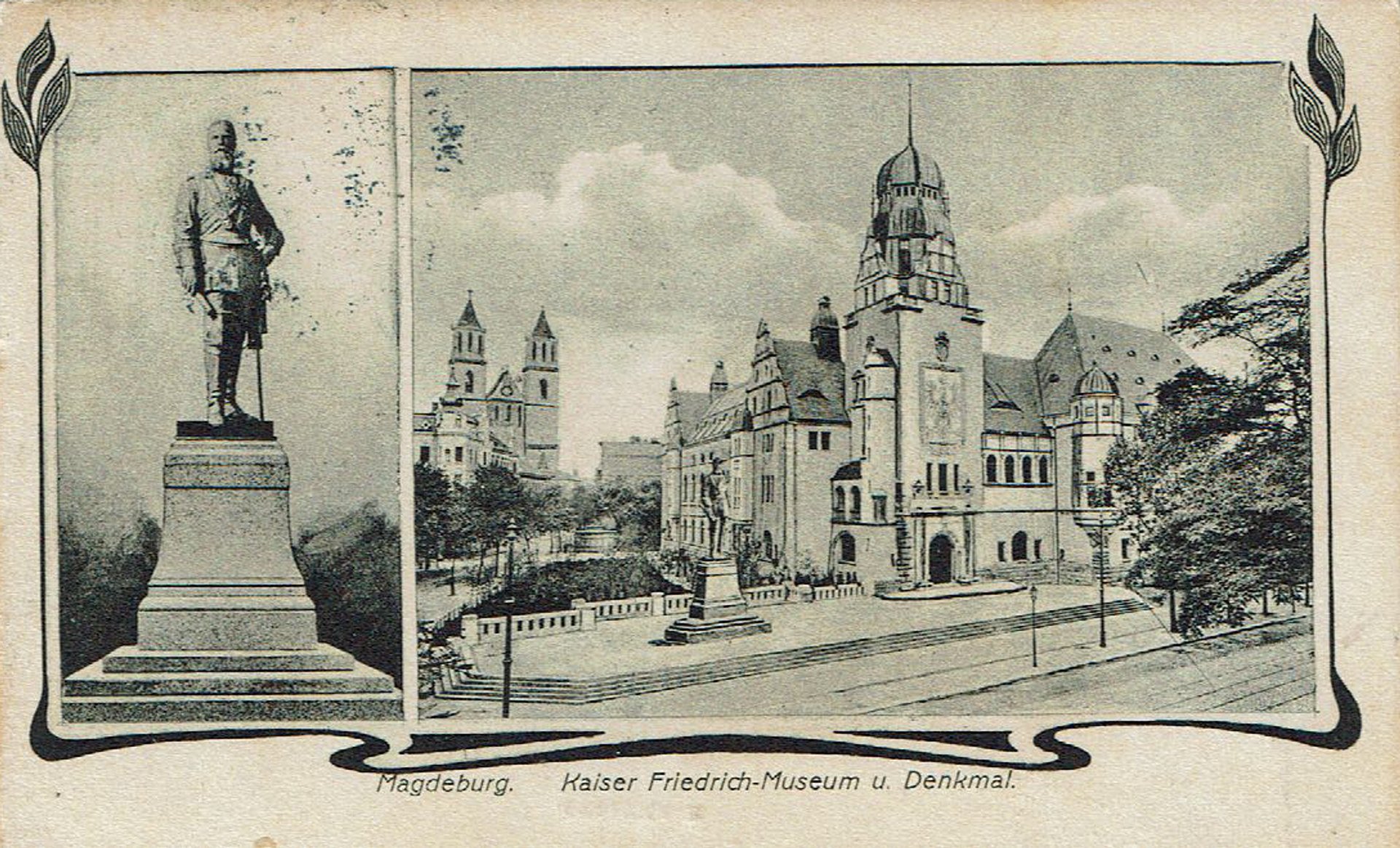

A postcard of the Kaiser Friedrich Museum, Magdeburg (1910)

Although many of the Van Goghs in German museums were sold off by the Nazis as “degenerate”, this one escaped that fate. Fearing British bombing, over 400 of Magdeburg’s paintings were secretly moved to a salt mine on the outskirts of Stassfurt, 30km south of Magdeburg. Evacuation seemed prudent and bombs destroyed part of the museum in January 1945.

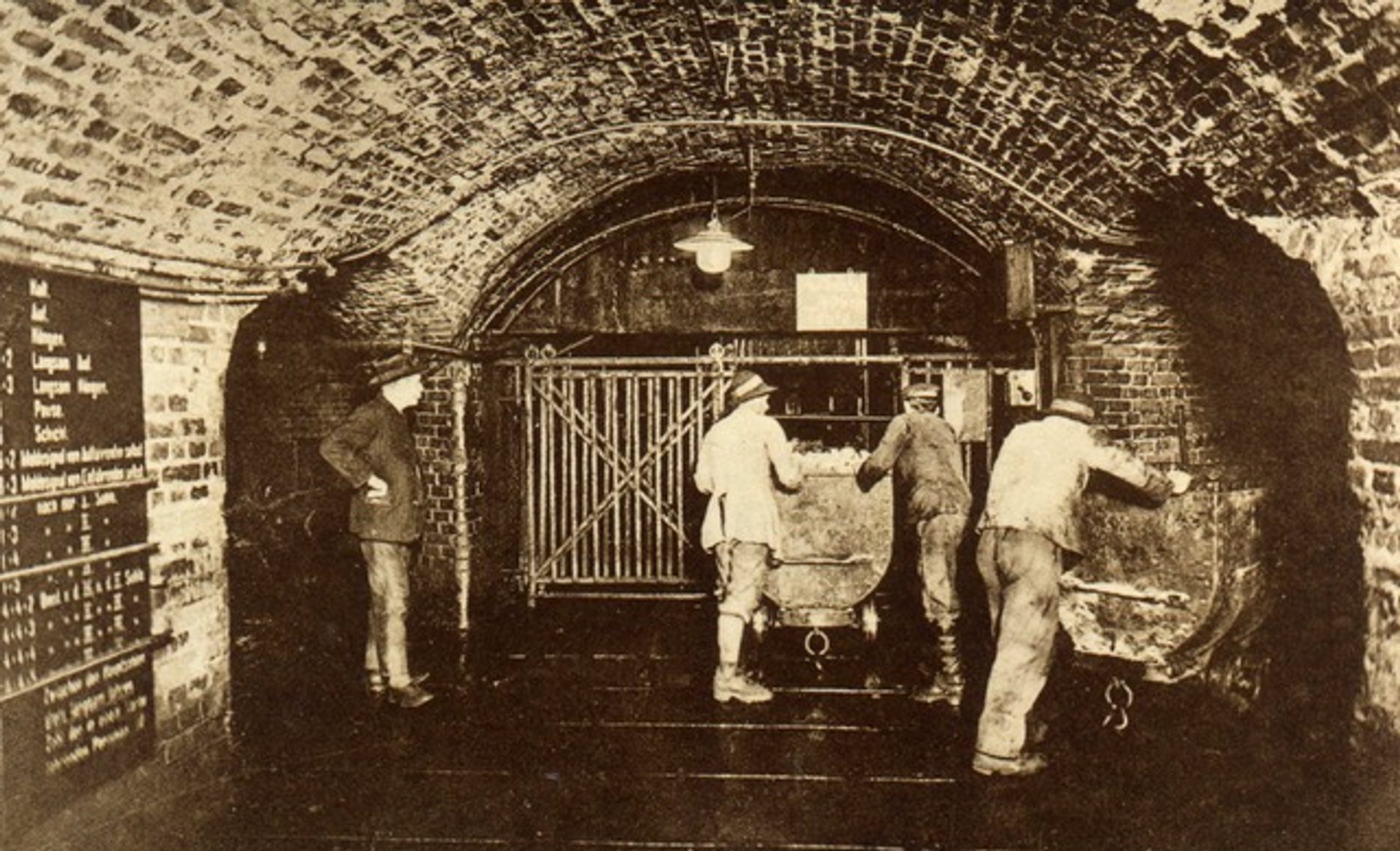

The paintings were taken down to a depth of 460m in the Neu-Stassfurt mine (between shafts six and seven), to be stored in one of voids left after the removal of salt. Immediately above the art collection, at 430m, a secret factory was set up to produce jet engines for Hitler’s Luftwaffe.

A postcard showing the Berlepsch mine at 406m depth, 2km from the art storage mine (1920s-30s) Courtesy Archiv Bergmannsverein, Stassfurt

US troops reached Stassfurt at noon on 12 April. Two fires then broke out in the salt mine where the Magdeburg museum collection was stored, the first just hours after their arrival and the second on 30 April.

Declassified US military documents record: “The fires were stated to have been caused by displaced persons who entered the cave to loot; in the second case, perhaps through the negligence of the US guards. There is no clear evidence whether the fire was set accidentally or deliberately.” The “displaced persons” were Dutch and Polish forced labourers exploited by the Nazis in the underground jet factory.

Tobias von Elsner, a former curator at the Magdeburg museum, believes that the fires are likely to have been arson, perhaps in order to disguise the looting of the artworks. It is possible that the most important paintings were seized, with the packing cases and lesser works then being set alight. The identity of potential looters is quite unclear: they could have been Nazi officials, German civilians, Dutch or Polish forced labourers or US troops.

There is tantalising evidence to suggest that some of Magdeburg’s paintings could have survived. Two objects recorded as having been stored in the mine, a Martin Luther manuscript and a Carl Hasenpflug painting, later turned up after the war and some fire-damaged drawings, sculptures, books and natural history specimens were recovered.

The Neu-Stassfurt salt mines ceased production in 1972 and the shafts were then sealed. On my visit, some years ago, I found a capped circular shaft in remote countryside, surrounded by rusty wire-fencing.

The sealed entrance to shaft seven of the Neu-Stassfurt mine (2009) Photo: © Martin Bailey

Van Elsner has been hunting for the Van Gogh and other Magdeburg paintings for decades and has not yet given up hope: “It is just possible that some survive. As the Van Gogh was the most important in the collection, it would have been a particularly attractive target for looters.”