Vincent van Gogh lived for 53 weeks in the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole from May 1889, after mutilating his ear. There he had little contact with everyday life and none with the art world. But did isolation hinder or help his work?

Life in the walled asylum, in a former monastery on the outskirts of the small town of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, could hardly have been more of a contrast to his time in Paris, where Vincent had lived in 1886-88 with his brother Theo, who ran an art gallery. Paris was then the art capital of the world and home of the avant-garde. Vincent mixed with Toulouse-Lautrec, Degas, Pissarro, Signac and Seurat, as well as Gauguin, who would become his companion in the Yellow House in Arles. It was in Paris that Van Gogh thrust away the dark colours of his earlier Dutch paintings and responded to the sparkling brushwork of the Impressionists.

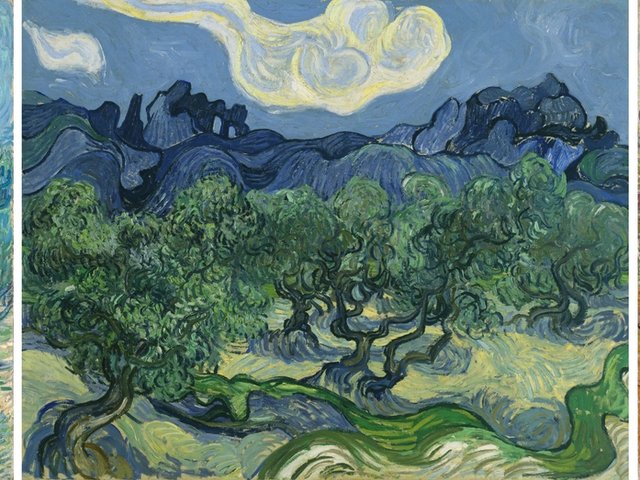

Poster for Maison de Santé de Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (around 1880s) Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

In Saint-Paul-de-Mausole Van Gogh was completely cut off from the art world. For a year he saw no saw virtually no pictures. The only one he mentioned in his letters was a portrait of the abbot’s elderly mother and he may also have contemplated an unremarkable depiction of the Conversion of St Paul in the monastic chapel.

Vincent van Gogh’s Window at the Studio (1889) Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

A recently discovered register of the patients of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole reveals that there were only 18 male residents when Van Gogh arrived. He described these men as his “companions in misfortune”. Most were very seriously disturbed and none had the slightest interest in art. Living in this small community Van Gogh spent most of his waking hours in his two favourite places: the former monk’s cell that he was allocated to use as his studio and the walled garden where he could work outdoors amid nature.

Vincent van Gogh’s Hospital at Saint-Rémy (1889) Courtesy of the Armand Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (Armand Hammer Collection, gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation)

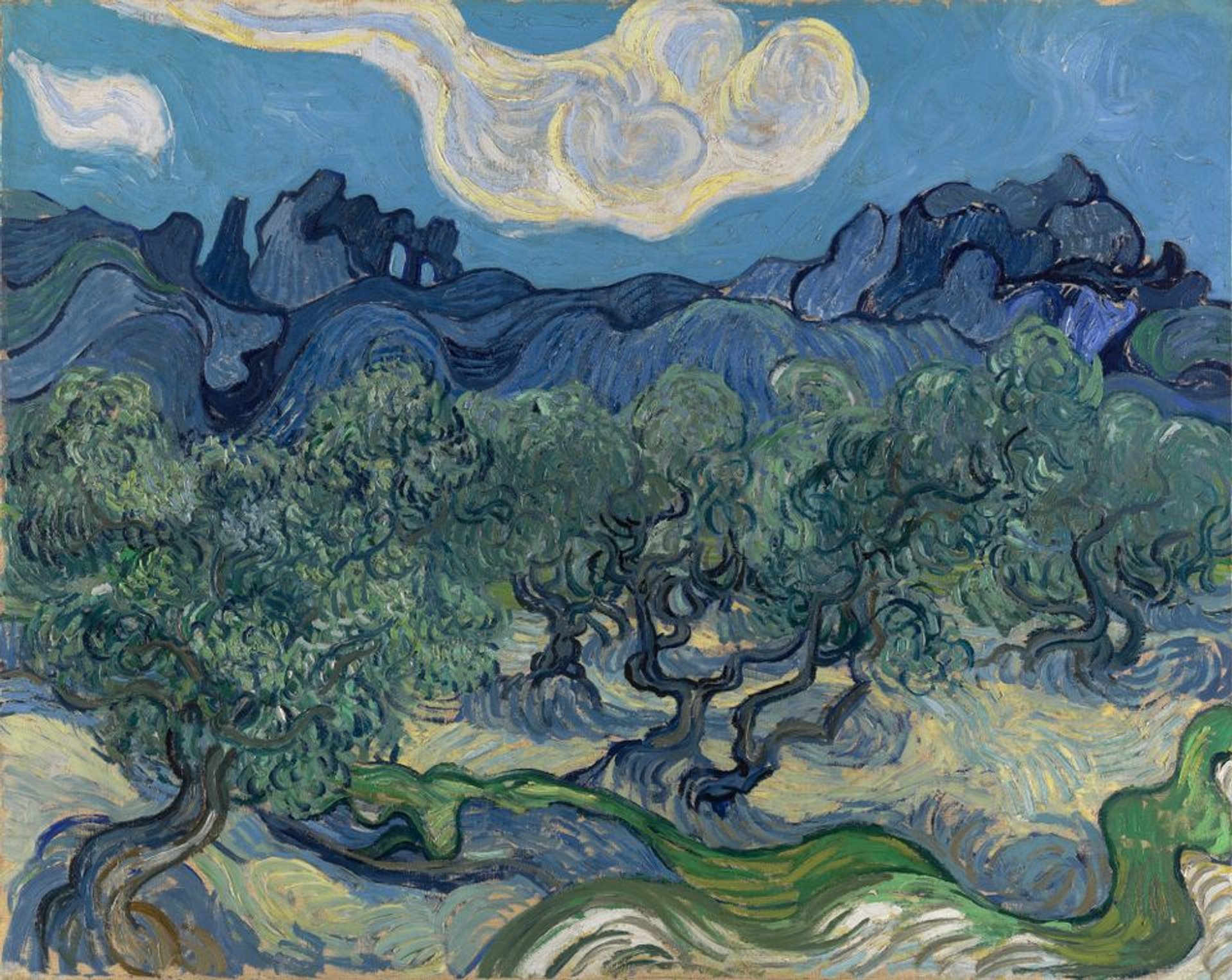

When in relatively good health Van Gogh was also allowed outside the gate for a few hours to paint in the immediate vicinity of the asylum. With the asylum in a beautiful setting amongst olive groves at the foot of Les Alpilles, he drew inspiration from the quintessential landscape of Provence.

Van Gogh’s The Olive Trees with Les Alpilles (1889) Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Not surprisingly, life in the asylum was tough for Vincent, and he was soon desperate to leave. Isolation, he wrote to his sister Wil, was “sometimes as hard to bear as exile”—but it was necessary “if we want to work”.

In terms of his artistic development, Van Gogh’s isolation represented a mixed blessing. It cut him off from his avant-garde circle in Paris, which had been a deep source of inspiration at a key moment in his artistic development—when he was seeking a new means of expressing himself through paint.

But isolation also brought its benefits. With few other distractions, he was able to channel his energy into work, at least while he was in reasonable health. There was no drinking in cafés or fortnightly visits to the brothel. Meals were served to the residents, so he had few domestic worries (he was a notoriously bad cook). Confined most of the time to the asylum and its garden, he studied nature with great intensity.

Vincent van Gogh’s Irises (1889) Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Van Gogh had time on his hands. And he knew exactly what he wanted to do—to paint. He completed 150 pictures in the year and excluding the periods when he was suffering mental crises, this represented one every two days. Without his art, he probably would never have tolerated the indignities of asylum life.

Cut off from the latest art in Paris, Van Gogh followed his own path. Within the asylum’s walls he developed his art in a highly personal and idiosyncratic way, almost uninfluenced his peers or by market considerations. This left him free to take bold artistic decisions, creating the Van Gogh that we now love.

Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889) Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York

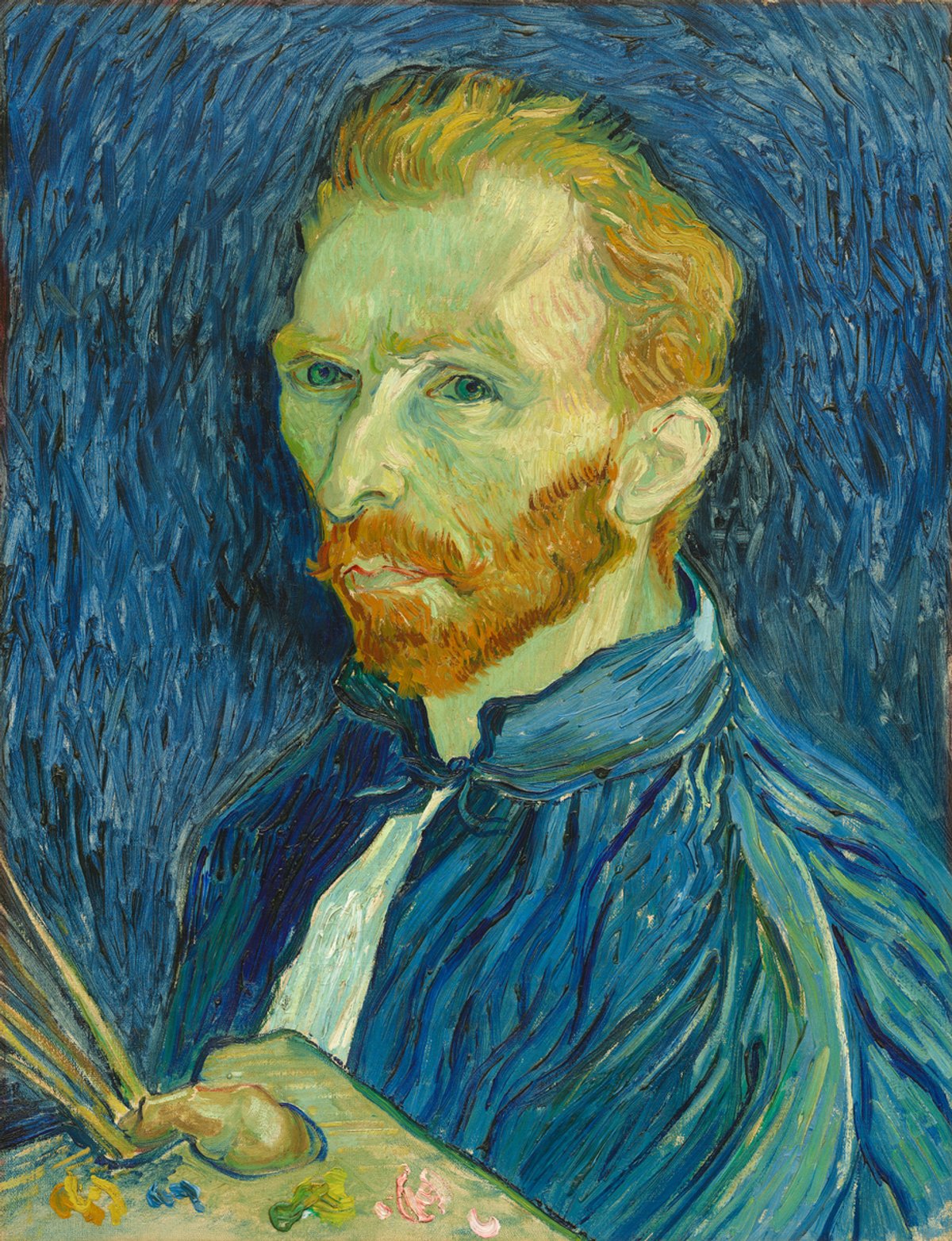

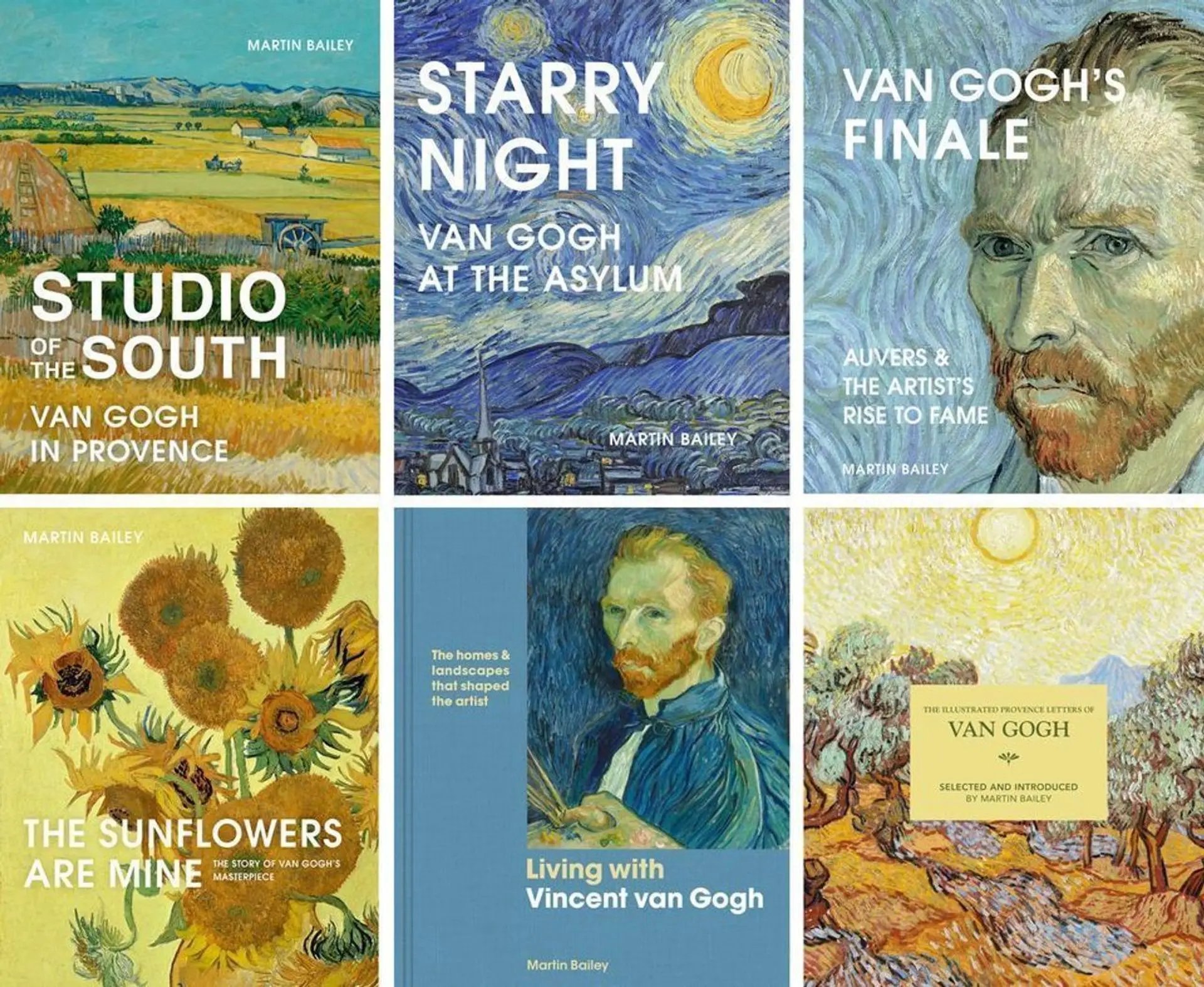

It was at the asylum that Van Gogh painted many of his greatest works, under the most challenging of circumstances. In the garden and just outside the gates he painted soaring cypress trees. There are his olive groves, which will be the subject of an exhibition next year at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and the Dallas Museum of Art. And it was in the asylum that he painted two of his finest self-portraits.

But life was difficult. In May 1890, a few days before his departure from the asylum, Vincent wrote to Theo: “To sacrifice one’s freedom, to stand outside society and to have only one’s work, without distraction… it’s beginning to weigh too heavily upon me here.” He then left for the village of Auvers-sur-Oise, just north of Paris. Ten weeks later his life came to a tragic end.

Other Van Gogh news

• The Dutch police have released CCTV images of the smash-and-grab thief who stole Van Gogh’s The Parsonage Garden at Nuenen in Spring (1884) from the Singer Laren museum on 30 March. The painting was on loan from the Groninger Museum. These images were shown on the TV programme Opsporing Verzocht. They show the thief leaving through the Singer Laren shop holding a sledgehammer and the Van Gogh under the other arm. Images of a motorbike and white van in the street were also released. So far there have been no arrests.

CCTV footage of the crime on the TV programme Opsporing Verzocht