The art world descended en masse last week to the tiny emirate of Sharjah, close to Dubai in the United Arab Emirates, for the opening of the 14th edition of its biennial (until 10 June). This year’s theme, Leaving the Echo Chamber, looks at the role and production of art in an era of fake news, contested histories and fluctuating borders. More than 80 international artists are on show in Sharjah Art Foundation’s myriad of venues, many of which are in and around traditional, historical buildings and some that are off-site.

Hoor Al Qasimi, the director of Sharjah Art Foundation, chose three curators who then collectively developed the theme: Omar Kholeif, Claire Tancons and Zoe Butt. After several editions organised by solo curators, this decision marks a return to the biennial’s earlier format of co-curators. “It is because different people bring different things to the plate and you do not necessarily want to invite one person to do the whole thing—you want certain strengths,” Al Qasimi says. “Omar has a strength in post-Internet art and new media, Claire’s with performance and procession, and Zoe’s with her focus on Southeast Asia. So that was an interesting mix for us.”

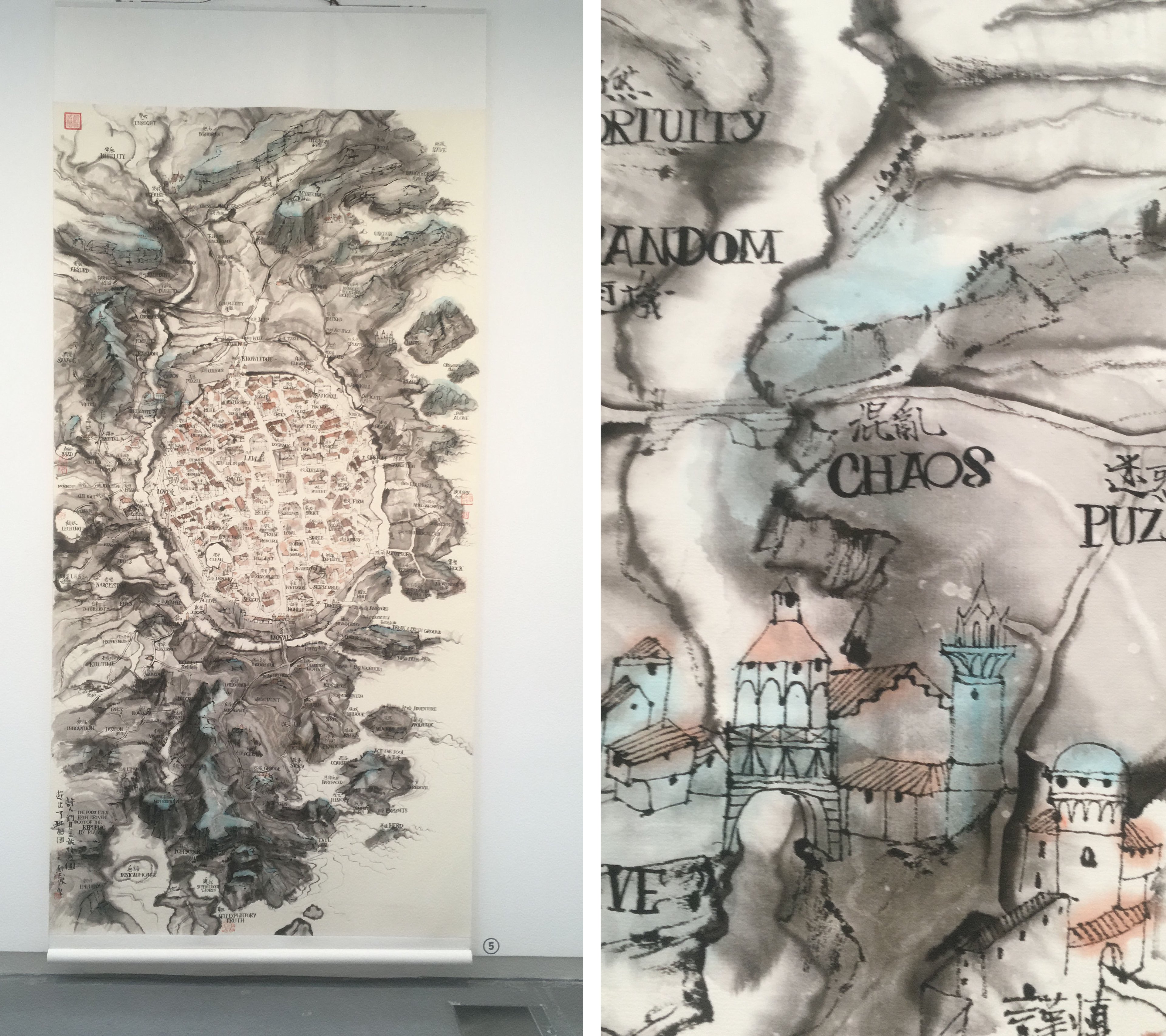

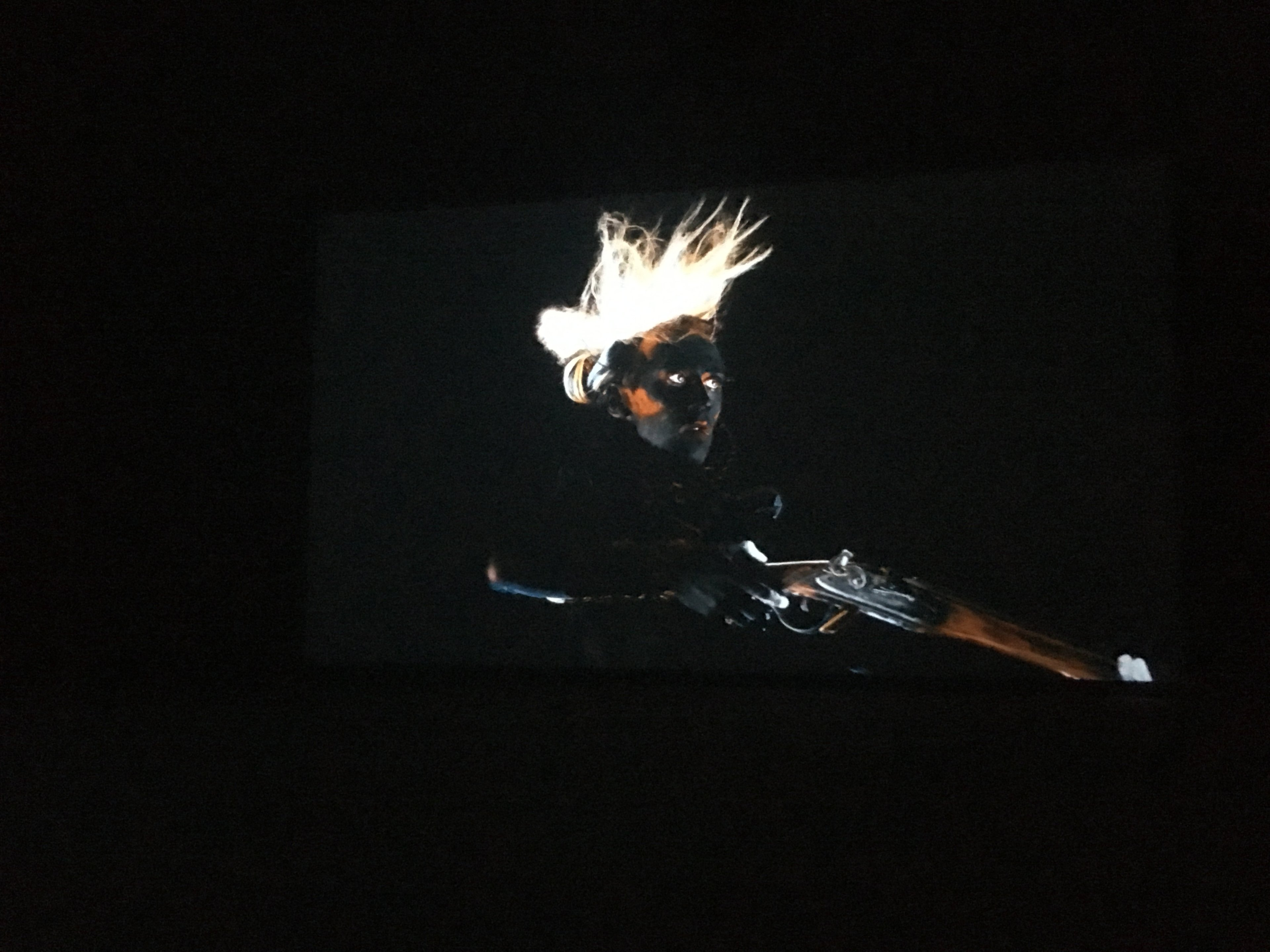

The curators have developed separate exhibitions. Kholeif’s Making New Time looks at how we can slow down our experience of the world in an age of constant, high-speed creation and consumption. Tancons’s performance-focussed programme Look For Me All Around You is centred on diasporic and migratory histories, particularly between the Gulf and the Americas. Butts’s exhibition Journey Beyond the Arrow looks at artists who are re-imagining national and historic narratives, especially with regards to colonialism, social and religious conflicts, and ideological extremism.

Although conceived as distinct shows, the works are in fact intermingled in many of the venues, leading to some confusion and lack of clarity in the curatorial message. The maze of buildings and courtyards can also be difficult to navigate, and the off-site venues in Hamriyah (around a 30-minute drive from the main venues in and around Al Mureijah Square) and in Kalba (around an hour and a half drive) can be hard to get to and easily missed. But Al Qasimi thinks these locations are important. “I am always pushing the curators to use [the off-site locations] and sometimes it is difficult to use many. Eungie Joo [the curator of the 12th biennial] used Kalba and then Christine Tohme [the curator of the 13th biennial] used Hamriyah and then I had the people in Kalba asking why we hadn’t used their site. So it is about having everyone involved and engaged,” she says. It is hard to imagine that many non-local visitors make it out to these locations over the biennial months, particularly as the sites are often activated through performances during the opening days and then left mostly empty.

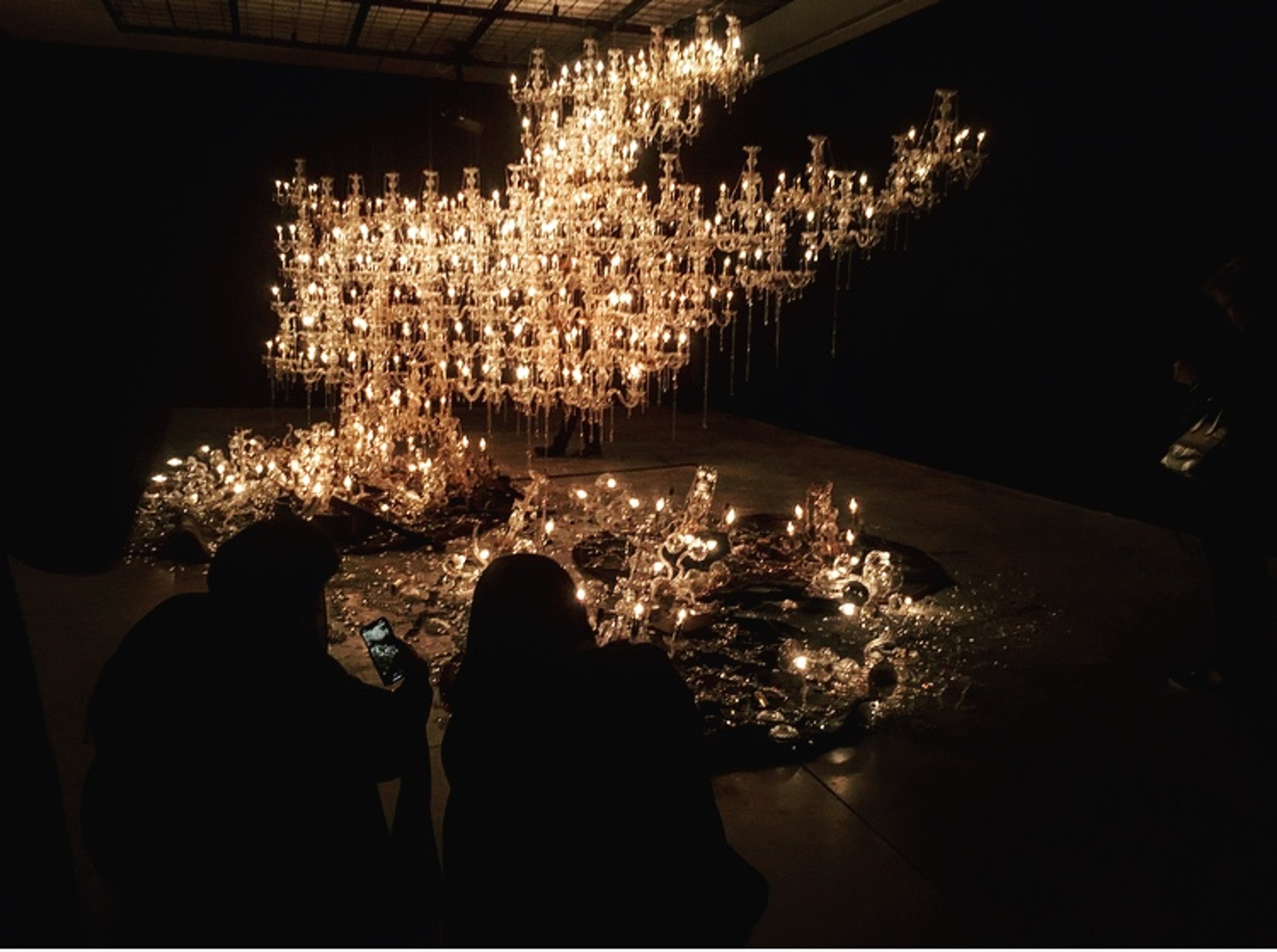

Exceptionally, more than 75% of the works on show in the biennial are new commissions and many are large in scale and scope. This is where the real strength of the biennial lies—in giving both renowned and emerging artists the space, time and funds to create new work. “It’s really rewarding to support these artists and to see them go on after to get more attention, because they are great artists,” Al Qasimi says.

Here is our selection of must-see works in the biennial.