It is no secret that Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) was an early advocate of recycling. One only has to look at versions of his monumental sculptural work The Gates of Hell in the collections of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the Kunsthaus Zurich and Mexico’s Museo Soumaya to find some familiar faces lurking among the 200 figures that make up the work. The Thinker—one of the French sculptor’s most recognisable pieces—occupies a prominent position towards the top of the Gates of Hell, which Rodin began in 1880 and returned to on and off until his death. Simply put, he excelled at fragmentation, assemblage and variation.

The recent examination of the terracotta figures and plaster casts from Rodin’s expressive Mouvements de danse (dance movements) series, which he began at the age of 70, has shown how limbs and torsos from two sculptures known as Alpha and Beta were reused to create figures in positions that pushed the boundaries of what the human body could achieve naturally. The research into the artist’s technical process for this series, for which no documentation survives, is a result of preparations for the exhibition on Rodin and dance, which opened last month at the Courtauld Gallery in London (until 22 January 2017). François Blanchetière, from the Musée Rodin in Paris, co-organised the show with Alexandra Gerstein, the Courtauld’s curator of sculpture and decorative arts.

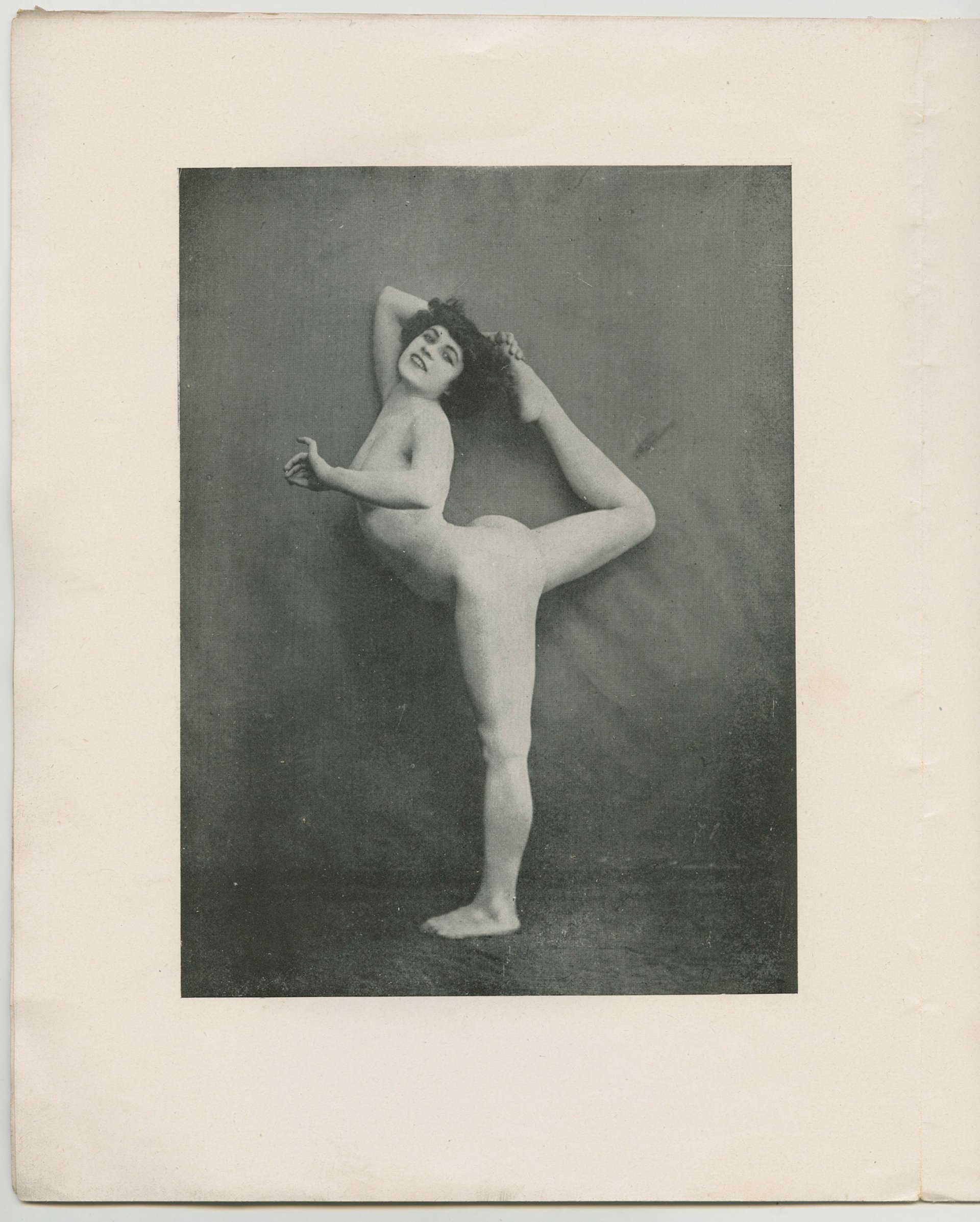

Pressed into moulds An examination of figures from the dance movements series in the collection of the Musée Rodin has revealed that they were formed from existing limbs that had been hand-pressed into moulds; earlier theories had suggested that they were quickly modelled entirely by hand as models such as the dancer and acrobat Alda Moreno posed in front of Rodin.

“They came out of the moulds still wet, so they could be retouched, assembled and then fired,” Blanchetière says.

In many cases, the seams from the mould can still be seen on the figures. Tool marks and fingerprints, showing how Rodin reworked these raw clay figures, are also visible. Gerstein notes that the examination further revealed how Rodin wanted these sculptures positioned; some had areas of flattened clay where they had been set down.

A plaster cast known as Assemblage of Two Figures, called Alpha and Beta (possibly around 1911), is particularly interesting from a technical standpoint. Gerstein explains that as its title suggests, it is formed of two clay figures (Alpha and Beta) that were cast, in pieces, in plaster. The individual plaster body parts were assembled, using incised marks as guides, to make these figures. Rodin then poured plaster slip over the two sculptures to create the finished work, a process that illustrates his expertise at fragmentation and assemblage in achieving the desired composition.

• Rodin and Dance: the Essence of Movement, Courtauld Gallery, London (until 22 January 2017)

• Hell According to Rodin, Musée Rodin, Paris (until 22 January 2017)