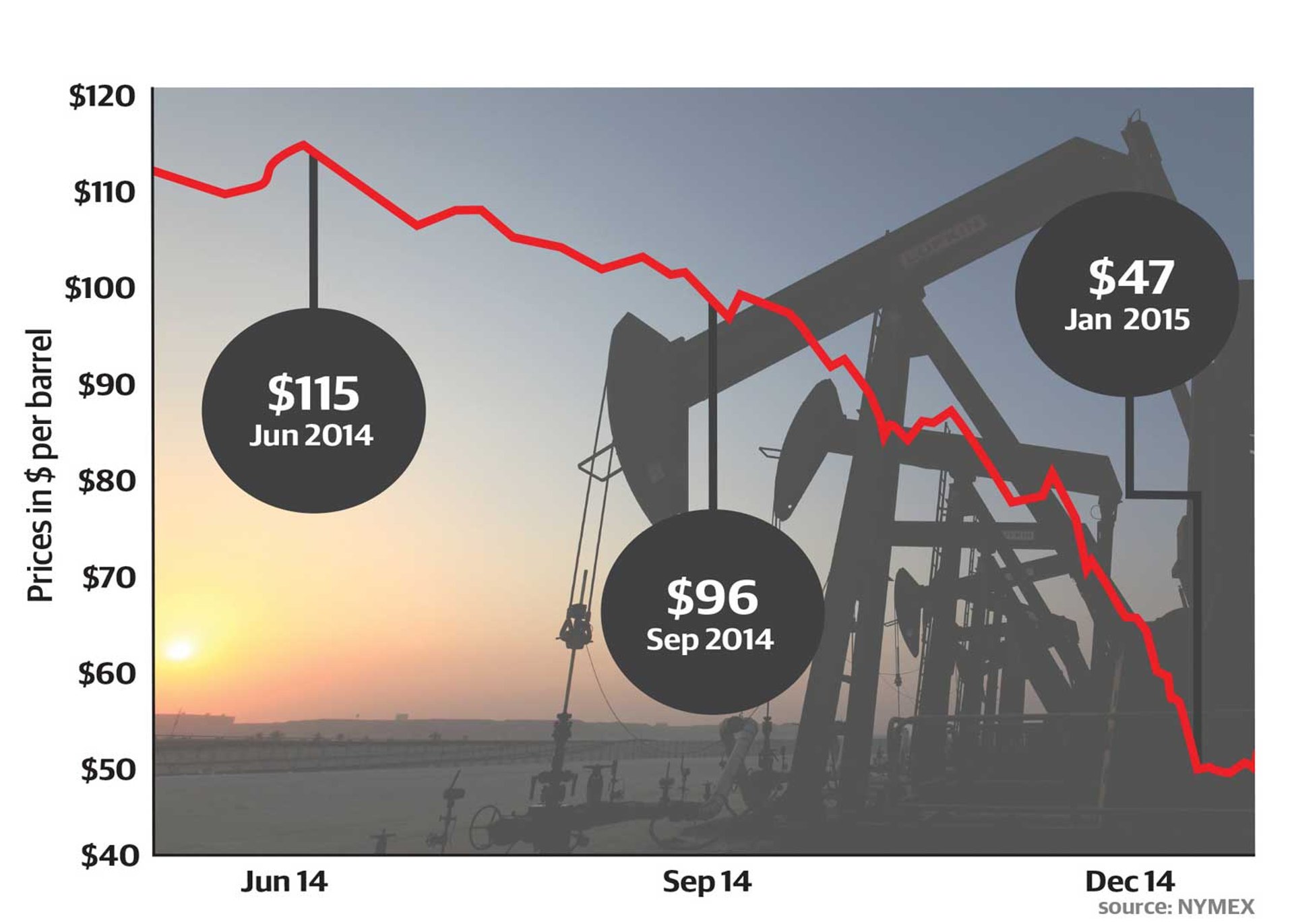

Turn down the music. The economic start to 2015 has been dismal for the wealthy, which spells bad news for the frothy top of the art market. While there is usually an injection of New-Year cheer into the stock markets, January instead suffered global problems that tested such optimism. Crude oil prices dropped below $50 a barrel as we went to press (and are predicted to fall more); growth in China is slowing; the value of the euro against the US dollar has crashed below the 2009 Eurozone crisis level and the impact of clawing back on quantitative easing in the US is unknown, all of which is contributing to a nervous environment.

Art market spin?

The prevailing wisdom, or at least the spin from the art market, is that the business of selling art is immune to the slings and arrows of macroeconomic fortune. Since the protracted wobbles began in 2008 we have repeatedly been told by those in the trade that art represents a “safe haven” in times of financial instability. Many point to overcrowded art fairs buzzing with activity while financial markets waver as a sign that the art world exists in a bubble of its own. Frequently cited examples of art buyers’ defiance of the outside world are Sotheby’s 2008 auction of new work by Damien Hirst in London (which raised £111m on 15-16 September, just as Lehman Brothers collapsed) and Christie’s three-day auction of Yves Saint Laurent’s collection in Paris, which in the midst of the economic doom and gloom of February 2009 made €374m.

Since the protracted wobbles began in 2008 we have repeatedly been told by those in the trade that art represents a “safe haven” in times of financial instability

Like all good spin, this narrative has grains of truth. When traditional assets such as shares and bonds look risky, the wealthy are attracted to alternative places to park their money. And at times of high inflation—when the purchasing power of money falls—certain works of art, in the same way as gold, have been shown to hold (and sometimes increase) their value, at least for a longer period than other assets. More broadly, art buyers, certainly those at the top end, are likely to be immune to some macroeconomic problems. As long as it does not impact too heavily on the money in their pockets, even a global credit crunch can be shrugged off.

It would be wrong, however, to assume that the art market is impervious to all economic developments. A more likely scenario played out in Japan between 1990 and 1992, when the prices of art halved in parallel with a falling Nikkei index. As Noah Horowitz, the director of New York’s Armory Show, writes in The Art of the Deal: Contemporary Art in a Global Financial Market: “The health of the art market during this speculative bubble was firmly anchored to the financial prosperity of its most active constituent.”

And prosperity is still what matters. Although the backdrop has been gloomy in recent years, all has been largely swell for the art market’s most active constituents—the wealthiest global elite, the so-called one-percenters. Quantitative easing, which creates money electronically to buy assets—sometimes described as a policy designed by the rich for the rich—was a direct result of the credit crunch, and restored confidence in the financial system. Asset values shot up accordingly and the well-documented inequality gap grew. Equities, bonds and prime property benefited and a few branded works of art—such as Giacometti’s bronze and wood Chariot (1950), which sold for $101m at Sotheby’s, New York, in November—made nine-figure prices. When 75 works raised $853m in a couple of hours at Christie’s, New York, on 12 November 2014, it allowed auction house specialists to declare that the possibility of a sale of contemporary art making $1bn was real. Such numbers have created what Brett Gorvy, the international head of contemporary art at Christie’s, has called a “virtuous cycle” in which every time a work of art sells publicly for a record, another sought-after work comes to market in the hope of creating another.

Modern Silk Road

What if a new dynamic means the rich get poorer? The oil pipeline has been the Silk Road of modern times (look at the auction houses’ efforts to woo buyers in former Soviet states such as Azerbaijan and Ukraine). Now oil prices are seriously depressed, impacting on stock markets and currencies globally, the holdings of the wealthy are falling in value. Bargains were aplenty at November’s miserable Russian auctions in London (held in the same week that the cover of The Economist read: “Russia’s wounded economy”). A 1930 reclining nude by Zinaida Evgenievna Serebriakova, which sold for £881,600 in 2006, fell to £698,500 in 2014 (having failed to meet a higher reserve in 2012), and a high proportion of works did not sell at all.

In December, the price of crude oil had dropped by 84% in six months—from $115 a barrel to just $47

Often, non-economic policies can have knock-on effects on art sales too. Witness the anti-corruption drive in China, where a crackdown on “gifting”, and lavish spending in general, seems to have created the greatest pinch. Its previously-booming luxury goods market grew by only 5% in 2014, according to Bain & Company, and many believe it could shrink in 2015.

Worldwide slowdown

It isn’t just the Russian and Chinese buyers—who have been responsible for much of the froth in recent years—who are affected. Slower growth is predicted globally for 2015 and there are signs already that the European old guard—a vital backbone of the art market—needs to turn its art into money. Financial woes at Baumax, the Austrian DIY chain, meant that its owner, Karlheinz Essl, had to sell 43 works last October at Christie’s, London, to help secure the future of the rest of his collection. This March, the French businessman Louis Grandchamp des Raux—who was forced to sell his earthenware manufacturing business, Gien, last year—is offering his collection of 17th- and 18th-century paintings, valued at up to €7m (though Des Raux says he is selling to grow his collection of 19th-century works) at Sotheby’s, Paris, in March. In the short term this supplies the market with important work but if consignors need to sell in an illiquid market then prices will fall.

Meanwhile, in the US, which still accounts for the largest proportion of the art trade, particularly in the contemporary and Modern markets, the talk now is all about deflation, which would reverse the confidence-boosting effects of quantitative easing.

This is a market that feeds itself, until it doesn’t

Compounding the negative economic prospects is the way that the rich-getting-richer have ascribed value to art these past five years. This has had very little to do with anything intrinsic. Rather, buyers have been snapping up a limited number of Modern and contemporary artists (ArtTactic, a market research firm, defines 20 such “brands”), plus a few highly-traded younger stars, in the greater-fool belief that another person will always be willing to pay more. This is a market that feeds itself, until it doesn’t.

Such dynamics—regardless of whether there are charts to prove it—rely heavily on confidence, perception and the money in people’s pockets, all of which are threatened in the current economic environment. It looks like it’s time to sober up.

• Melanie Gerlis is the author of Art as an Investment?, published by Lund Humphries