Paris

After the horror of the Charlie Hebdo and kosher-supermarket killings in Paris, the grief, then the nationwide solidarity and the scrutiny of Islamism in its various frightening manifestations, it came as a relief to be immersed for two days in a more hopeful vision for the Arab world.

This was provided by the conference “Renewal of the Arab World”, at the Institut du Monde Arabe (IMA) in Paris on 15 and 16 January. Planned long before the attacks, it suddenly became part of history. As Jack Lang, a famously radical French minister of culture throughout most of the 1980s and now head of the IMA, said at the opening: “We are celebrating the creativity and vitality of the Arab world, so alien to the fanaticism we have just experienced.” The French president, François Hollande, cleared his schedule to inaugurate the conference and made an impressive and well- received speech in which he emphasised the diversity of the French people, “many with links to the Arab world, who come from North Africa and the Middle East, whether Jewish, Muslim or Christian, believers and non-believers, but all contributing, generation after generation, to the history of France”.

“The time for a renaissance has come”, Hollande said, “not just for the Arab countries but for Europe and the rest of the world”; it would be the Arab women and the young who would be the agents of renewal, he predicted, reminding listeners that 45% of the 400 million Arabs are under 20 years of age (compared with a median age of 40 in France).

There were indeed nearly as many female speakers as male from across Middle East and North Africa, 33 of the 67, contributing not only to the subjects where traditionally they preponderate—culture and the role of women—but also entrepreneurship, energy, urban planning and education.

Culture came last in the programme, whether on the principle that people should leave with the most enjoyable ideas freshest in their minds, or because the organisers thought that it rides on the more structural issues. And indeed, what was probably the weightiest cultural insight emerged in an earlier session, on teaching: most of the schooling systems in the Arab world depend on learning authorised texts by heart and instil a fear of failure in the students. At best, this has a stultifying effect on society, but at worst, it prepares minds for brainwashing by fundamentalists.

In fact, the cultural talk was largely about the role that art can play in providing alternative ways of thinking, and about providing activities and spaces where people can come together, discuss and experiment. The Egyptian Ammar Abo Bakr gathers a large team of young assistants around him to carry out his huge graffiti paintings in the streets where the police have killed demonstrators. Hind Meddeb, the Franco-Tunisian documentary-maker, says that the West thinks there is nothing but the military or the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, but she has spent time with, and filmed, the thousands of young people who dance in the streets at night to an utterly disaffected, irreligious rap called “electro chaabi”. Aadel Essaadani, who turned former abattoirs in Casablanca into a space where anyone wanting to be creative could come and do their own thing, now presides over Arterial Network, which links cultural organisations across the African continent. Lina Lazaar Jameel has exhibited photography by Filipinos in Jeddah, and invited them to the opening to rub shoulders with the Saudis, who usually treat them as an invisible underclass. Sheikha Mai bint Mohammed Al Khalifa in Bahrain and Hoda Kanoo in Abu Dhabi both run foundations to enable young people to express themselves and encounter many forms of art.

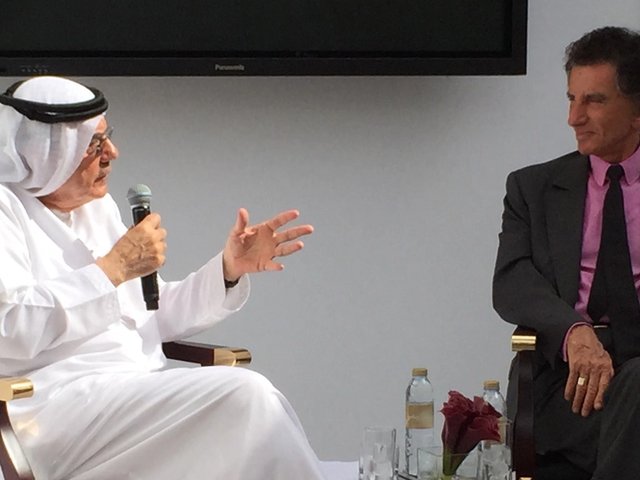

Zaki Nusseibeh, the cultural adviser to the president of the United Arab Emirates and éminence grise of the cultural scene in his country, ended his speech with a deeply felt denunciation of “the ignorance and obscurantism that are perverting religion and culture with a single revengeful, violent and nihilistic objective. We must reclaim our values: that is the most urgent responsibility of our generation.”

Lang announced at the end that a second edition of the conference will take place in 2016.