Over three generations, stained glass has been the business of one branch of my husband’s family. Its inception in 1900 is pinpointed in Peter Cormack’s major study of Arts and Crafts stained glass. Henry Payne, founder of the family studio, was taught by Christopher Whall, subject of an exhibition at the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow in 1979 and of many of his published writings to date. Effectively, the book on Whall that he could write is embedded here. A long career at the gallery steeped Cormack in Pre-Raphaelite stained glass, but it also equipped him to uncover the originality of those who succeeded Morris and Burne-Jones (or their indebtedness, as in the case of the Birmingham followers, of whom Henry Payne was one) and to map their individual identity.

Thirty years in the making, a succession of articles predicted its direction. Here a corpus of little-known works – many of them still in situ, a logistical problem all its own – is added to the coverage of this art movement in Britain and America. Even many of the names, and the ever-shadowy women, are unfamiliar. Cormack makes a bold claim for parity of men and women in stained glass that was not otherwise equalled in the applied arts. Payne himself plays an important role, receiving the attention he deserves in this, his main artistic activity besides murals and late Romantic subject painting.

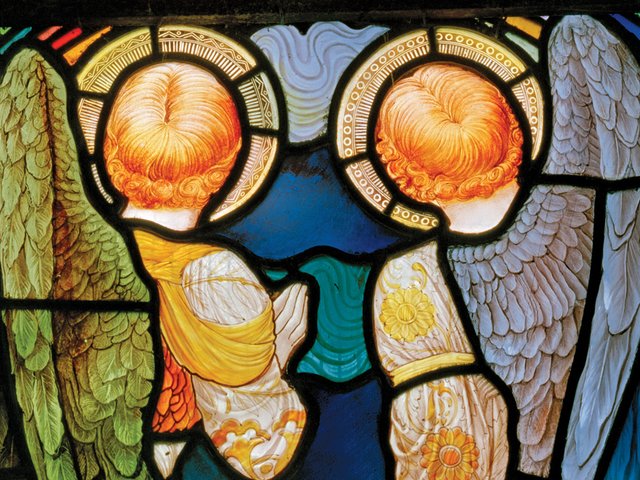

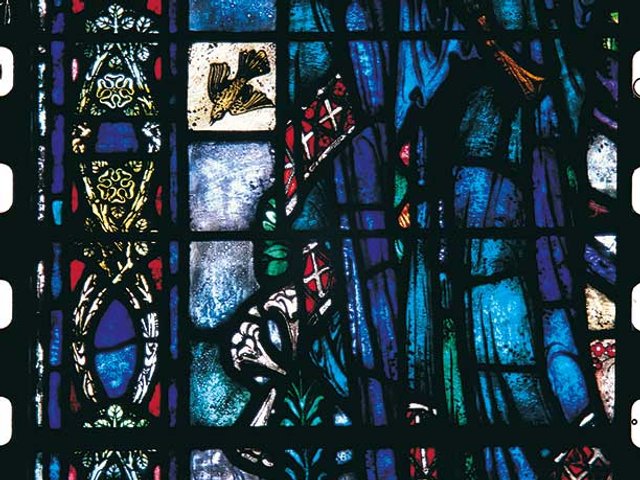

Stained glass is, by its nature and purpose, almost impossible to cover meaningfully in exhibitions. It occupies a position akin to mural painting, of great significance in its own time and later imposing such difficulties of access that it is left out of the narrative. In both cases, contemporary periodicals show important schemes involving the foremost practitioners of the time in foggy black and white reproduction, no inducement to enquire further. Only in extremis does Cormack resort to illustrations from The Studio and The Builder, or textbooks by, for example, Whall and Henry Holiday.

Henry Payne’s son Edward (himself a stained glass artist) remarked that with the largest windows it was impossible to judge their effect in the studio, where they were assembled piecemeal and a final verdict had to wait until they were installed, when it was too late to correct them.

The first chapter usefully lays out the characteristics of the stained glass revival in the earlier 19th century. The aim of the Arts and Crafts regeneration was to move from formal restrictions imposed by Pugin and the Neo-Goths and then Morris, Rossetti, Burne-Jones and the Pre-Raphaelites. There was a large demand for stained glass, but commercial studios were locked into a repetitive imagery and a catalogue of standard representations. Cormack identifies an Aesthetic strain, not often discussed within the framework of this largely secular movement. This poses an interesting question – is there such a thing as an Aesthetic church?

Once we leave behind the early Arts and Crafts exhibitions and commissions, well-reported in arts periodicals, to encounter the second generation, there are many names rarely mentioned in the extensive literature on the movement. The rewards are considerable, particularly in the case of the emotionally charged memorials that proliferated after 1914–18. Between the wars, Cormack demonstrates how this ancient art form could respond to current trends in sculpture and painting. Scottish, Irish and American artists bring their own cultural heritage into the subject matter. The book is strictly about stained glass, but Cormack’s exploration of the context is illuminating about the Arts and Crafts Movement – widely interpreted – as a whole.

• Charlotte Gere is a writer, exhibition curator and 19th-century decorative arts specialist, with many publications on jewellery, design and historic interiors

Arts and Crafts Stained Glass

Peter Cormack

Yale University Press in association with the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 354pp, £50, $75 (hb)