Richard Diebenkorn (1922-93) is the most high-profile member of the San Francisco Bay Area Figurative Movement of the 1940s-60s and is considered one of America’s most important Modernist painters. He received wide acclaim in his lifetime, and interest in his art has remained constant in recent decades. Any comprehensive study of Modernism in America must include Diebenkorn. The question is, how is he to be categorised: figurative or abstract?

Except for stays in New Mexico and Illinois, Diebenkorn remained a Californian. He studied art in San Francisco and went through a phase of realism influenced by Edward Hopper. Diebenkorn met the older artist David Park in 1946. Park, Diebenkorn and their colleagues in the artistic scene of San Francisco were the Bay Area School, a group of artists who painted with assertive gestural styles and strong colours, often using local motifs even though some of the art was abstract.

In 1947, under the sway of the nascent Abstract Expressionist movement in New York—promoted on the West Coast by Hans Hofmann, Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still—Diebenkorn began to make painterly pictures with no recognisable imagery. Soon he was recognised as one of the leading abstract painters in California. Although stylistically close to Willem de Kooning’s, Diebenkorn’s work has its own flavour and stands independently. Aerial views of desert landscapes began to influence his approach to composition. He flirted with post-painterly abstract in some stained canvases of the early 1950s.

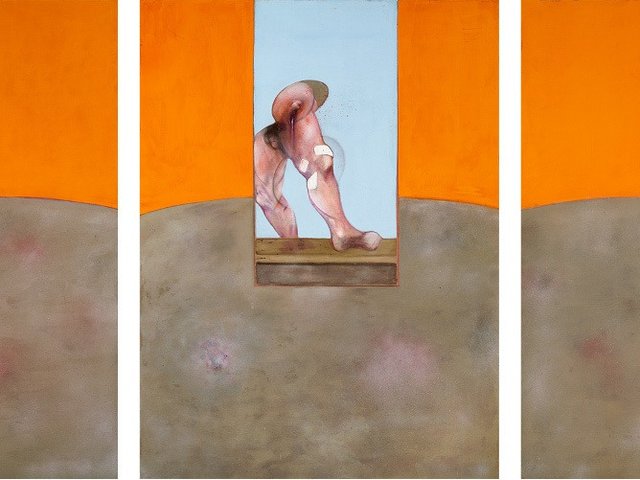

After periods teaching in New Mexico and Illinois, Diebenkorn returned to California in 1953. He was startled by the paintings of Park, who was painting figures at the time. The encounter led him to reconsider what to paint. Over a period lasting roughly from 1954 to 1966, Diebenkorn painted figures, still-lifes, interiors and street views. They were notable for their rich surfaces, strong colour and combination of observed naturalism and attention to abstract composition. Large paintings of figures set against landscape backgrounds were often radically reworked over extended periods. His still-lifes feature fruit and common household objects, usually set against simple backdrops, sometimes reminiscent of Manet’s late still-lifes.

During this period he attended a weekly life-drawing group with Park, Elmer Bischoff and other Bay Area artists. His powerful, strongly outlined nude drawings relate to both his figure paintings and his concerns with the organisation of abstract space. Many hundreds of them are illustrated in volume 3 of Richard Diebenkorn: the Catalogue Raisonné.

In 1966 Diebenkorn moved to the Ocean Park district of Santa Monica, and his art changed again. He stopped making life drawings. Influenced by Matisse and increasingly preoccupied by depicting light, he began the Ocean Park series, which was to occupy his attention until his death. The Ocean Park works are abstract paintings and drawings in vertical format, featuring drawn geometric forms that distantly echo streets and buildings close to the artist’s studio. These works are relatively mildly coloured, and the paint is applied in thin washes. Though the Ocean Park paintings are Diebenkorn’s best-known works, they are also the least accessible. The absence of rich surfaces, intense colours and gestural verve (present in early abstracts and figure paintings) make some of the late paintings seem dry and lifeless. It is possible that Diebenkorn’s figure and still-life paintings may in future be regarded as his most satisfying and accomplished art.

Despite Diebenkorn’s success, two-thirds of his artistic production never left his possession, and this comprehensive publication includes many unexhibited and unpublished works. The first volume of this catalogue raisonné consists of essays covering different aspects of his production, a chronology, bibliography, list of exhibitions and concordance of serial numbers. The following three volumes cover the art in chronological blocks. The roughly 3,750 drawings and paintings on paper are integrated into the body of 550 paintings on canvas. Prints (including monoprints) will be the subject of a future catalogue raisonné.

It is a wise move to combine the media. Although Diebenkorn did not specifically create drawn studies as preparation for paintings, his drawings often include paint, and the paintings rely heavily on drawing. Dates are often speculative as the artist often did not date works, but the broad chronology is fairly clear.

A selection of 119 of the 1,155 works donated by the artist’s widow to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, is illustrated as a representative cross-section. As the cataloguers note, the works in that group were described as for archival research but a number of them are highly finished and comparable to the main body of art catalogued. Some sketches for prints, as well as handmade greetings cards and cartoons are documented and some studio notes are reproduced. A selection of pages from 30 surviving sketchbooks and impromptu drawings in books are also illustrated, with many photographs incorporated into the chronology.

The layout is clear and illustrations generously sized, with expanded analyses and commentary given to key works. The printing and binding of these (heavy) volumes is impeccable. Though not inexpensive, the price for the set is reasonable considering the quality of the publication and the importance of the scholarship.

Alexander Adams is an artist and poet based in Bristol. His latest book, On Dead Mountain, is published by Golconda

Richard Diebenkorn: the Catalogue Raisonné

Jane Livingston, Andrea Liguori, John Elderfield et al

Yale University Press in association with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco