Artists including Sally Mann, Ryan McNamara and Jeremy Deller have spoken in support of Nan Goldin’s push to hold the Sackler family accountable for its role in the US opioid crisis. The family’s fortune stems from the pharmaceutical company that created the highly addictive prescription drug OxyContin.

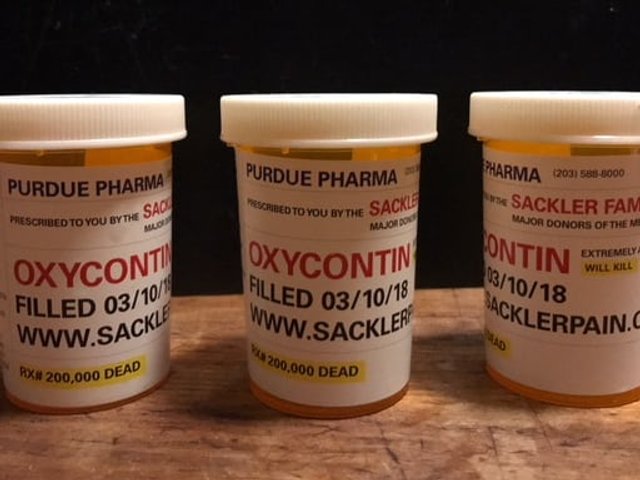

“The Sacklers care about legacy, as can be seen by their name being plastered on institutions internationally, while Purdue Pharma does the dirty work of creating addicts to pay for these family monuments in the background,” says McNamara, who was one of the first to sign an online petition Goldin launched last month calling for the Sacklers and Purdue to fund rehab treatment and addiction education. “As art professionals, we have an opportunity to deny this family that has everything the one thing that they want.”

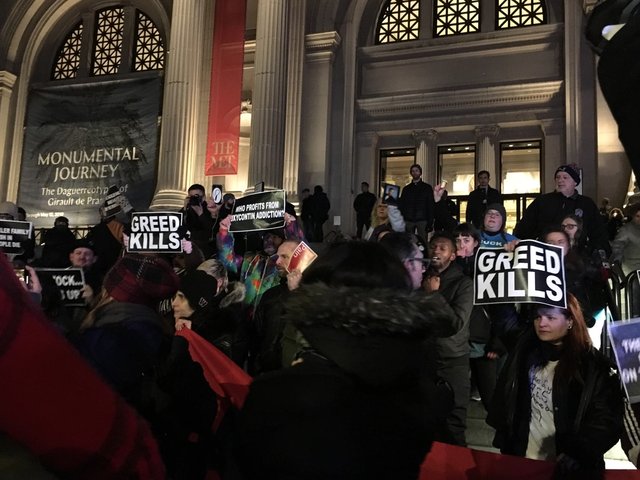

Goldin, a photographer, is known for her uncompromising work, often documenting heroin addiction. Her online petition, which had more than 6,800 signatures as we went to press, aims “to put pressure on museums, art spaces and educational institutions to refuse future donations from the Sacklers” and calls on the family “to respond meaningfully to this crisis”. An accompanying social media campaign uses the hashtags #painsackler and #ShameOnSackler, and Goldin says that her activist group, Pain, plans direct action.

“If the Sacklers’ belief in humanity won’t force them to rectify the epidemic they created, then perhaps shame will,” McNamara says. “I can’t imagine a New York museum opening a Sackler wing at this moment in time, but if they do, I’ll be there with my signs.”

Deller, who says he was not aware of the Sacklers’ connections to Oxycontin—“like most of the art world, I imagine”—before their history was revealed in articles in Esquire and New Yorker magazines, agrees that it is right “to put pressure on the family”. He suggests that the Sacklers meet with representatives from the art world in a non-confrontational way to discuss solutions. “Maybe they don’t care, but at least we should give them the chance, and if they rebuff, then fuck them.”

Elizabeth Sackler, the founder of the Brooklyn Museum’s Center for Feminist Art, says: “The opioid epidemic is a national crisis and Purdue Pharma’s role in it is morally abhorrent to me. I admire Nan Goldin’s commitment to take action and her courage to tell her story. I stand in solidarity with artists and thinkers.” She adds that her father, Arthur Sackler, died in 1987, before OxyContin existed, and his share in the company was sold to his brothers a few months later, so none of his descendants has profited from the drug.

A Purdue Pharma spokesman says: “This company has a strong track record of addressing prescription drug abuse, which includes collaborating with law enforcement, funding state prescription drug monitoring programmes and… supporting drug take-back programmes. We’ve recently announced educational initiatives aimed at teenagers, warning of the dangers of opioids, and continue to fund grants to law enforcement.”

Not all artists find fault with the Sackler family, however. “If we’re going to look at them we have to look at everyone who’s doing something we don’t like,” says Andres Serrano. He adds that the bigger question is why addiction is viewed and treated differently depending on the community it affects, with people of colour more often being sent to prison instead of rehab. “Don’t blame the Sacklers, blame the government for making [Oxycontin] legal,” Serrano says. “The Medicis were no bed of roses either.”