S. Vijay Kumar, a shipping company executive based in Singapore, was instrumental in the return of a 12th-century Buddha stolen in India 57 years ago. It was handed over by UK authorities to the Indian High Commission in London to coincide with India’s Independence Day celebrations in August. Kumar has dabbled in helping India recover its stolen antiques since 2007, co-founding the India Pride Project in 2014 to promote social media coverage of stolen items and releasing his book The Idol Thief in Mumbai, which reads like a whodunit, this summer. He speaks to The Art Newspaper about his investigations, which have led to the recovery of 28 such objects, with many more in the pipeline.

The Art Newspaper: What role did you play in the recent return from the UK of the 12th-century Buddha that was stolen from a Bihar museum in 1961?

S. Vijay Kumar: I was put in contact with Sachindra Biswas, a former head of the National Museum in Delhi who had kept detailed records of two thefts of Buddhas, which India had been unsuccessful in solving since the 1960s. When Lynda Albertson of the Association for Research into Crimes against Art was planning to visit The European Fine Arts Fair (Tefaf) in Maastricht this March, I asked her to keep an eye out for Indian objects on sale.

A London dealer was selling Himalayan Buddhist art including a Buddha that I recognised from one of the images provided by Biswas. Albertson contacted the Netherlands police and I reached out to the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). The dealer was asked to remove the object from sale and to report back to the Metropolitan Police once he was back in London. We also passed on this information to the police. The head of the ASI wrote to the Indian High Commission as well.

The police contacted the International Council of Museums, which arranged for a neutral expert to examine the object and he agreed with our assessment. The owner and dealer surrendered it on condition that their identities were kept secret; a legal case would have been too complicated. It was handed over to the High Commission in August.

I am using Biswas’s records to prove that another Buddha, now in a Los Angeles museum, has also been stolen from India.

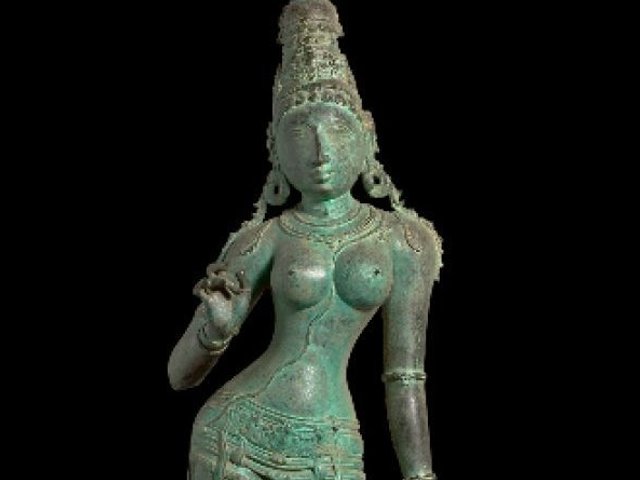

The 12th-century Buddha was returned to India this year after S. Vijay Kumar spotted it for sale by at a London dealer © Metropolitan police/PA

You focus on the plundering by a New York-based Indian art dealer, Subhash Kapoor, who is now in custody in India. Is he the biggest smuggler of Indian antiques abroad?

Actually, Kapoor was an inconsequential dealer and I believe he moved into the space left vacant by larger networks. We have villains like Kapoor almost every decade!

What is their modus operandi?

The networks have been getting more brazen with the high sums involved these days. First were the days of the diplomatic pouch [the secure means of transporting items between a diplomatic mission and its home country], later it moved to getting fakes made, procuring export licences and switching the originals during export. Nowadays with blatant corruption and lack of experts within the system, container-loads go out with just a wrong declaration.

Your list of institutions associated with Kapoor—most of them not illegally—runs to six pages. Can you tell us about the complicity of museums?

The list is from Kapoor’s now-defunct Art of Past website. None of these institutions ever objected to Kapoor openly listing them and projecting his larger-than-life image. US law enforcement had directed all institutions and collectors to review their association with this website. Not a single institution or collector volunteered any information nor made an attempt to declare the provenance of the objects in their collections. This is no flash in the pan; we are in for the long haul.

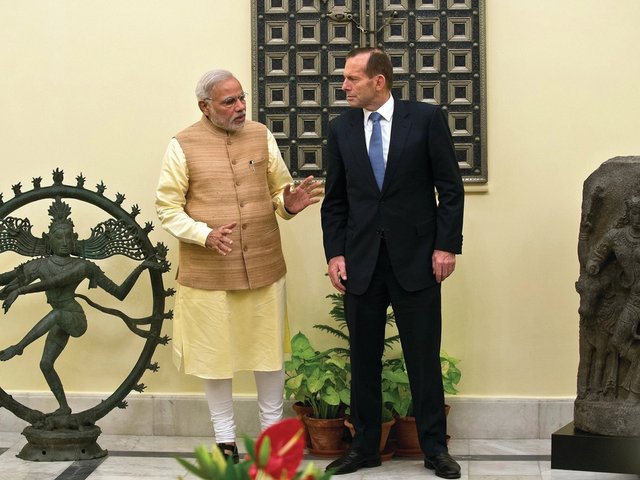

There is a lack of initiative to clean up the wrongs of the past. US museums in the US are still not putting up detailed information even on their purchases; when we get into donations, things get even murkier. The same is true of Australian museums where we have seen lack of due diligence on provenance and also on the cost of the acquisitions. There have also been cases where the curator seems to have rather puzzlingly asked the valuer of a gift to change his valuation and cite a higher value! Sadly, in almost all cases, the worst that seems to happen to such people is a dignified early release or retirement.

While you make a case for retaining ancient idols in temples, not all of them can guard against theft.

This is akin to ivory—when the buying stops, the looting stops. We are also working on building a proper national archive and also a set of red flags for our own custodians. We believe that the art world can do due diligence and ensure that it doesn’t look at source nations as easy targets even when faced with apparently foolproof but fake paperwork. Dealers should not ignore clear give-aways like fresh looting marks, chisel marks on stone and oil stains on bronzes.

You accuse Indian agencies too for their negligence at best and criminality at worst.

Yes, we have not done enough to dismantle the supply chain and expose the criminal nexus. We have online Customs and Enforcement Directorate data for hundreds and thousands of shipments that has not yet been used to secure prosecutions. Art crime is still nascent in India and we hope with the book and my work over the past decade, India will set up a proper art crime unit at the central level and stop this targeted looting of our heritage.

How does a night-time sleuth like you go about their investigations?

It started off as a hobby, like an addictive game, but now it’s grown too big for me. But thanks to social media, our small yet significant successes will surely inspire not only me but also leave a lasting legacy amongst like-minded youth, enthusiasts, experts and organisations who will come out and continue the fight to protect our ancestral treasures and restore India’s Pride. No longer is Indian art fair game for looters—we are watching.