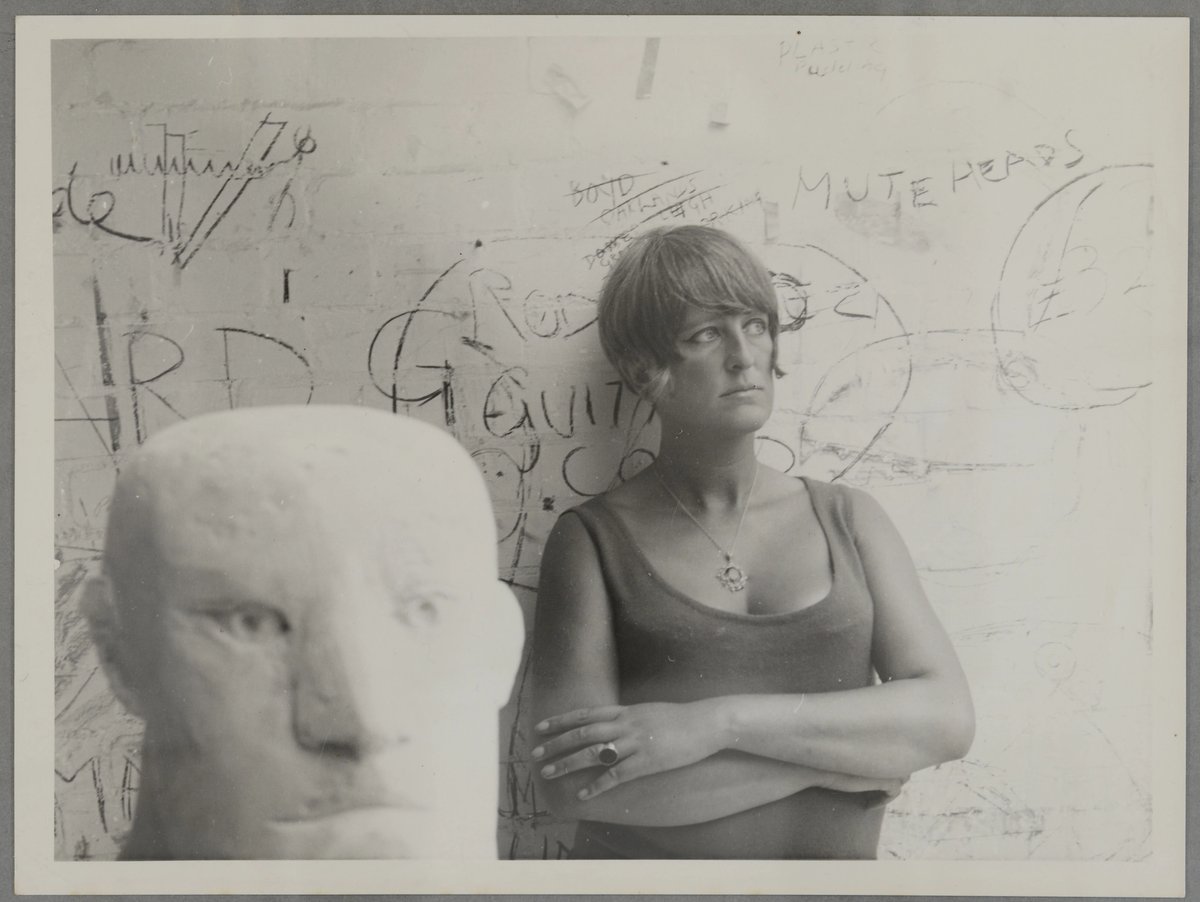

The most extensive exhibition of works by Elisabeth Frink held since the high-profile UK sculptor died in 1993 has launched at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich (until 24 February), encompassing fundamental works such as the Goggle Heads series (1967-69). The show, entitled Elisabeth Frink: Humans and Other Animals, includes more than 130 pieces dating from the 1950s to the 1990s, including Frink's famed expressionist bird sculptures such as Vulture (1952) and works drawing on the theme of the Running Man (1978-80).

Frink studied at the Chelsea School of Art in London, exhibited with the London Group at the New Burlington Galleries in 1952 and participated in the British Council’s exhibition, Young British Sculptors, which toured Germany between 1955 and 1956. In 1985, she was given a solo exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London.However, Frink has been excluded from all major surveys of British sculpture since she was included in a major Tate sculpture show in 1965, writes the exhibition curator Calvin Winner in the catalogue.

“There is a deeper and darker Frink, which she herself acknowledged, but found impossible to articulate in words,” he adds. The show includes many of Frink’s unsettling bird sculptures including Harbinger Bird III (1961) drawn from the Frink Estate and Archive. “The bird-form became a vehicle, or avatar, to explore the Cold War and the climate of fear that shadowed the post-war period. These works evoke an extreme sense of menace, fear and panic,” Winner writes.

A selection of Riace men sculptures (Riace I-IV, 1986-89), shown here as a quartet for the first time in several years, are just as threatening. But with their faces obscured, Frink highlights the vulnerability and tragic aspects of these superhuman warrior figures. The most powerful section in the show comprises several pieces from the Goggle Heads series (1967-69), imposing busts with their eyes concealed behind ominous headgear.

“Frink indicated that the image was impressed upon her by the news media of the time reporting the colonial wars in North Africa; and by General Oufkir, a captain of the French army of Morocco, who allegedly arranged the ‘disappearance’ of the left-wing politician Mehdi Ben Barka,” Winner says. He makes the point that these depictions of “gangland hoodlums” might have been inspired by the goggled motorcyclists in the Jean Cocteau film Orpheus, released in 1950.

Many works on show are on loan from the Frink Estate & Archive in Dorset. Crucially, its curator Annette Ratuszniak points out in the catalogue that the archive “will be spread across museums and galleries throughout England, Scotland and Northern Ireland with opportunities for collaboration, exhibitions, research and greater public access”.

Elisabeth Frink, Goggle Head (1969) Photograph Pete Huggins © Frink Estate and Archive