Is an old mystery about to be solved? A show in Chantilly, just north of Paris, lifts a veil on one of art history’s more enigmatic and oft-derided works of art, a celebrated drawing widely (and wrongly) known as the Nude Mona Lisa because of its formal similarities to Leonardo’s Louvre masterpiece. The exhibition will present detailed evidence that the work, attributed to a follower, may well have been made by Leonardo himself.

And the subject? Definitely not the Mona Lisa, nor Monna Vanna—another fanciful title attached to the work in the 20th century, inspired probably by the friend of Dante’s Beatrice (painted by the English Pre-Raphaelite painter Rossetti). A new interpretation suggests instead that this may be an idealised female portrait, depicting the sitter as Venus, the comely goddess of love. A number of copies and paintings clearly inspired by this prototype will also be on show at the Château de Chantilly (1 June-6 October).

“The painter might have worked on both pieces at the same time”

The drawing had never been subject to detailed analysis until last spring, when it underwent an exhaustive examination by the French Museums Laboratory. Bruno Mottin, who led the research, concluded: “It could well be a work by Leonardo da Vinci. At the very least, all indications point to his workshop and the making of a pretty ambitious work.”

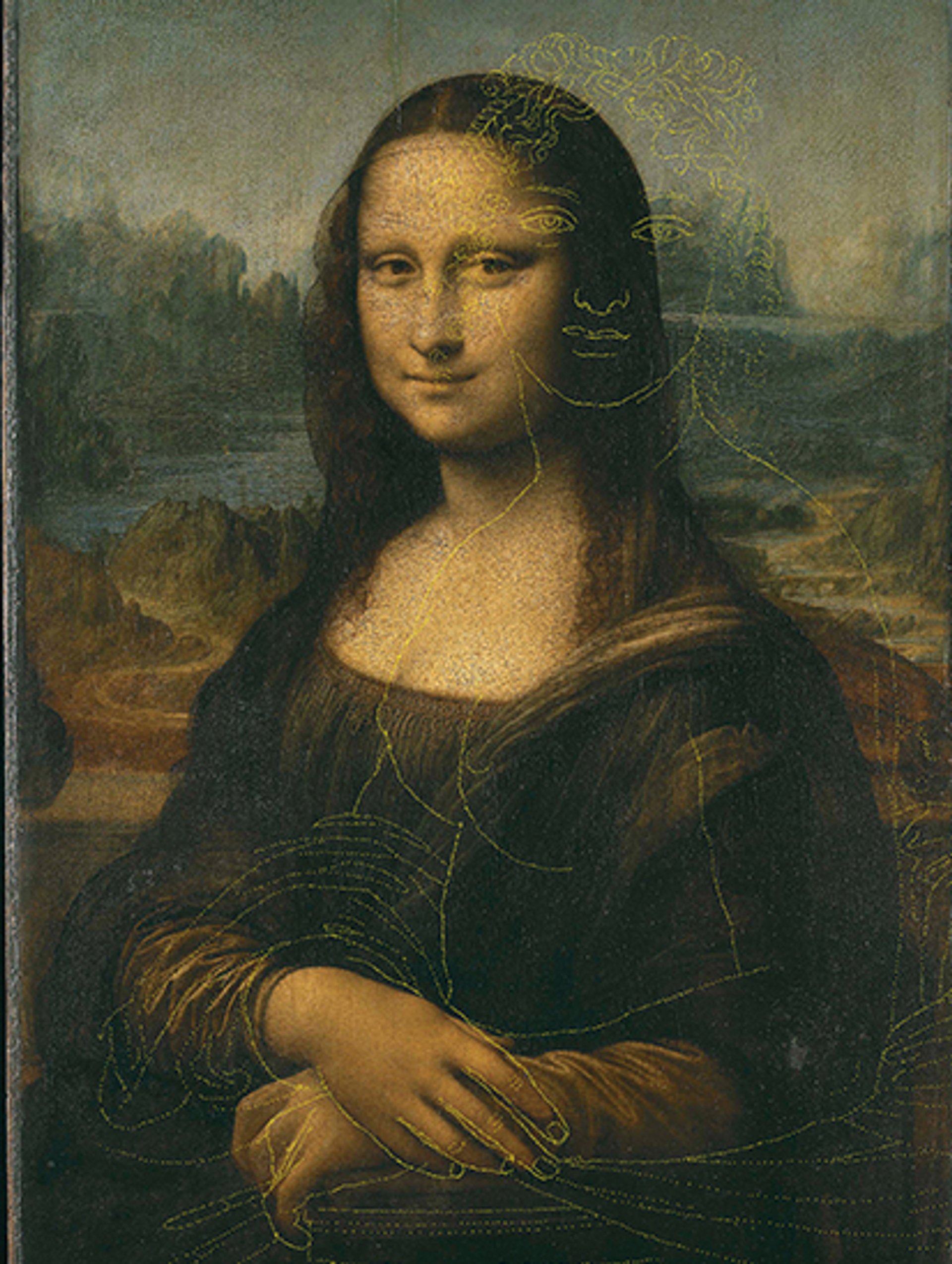

La Gioconda superimposed on Leonardo's Mona Lisa Credit: Bruno Mottin/Elsa Lambert/centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France

It was bought in 1862 by the Duke d’Aumale, son of Louis Philippe I, the last King of France. Sold as a drawing by Leonardo, it was described as “young woman, naked bust”. “Ever since then, everything and its opposite has been said,” says the Chantilly curator Mathieu Deldicque, about a work which “has given rise to the most contradictory reactions and fantasies.” The duke bequeathed his collection to the French Academy on condition that it never leave his château at Chantilly, so there is no way that the Louvre curator Vincent Delieuvin can include it in his forthcoming Leonardo blockbuster. But he has co-curated the show at Chantilly.

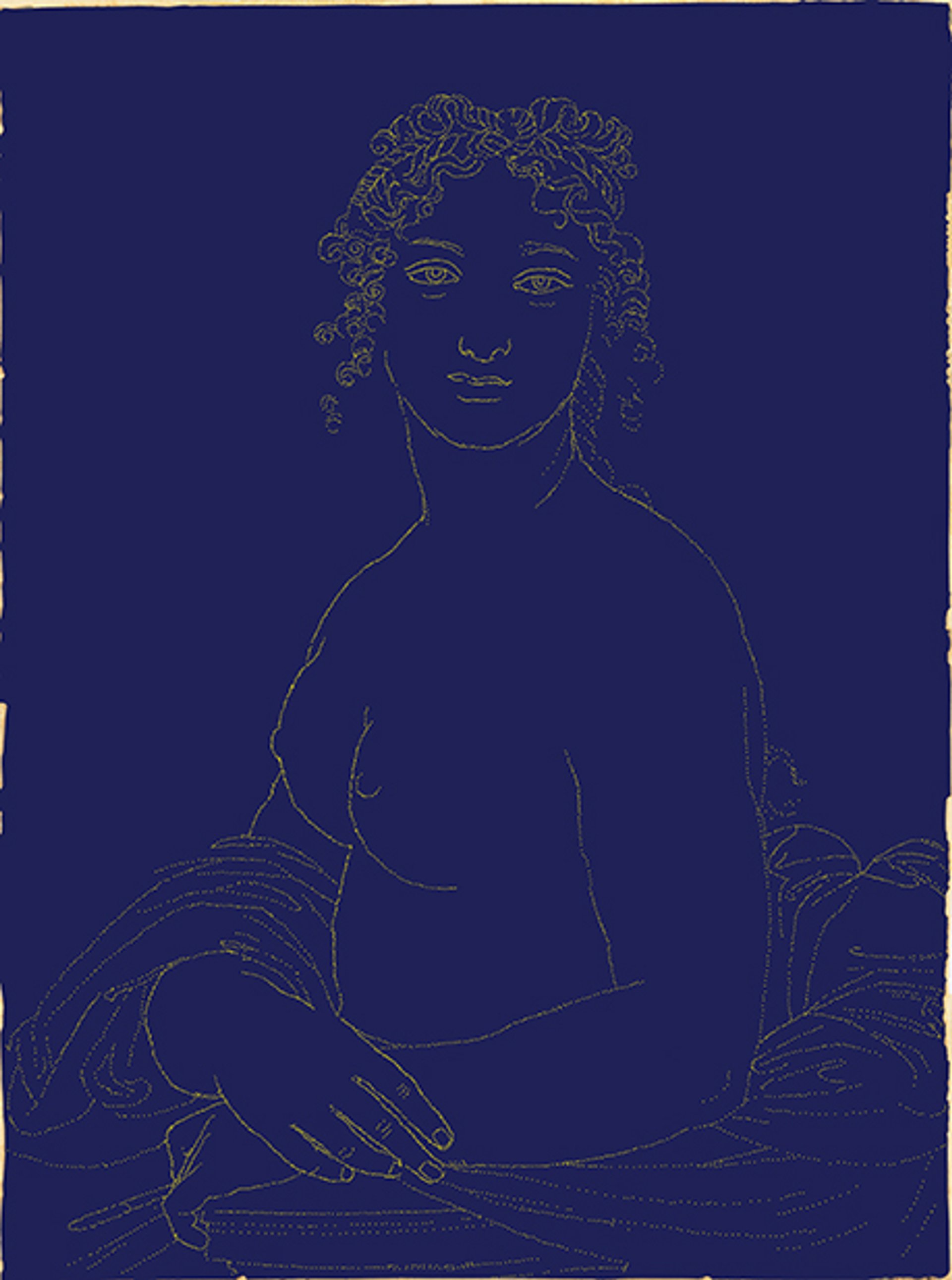

A light rendering of Mona Vanna's outline © Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France - Laurence Clivet

In the catalogue, Delieuvin describes the strange theories about this extraordinary figure, which combines feminine eroticism with a muscular physique. “This nude has become even more enigmatic than La Gioconda [Mona Lisa] herself,” he says. No reliable testimony can be traced regarding its genesis; there is only a notation in Salai’s post-mortem inventory of 1525, referring to a “meza nuda” among a dozen copies of Leonardo’s works. A pupil and lover of Leonardo, Salai was also the middleman who sold the collection to the King of France.

The work is actually a cartone (or cartoon): a full-scale preparatory drawing. Mottin reconstructed the meticulous contours of the pinholes, which were used to transfer the outlines of the design by rubbing in charcoal powder (spolvero), in preparation for an oil painting. The artist in fact made the transfer to a second cartoon, in order to protect the original one from the charcoal.

Infrared detail of Mona Vanna's fingers © Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France - Laurence Clivet

Since 1901, no scholar has recognised the hand of Leonardo in the work. But the laboratory’s findings tell another story. They show the traces of a fine drawing made with carboncino (charcoal), which “was widely abraded”, Mottin says. The sketch was highlighted with strokes of lead white, “an indication that this is not one of those cartoons destined to be thrown away after it has been used, but a ben finito drawing”. Another characteristic is its unusual size—77.5cm x 52cm—for which the artist had to paste two sheets of thick paper together. Some hatchings on the face are apparently drawn by a left-handed artist, which was the case with Leonardo. Like another of his cartoons, the portrait of Isabella d’Este in the Louvre, it was badly damaged and at one time was largely repainted with ink, covering and partially altering the original design.

Infrared detail of Mona Vanna's head © Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France - Laurence Clivet

The portrait is very similar in size to the Mona Lisa. Delieuvin believes that certain parts, like the seat or the right hand, point to the same artist. But a superimposition of both images shows significant differences. “This character is not a nude version of La Gioconda,” he says, “but you can see that the painter might have worked on both pieces at the same time.” Both authors discard the idea that the cartoon was used by Leonardo himself for a painting that has since disappeared. But a canvas from a private collection, apparently painted in the first decades of the 16th century, shows a striking correspondence with the spolvero points. This appealing work, on long-term loan to the Museo Ideale at Vinci—which could be by Salai or Francesco Melzi (another pupil and heir)—is now being shown next to the cartoon at Chantilly.

Carlo Antonio Procaccini's Flora (c.1600) © Academia Carrrara Bergame

So what should the Chantilly portrait be called? For Delieuvin, the most plausible hypothesis is that the artist designed an “idealised portrait”, common in the Renaissance: an antique deity rather than a person of the time. One painted variation, lent by the Carrara Academy of Bergamo, shows the sitter as Flora, the goddess of spring. Delieuvin points out that the intricate hairstyle is the same as that adorning the Capitoline Venus Pudica, with the artist “choosing to stress the sensuality and ambiguity of this ideal of female beauty”.

• The Nude Mona Lisa, Domaine de Chantilly, 1 June-6 October