The art historian Ben Street wants to demystify why and how we look at art in his new publication How To Enjoy Art: A Guide for Everyone. Street attempts to debunk the idea that enjoying paintings and works in other media require some sort of art historical insight. In the introduction, the author writes: “The idea that specialist historical knowledge is required to gain access to the meanings of works of art generates an unnecessary distance between an object and its potential viewer”. Street stresses how works are beset with data, including as dates, names and periods, as well reams of writing, such as explanatory texts emblazoned across museum walls. “Wherever we encounter it, art comes wrapped in words,” he says. His goal is to help the reader and viewer enhance their art-viewing experience through a handful of core strategies and skills, describing in essence how we are all capable of reacting instinctively to a work. In the extract below from a chapter Colour, Street describes how a section of painted wall from the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii spoke to the Abstract Expressionist Mark Rothko.

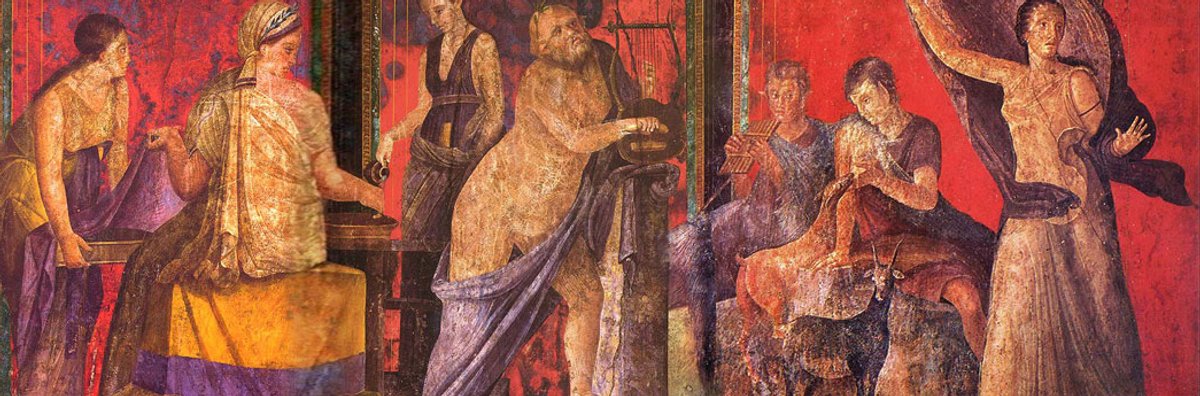

A section of fresco from the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii

The [Villa of the Mysteries] got its name from the famous sequence of wall paintings in one of its rooms, whose content and meaning has remained inscrutable, despite countless theories posited by generations of scholars and visitors. Many of these theories are preoccupied with interpreting the narrative content of the paintings, which means identifying specific characters or putting a figure’s curious gesture or pose into words. Attempts to ‘solve’ works of art like this one are commonplace both in academic art history and its appearances in popular culture. You might think of Dan Brown’s 2003 book The Da Vinci Code, which dramatises attempts to crack the hidden meanings of famous paintings. Artworks are treated in this way like crime scenes: given enough scrutiny and expertise, their secrets will suddenly be revealed; they will become obsolete, and we can move on to the next one.

But treating artworks as problems awaiting a solution means overlooking many of their essential features. Their physicality, for one, by which we mean their scale, their surface and how they were made. Their placement, for another: how they exist in and respond to a particular actual space. And finally, and perhaps most importantly, their flexibility: the fact that works of art don’t or can’t possess a single meaning that remains fixed for all time. Each passing year changes the potential meanings of artworks, since the meanings of works of art are generated by being looked at, and audiences, naturally, change. There is no knowing what the original inhabitants of the villa thought about these mysterious paintings. And if an ancient Roman guidebook were suddenly to be unearthed onsite, this would not give us the final word on what the paintings mean, but what they might have meant at a particular point in history to a particular person. What makes them art is that they have the capacity to welcome and withstand any number of possible responses. By nature, their meanings are slippery, resisting closure.

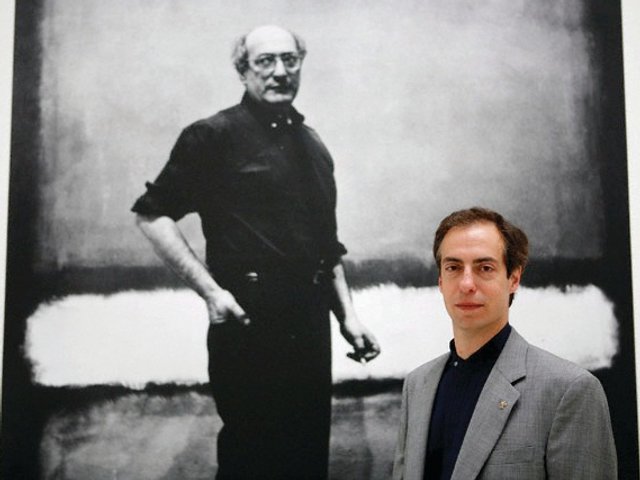

Rothko asserted the physicality of his work, demanding his paintings be shown without frames or glass and hung low to the ground

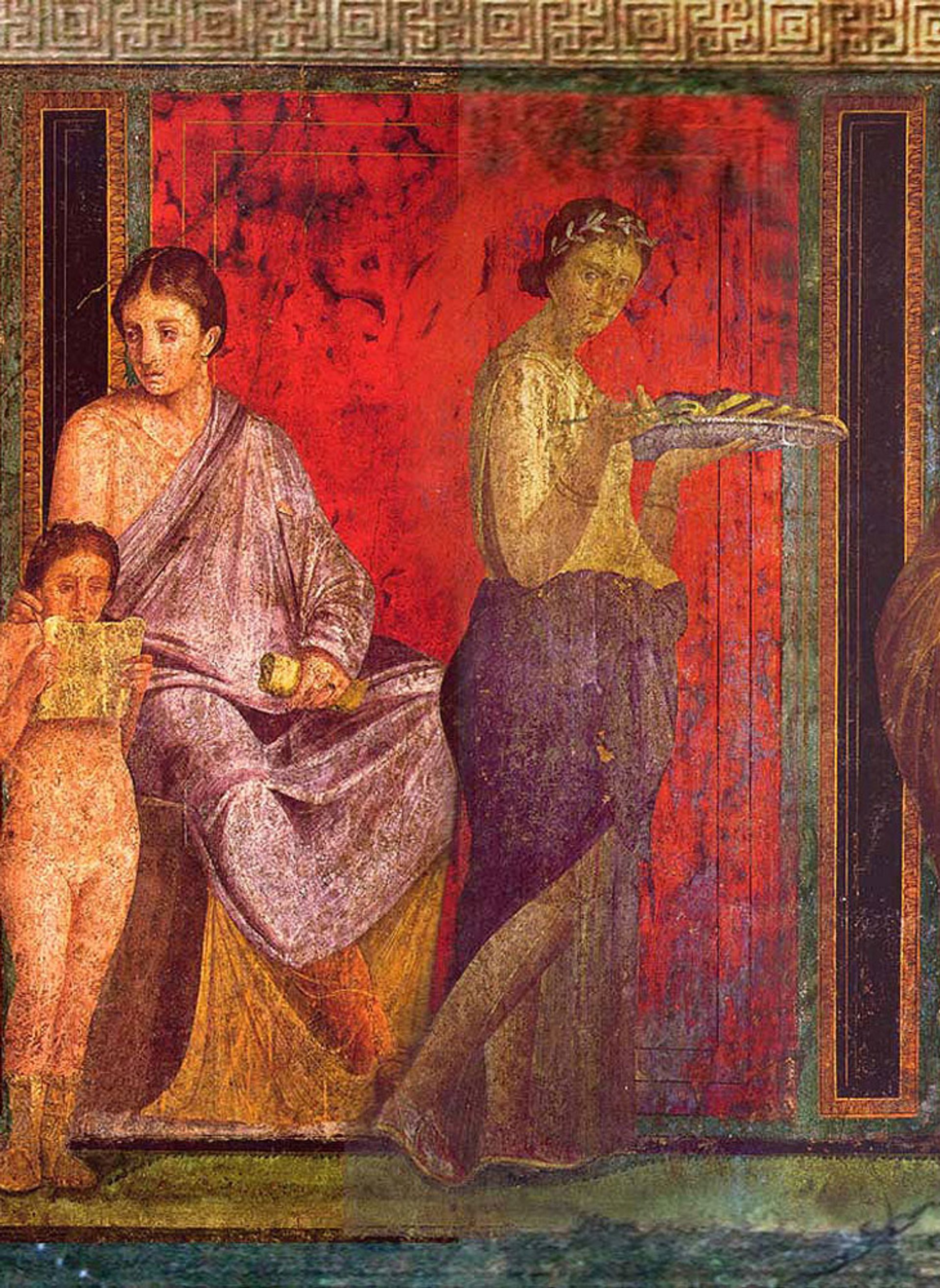

The Latvian-born American abstract painter Mark Rothko understood this. Visiting Pompeii in the late 1950s, he saw the Villa of the Mysteries frescoes as having the same kind of spirit as his own paintings. Anyone familiar with Rothko’s work will have no difficulty seeing the villa through the modern artist’s eyes: clearly it was the expanses of rich red behind the figures that Rothko found so captivating, given their resonance with his own work. What’s interesting here is that Rothko’s response is very much not about art-historical decoding. Instead, he recognises within these ancient images, made in a wildly different context to his own, a certain kind of expressive kinship. Rothko’s paintings, with their slabs of deep reds, blacks, greens and browns, attempt to conjure up certain emotional and spiritual states, which would, he hoped, resonate with a receptive viewer. Interestingly, Rothko also asserted the physicality of his own work, demanding his paintings be shown without frames or glass and hung low to the ground. He even encouraged viewers to stand about 18 inches from their surfaces in order to properly experience them. It’s worth trying that with other paintings, even non-abstract ones, if they’re large enough. At that distance, the edges of paintings recede into your peripheral vision, as do wall labels, other works of art and other people. What becomes evident is not the content of paintings, their narratives or subjects, but their specific presence as objects. It’s a little like standing face to face with another person at close range: after the initial awkwardness has passed, a more acute sense of them as a physical being emerges.

Detail of a fresco from the Villa of the Mysteries

Standing that close to a Rothko, security alarms notwithstanding, means that you are engulfed by, swamped by, his huge fields of rich colour. This might or might not have the desired effect. Many people are put off by this sort of grandiosity. Being put off by Rothko was, in fact, a starting point for many innovative ideas in modern art. But, regardless of one’s response, it remains of use in our thinking about colour in art, because Rothko evidently recognised that colour alone, without it needing to be translated into language or used to describe the visual world, might be able to speak to a spectator directly, in an immediate way, that cuts across levels of expertise, prior knowledge or experience. The hundreds of people who visit rooms of Rothko paintings in museums across the world and remain there, transfixed, moved, or overwhelmed, are testament enough to the artist’s understanding of how colour speaks. The fact that he found the same kind of effect in the ancient wall paintings of Pompeii might seem ahistorical—those frescoes aren’t abstract, after all, at least not in a conventional sense—but might also be seen as a profound moment of awareness: that the use of colour as an expressive effect is something that might be a core component of art whenever or wherever it might be made. It might even be part of the very definition of art itself.

• How To Enjoy Art: A Guide for Everyone, Ben Street, Yale University Press, 160pp, £14.99 (hb)