Hope You See Me as a Friend is the first exhibition in the UK by the artist Cem A, who is best known for the meme account @freeze_magazine. The exhibition, which was staged at the Barbican Centre, did not unfold in a conventional exhibition space but rather on the information screens across the space that would usually communicate information about the museum. @freeze_magazine has been making memes since 2019 with a reach of hundreds of thousands of people. The account has created hundreds of memes commenting upon the most pressing issues in the art world that conventional art criticism, artists and institutions often skirt around.

The Art Newspaper: What do you think makes memes—and more specifically, the ones that you create—so popular within the so-called art world?

Cem A: Memes blur the lines between art making and art criticism, which makes them interesting for the art world. Memes are also meant to evolve with trends. They are defined by the circulation of the image rather than the content of the image. (For instance, a painting of a meme does not carry the same potency as a digital meme that travels and evolves through the internet.) These qualities of memes make it possible for the @freeze_magazine social media accounts to reach hundreds of thousands of people per month, which is comparable to that of a museum, art fair or (actual) magazine.

What was the impetus for starting to use the meme as a material in your art making? Can you recall the first meme that you made and why you made it?

If I remember correctly, it was something making fun of Hans Ulrich Obrist’s Instagram project. The meme got a lot of positive reactions, which is what encouraged me to start @freeze_magazine. Reflecting on this period now, I realise that it coincided with my disillusionment with the London art world, giving me plenty of subject matter to work with.

"But is it art?" is a philosophical question that pops up whenever artists utilise materials found more commonly in everyday life—how would you answer this question in relation to your memes?

If concepts as sophisticated and as hard-to-grasp as Fluxus or relational aesthetics have been widely accepted as art movements, I have no hesitation in calling memes "art". However, my intention in this assertion is to recognise meme culture as an extension of visual arts while rejecting modern art terminology. A meme account can be seen both as an artwork, an exhibition, a performance or even as an institution in and of itself. Memes conform to none of these concepts.

I often use memes in my lectures to teach, their immediacy is very useful when introducing students to complicated ideas in critical theory. What potential do you think memes have? Can memes change anything?

Memes can be seen as a way of packaging visual content and cultural references in a metaphorical way. Therefore they carry a political potential too. I believe memes are especially potent to convey reformist messages rather than revolutionist ones.

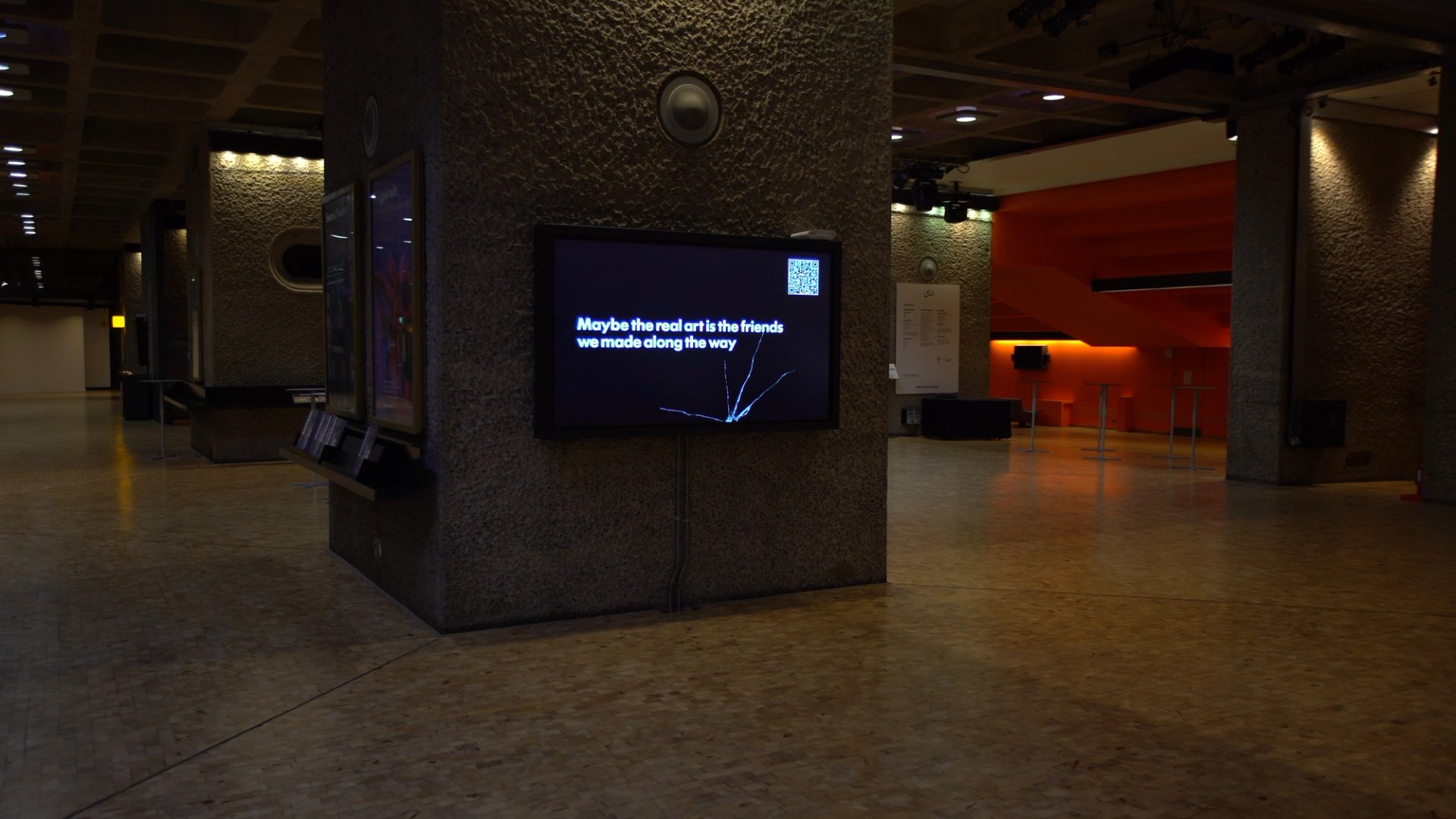

Why was it important for you to use the information screens at the Barbican as a way to display the memes in the exhibition?

Information screens occupy a space between the art and the institution. They are usually just a mundane and didactic aspect of an art gallery. I wanted to use this as an opportunity to intervene in the experience of visitors who are probably at the Barbican to see a concert, film or another exhibition.

An installation view of the exhibition Hope You See Me as a Friend at the Barbican Photo: © Andy Hui

I stood and watched people looking at the work and they seemed confused by the statements on the screen; the confusion often dissipated into laughter. The work has this ability to suck its audience in. Can you tell us a bit about the content of the pieces?

The statements all make references to memes in their content and structure. For instance, “The vibe is continuing to deteriorate” is a sentence you might see in a meme. Other references include, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, whose work has been attributed to Marcel Duchamp, or “Birds aren’t real”, a fake conspiracy theory that makes fun of conspiracy theories.

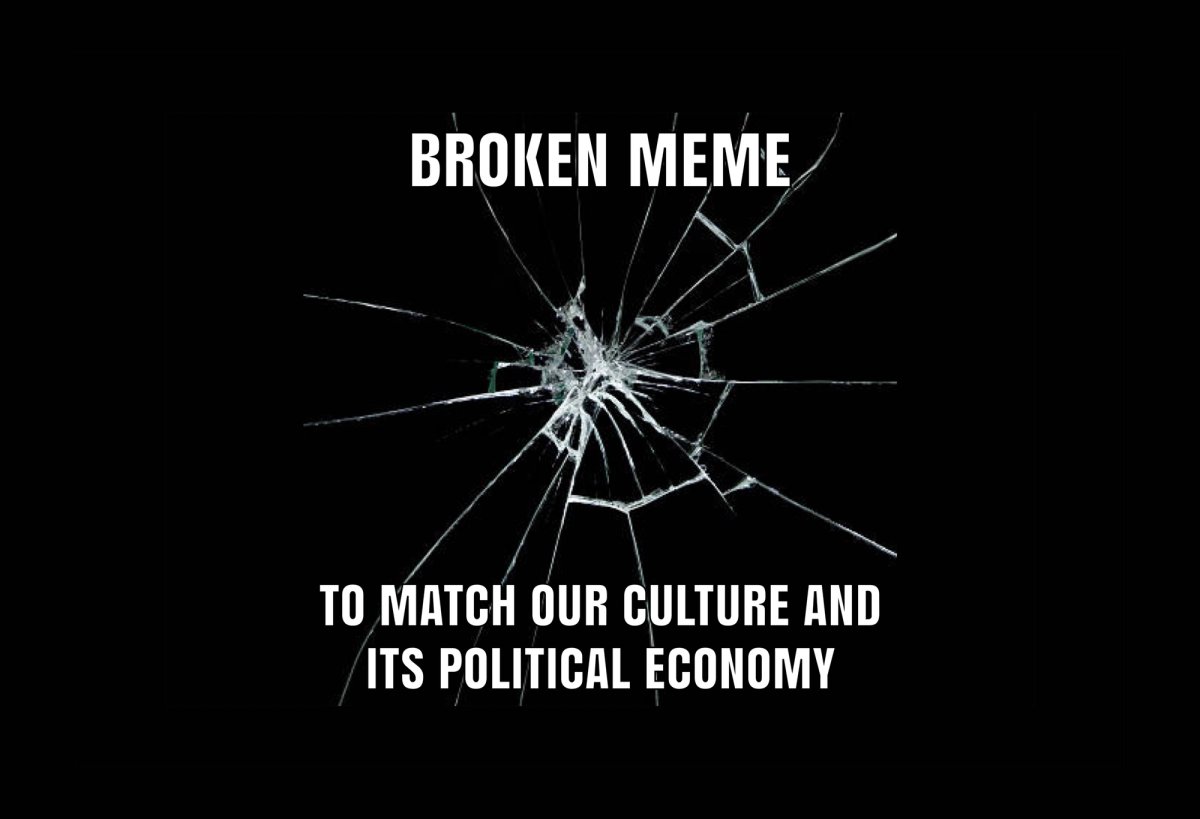

The screens at the Barbican appear to show a crack, akin to that of a cracked phone, which is jarring as it feels familiar but at the same time staged. Can you tell me a bit about this crack?

The crack motif originates from the crack on my phone, on which I make all of my memes. I like the idea of connecting with an audience by placing them on the other side of the crack. Also, if the crack is successful at “fooling” people, it also puts them in an odd position. They might ask: Is this supposed to be an artwork? Was there a protest in the building? Should they tell a member of staff? Visitors are conditioned to accept anything placed in a gallery as artwork, even if they doubt its validity, like this funny incident at San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art. They are scared to ask the staff if something is an artwork. This is a problematic element of Western exhibition making. I hope running through these questions encourages the visitors to actively engage with the concert, film or exhibition they intended to see at the Barbican.

• Frank Wasser is an Irish artist and writer based in London