Walk down one of the bustling streets of Lingarajapuram, in the city of Bengaluru in southern India, and you will find a small shuttered shop. Inside, colourful cloths hang from floor to ceiling, each bearing the stories of women who have come here to embroider their experiences in stitches. Further in, you will find a swing for visitors to spend moments in solitary, soothing motion—a brief way to escape the cacophony of life outside.

Indu Antony, a former doctor who decided to pursue a career as an artist, opened the space in February. She called it Namma Katte, or “My Space”. The project is funded by London’s Wellcome Trust as part of its year-long Mindscapes initiative, a new programme that addresses the global mental health crisis by marrying scientific research with art.

In addition to artist residencies in six cities around the world, Mindscapes exhibitions are taking place at the Library Foundation of Los Angeles and Los Angeles Public Library (until 6 November), the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo (until 6 November) and Gropius Bau, Berlin (until 23 January 2023), with events also scheduled at the Hamwe Festival in Kigali, Rwanda (9-13 November). The Brooklyn Museum, New York, meanwhile, hosted an exhibition that closed in September.

Mental health is a growing and insistent public health crisis. The pandemic led to a 25% increase in depression and anxiety, according to the World Health Organisation. Aligning with the World Health Summit in Berlin (16-18 October) and World Mental Health Day (10 October), the Mindscapes initiative seeks to deepen understanding of a complex crisis that is felt globally but has widely varying individual and cultural challenges.

Talking about mental health is considered to be a certain privilegeIndu Antony

“Talking about mental health is considered to be a certain privilege—most people in India don’t have time and space to sit and think deeply about themselves,” Antony says. “Even creating places of rest, the simple act of inviting something to sit and do nothing, can be such a luxurious, radical idea in our part of the world.” Her work will also be shown at her studio in Cooke Town, near Lingarajapuram, before a solo exhibition at the Museum of Art and Photography in Bengaluru, India, in March 2023.

Antony created Namma Katte to respond directly to the local need to create places outside the domestic environment for women to freely express themselves. “I remember hearing stories with messages like ‘women should be strong’, which I found to be very superficial,” she says. “I had to keep asking them: What does it mean for you to hold yourself in this way? Where is your pain coming from? Why do you express yourself like this?”

Antony encouraged the women she met to explore their feelings more deeply. “We started with ten stories. Today, we have 520 stories, many of which talk about extremely intimate things,” she says. “I don’t think the women we spoke to would have been so open without Namma Katte.”

But is it really possible to tackle such a huge and nuanced subject in a global context? “That is exactly the challenge for the Mindscapes project,” says Mami Kataoka, the director of the Mori Art Museum. As the pandemic hit Japan in 2020, suicide rates soared for the first time in more than a decade. “There are cultural specificities and group pressures in every region,” Kataoka says. “But some things are fundamental and universal to all of humanity.”

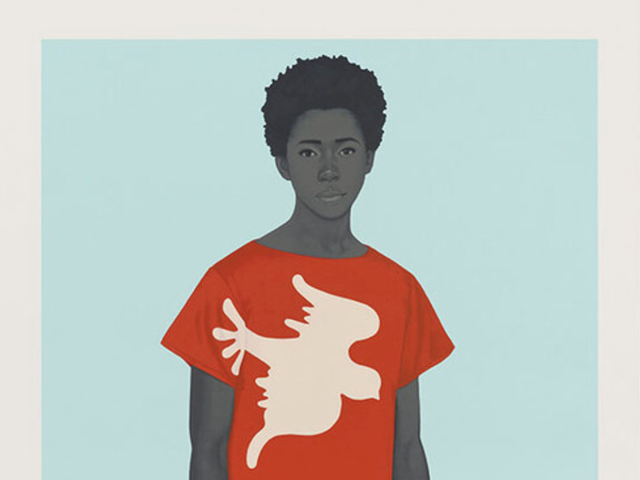

Guadelupe Maravilla’s exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum this summer. The artist describes his sculptures as “healing machines”. Photo: Danny Perez

The reality of the current crisis depends as much on understanding individual lived experiences as it does analysing scientific data, Kataoka says. She cites Guadalupe Maravilla, a Mindscapes resident artist in New York, who presented an exhibition of his ongoing project Disease Throwers at the Brooklyn Museum this summer. The artist’s sculptures are “healing machines,” he says. They explore his childhood experiences as an undocumented immigrant who arrived in the US from El Salvador, as well as a diagnosis of colon cancer when a young adult.

“Guadalupe’s exhibition really relates to the experience of cancer treatments,” says Rebecca Jacobs, Mindscapes’ New York curatorial research fellow. “As we know, chemotherapy and radiation are hard on the body. He says, sometimes, we need alternative forms of medicine to heal from Western medicine. As part of the exhibition, he would perform healing ceremonies in the museum.”

Balancing the local and the universal

Danielle Olsen, the head of cultural partnerships at Wellcome, and Mindscapes’ curatorial leader, says: “I’m not a mental health researcher but, as an extremely interested outsider, one of the challenges for this field of enquiry is how to balance an understanding and respect for the uniqueness of each human life with an understanding of what large datasets can reveal about populations at scale.”

Ultimately, Mindscapes exposes that communities across the world are bound more by similarities than differences. The project of Christine Wong Yap, a Mindscapes artist in residence at large, highlights the way mental health is bound up with what Olsen refers to as the “universal human need” to belong. She organised workshops with teenagers in New York, community groups in Berlin and Bengaluru and elderly people in Tokyo, asking each group to speak about how they create a sense of belonging in their lives. Responses were compiled into books which can be used as a mental health resource.

Mental health might be a multi-faceted issue, but one of the overriding needs Wong Yap picked up on was the desire for a place where people “can feel free from being judged”. The takeaway for institutions is how they might provide such places for the public—on a large scale and in the long term.