Hurvin Anderson often speaks about being in one place while thinking of another. As this sumptuous volume reveals, it’s a sensation the British painter has explored for 25 years, through sensuous, open-ended images that slip between figuration and abstraction. In his exuberant canvases and works on paper, themes of emigration, citizenship and identity shift in and out of focus, never quite willing to be pinned down. From the nostalgic interiors of Birmingham’s Black barbershops to the verdant landscapes of Jamaica, his art, shaped by an immersion in both British and Afro-Caribbean culture, interrogates places where history and memory collide.

This, Anderson’s first major monograph, covers his entire oeuvre, from the swimming pool paintings made soon after leaving the Royal College of Art in the late 1990s, to his recent Jamaican hotel series, inspired by abandoned buildings he discovered in Oracabessa. Flipping through its pages, you see he is a bold colourist, saturating works with the vivid hues of the Caribbean, yet tempering his palette with a British urban murkiness. When it comes to discussing his practice, however, Anderson can be coy, preferring to let the paintings do the talking. Rizzoli has ostensibly taken his lead by including more than 200 high-quality colour illustrations (including previously unpublished images from the artist’s archive), yet commissioning just a single essay by the art historian and curator Catherine Lampert, which follows Yale Center for British Art director Courtney J. Martin’s brief but lively foreword recalling an early encounter with the artist.

The youngest of eight siblings, Anderson is the only member of his immediate family not born in Jamaica, from where his parents emigrated in the early 1960s. No wonder, then, that his art so often conveys a sense of being caught between two worlds. This was amplified during a 2002 residency in Trinidad: “I was the Englishman, but I was also the Jamaican,” he said. “You could kind of drift back and forwards between these identities.” His paintings from this period are characterised by a sense of separation, as Lampert writes of the brooding Country Club: Chicken Wire (2008), which depicts a well-tended tennis court seen through a mesh fence: “its surface covered in repeated, sun-reflecting hexagonal shapes, tends to induce in the viewer an immediate sense of exclusion and unease”.

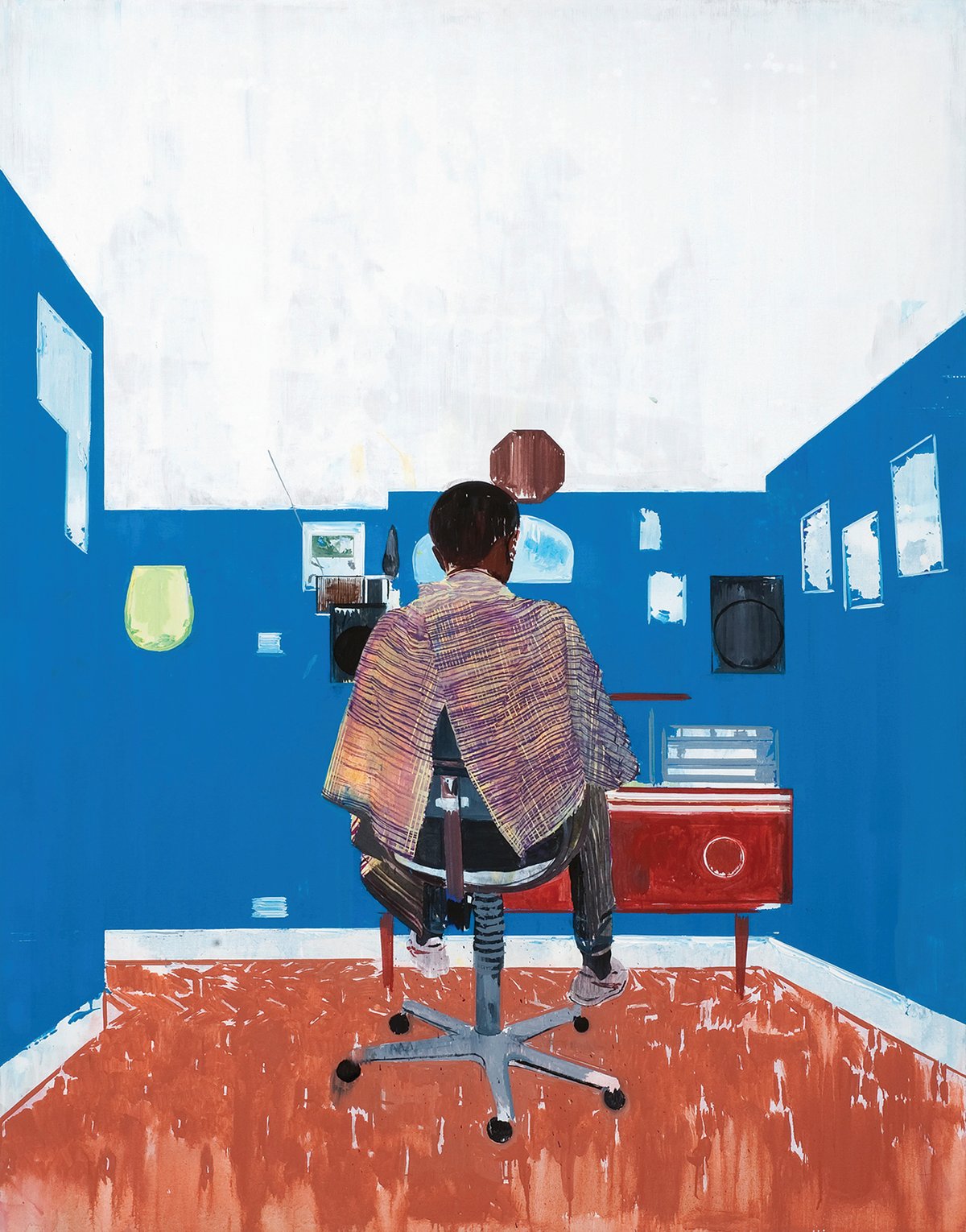

To Anderson, the barbershop space felt like a little piece of the Caribbean

Also striking is the artist’s penchant for working serially, repeatedly returning to a subject until it is exhausted. Take the barbershop paintings, which brought his work to prominence when they were displayed at Tate Britain in 2009. This series, which is the focus of a major retrospective at The Hepworth Wakefield next year, began with the bright blue interior of Peter Brown’s barbershop, a gathering space for Anderson’s father and his friends in the attic of the proprietor’s suburban home. To Anderson, this space felt like a little piece of the Caribbean and the photographs he took there spawned numerous paintings. Some show a client having his hair cut, while others focus on the intimate space devoid of people. Related works examine the barber’s paraphernalia, posters stuck to the walls, or the room’s geometry; several are deconstructed to the point of pure abstraction.

For Anderson, the barbershop series “bears the stamp of political, economic and social history”, and led him to paint Is it OK to be Black? (2015-16), commissioned for the Arts Council Collection’s 70th anniversary. Speaking overtly to questions of Black identity, it depicts an assortment of posters of influential personalities tacked to the barber’s mirror, from Martin Luther King and Malcolm X to Olympic athlete Carl Lewis and Muhammad Ali. Defined more abstractly, the treatment of these latter figures suggests a certain instability—a quality that pervades so many of the works reproduced in this book.

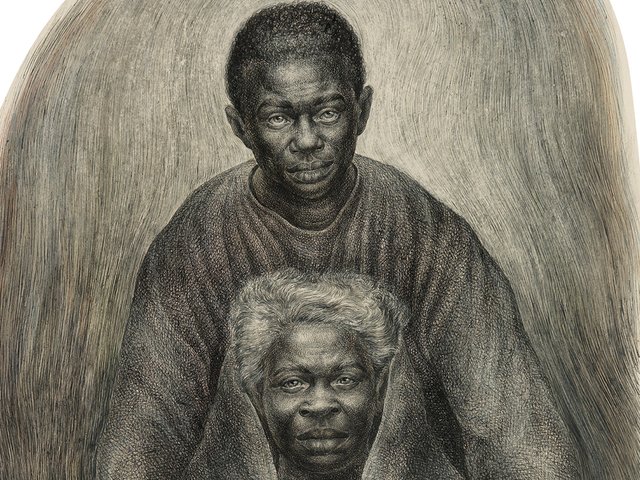

Lampert’s considered reading of Anderson’s practice is rigorously researched and laden with insights drawn from her close observation of his work and correspondence with the artist. Technical detail and analysis are deftly balanced with socio-historical context, biography and evocative descriptions. “At one moment,” she writes, “he seems to go down a route that relishes pictorial flatness, and the static quality of photography; on other occasions, or even in the same painting, he revels in the fluid weather-like potential of paint, as puddles, as blobs on the canvas-windowpane surface, or as windscreen-like washes across ‘empty’ space.”

While Lampert’s engaging overview is informative, if necessarily discursive, the absence of other essays exploring specific aspects of Anderson’s multifaceted approach is curious; for instance, a quote from Eddie Chambers, professor of art history at the University of Texas, whets the appetite for a scholarly Black perspective. In its stead, an illustrated chronology of the artist’s life and career is accompanied by 15 poems by Roger Robinson, the British writer and musician. These sensitive reflections on Anderson’s themes offer alternative ways to think about the work of this remarkable painter, perhaps revealing more about the way his enigmatic images operate than any conventional text.

• Hurvin Anderson, by Catherine Lampert, Roger Robinson and Courtney J. Martin. Published by Rizzoli, 320pp, 210 colour illustrations, £55/$75 (hb), published UK/US 6 September/25 October