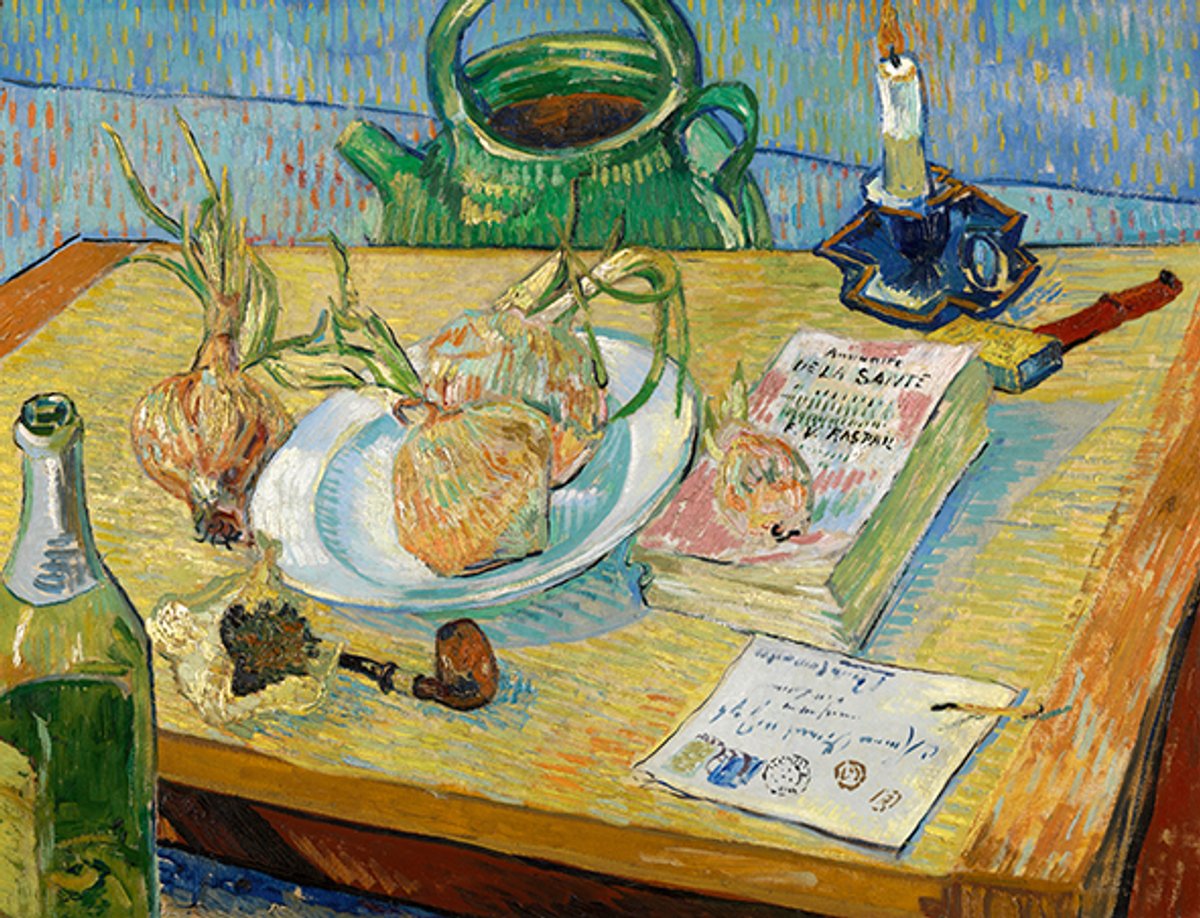

Still Life with a Plate of Onions (January 1889) is a highly personal painting, reflecting Van Gogh’s life after the crisis with Gauguin in Arles. Vincent had mutilated his ear just before Christmas 1888, after which he was quickly hospitalised. On being discharged on 7 January, he was impatient to pick up his paintbrushes.

That evening he wrote to his brother Theo: “I’m going to get back to work tomorrow, I’ll begin by doing one or two still lifes to get back into the way of painting.” Still Life with a Plate of Onions was one of the first pictures that he completed, a few days later. It was probably done in his modest kitchen.

After returning from two weeks in hospital, Vincent naturally derived great pleasure from his everyday possessions in his very own home. In Still life with a Plate of Onions his trusty pipe and packet of tobacco are at the front, along with a handy matchbox. The lit candle is at the ready—for lighting his pipe, for reading or for melting the adjacent red sealing wax required on registered letters. Lying on the letter is a burnt match or fire taper.

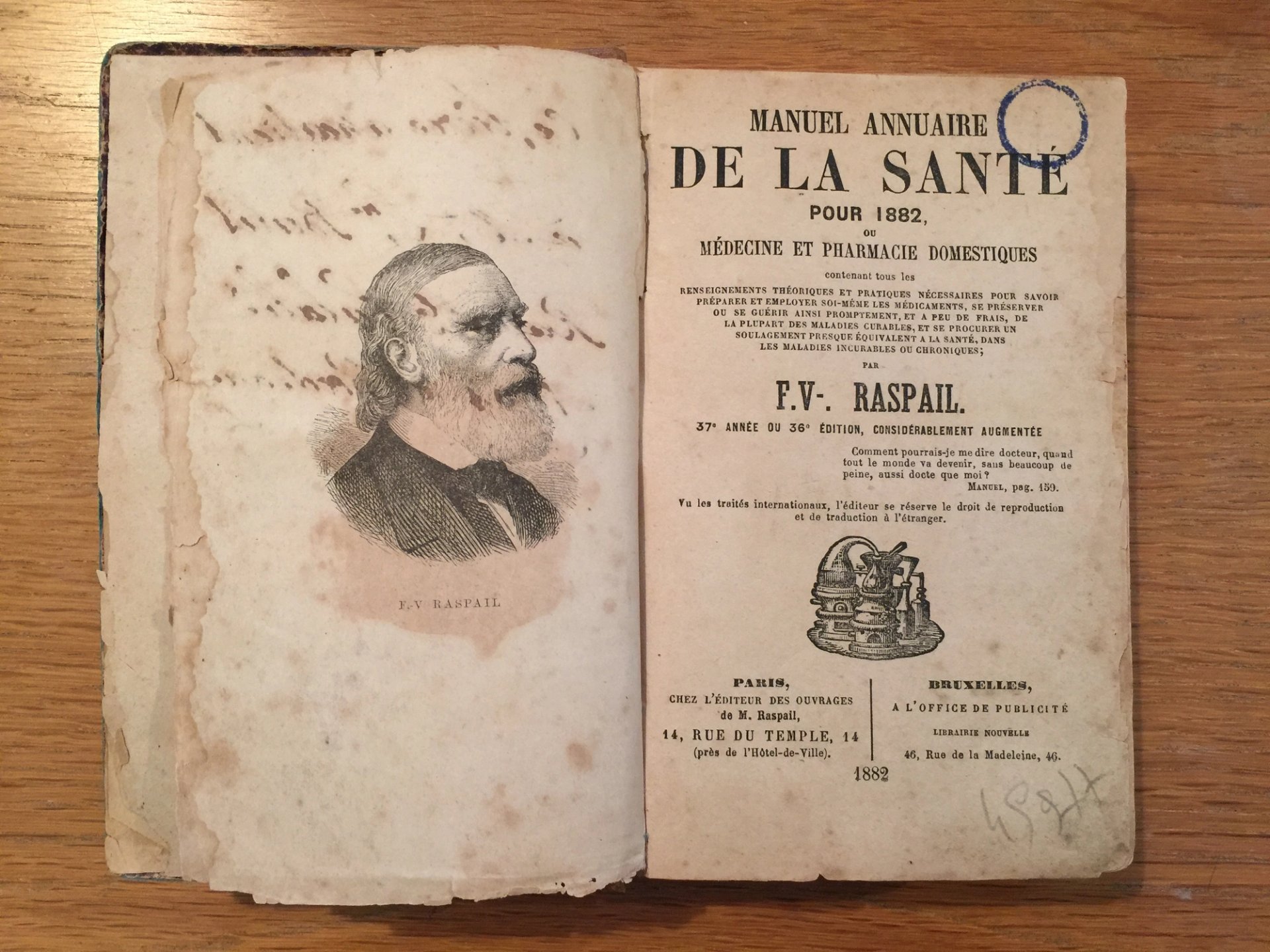

The book is a well-thumbed paperback copy of François Raspail’s Manuel Annuaire de la Santé, a popular 19th century guide for home medication. Having endured a mental attack and a serious wound, Vincent must have been seeking remedies. At the time he also suffered from insomnia, and was following a recommended cure from Raspail’s manual.

F.V. Raspail’s Manuel Annuaire de la Santé (1882 edition)

In the foreground of the still life stands an open bottle. The silver-foil top suggests that it is absinthe, although it is unclear whether the bottle is full or empty. At the back is a green water jug, useful for diluting absinthe. Gauguin later wrote that Van Gogh had thrown a glass of absinthe at him when they had had a row a few days before the ear incident.

Most curious are the onions, whose symbolism remains obscure. But they obviously had an important meaning for Van Gogh, since he also prominently included them, along with his beloved pipe and tobacco, in the painting of his chair, which was completed a few days after the still life.

Van Gogh’s Chair (December 1888-January 1889)

Credit: National Gallery, London

Even the furniture remains mysterious in Still Life with a Plate of Onions. At first glance the wooden surface with the assorted objects appears to be a table top, but looking more closely it could be a board—perhaps a drawing board, a portable table-top writing desk or even a large kitchen chopping board. And what are the water pitcher and absinthe bottle standing on—could they be benches? As with quite a number of Van Gogh’s Arles paintings, the perspective is deliberately slightly askew.

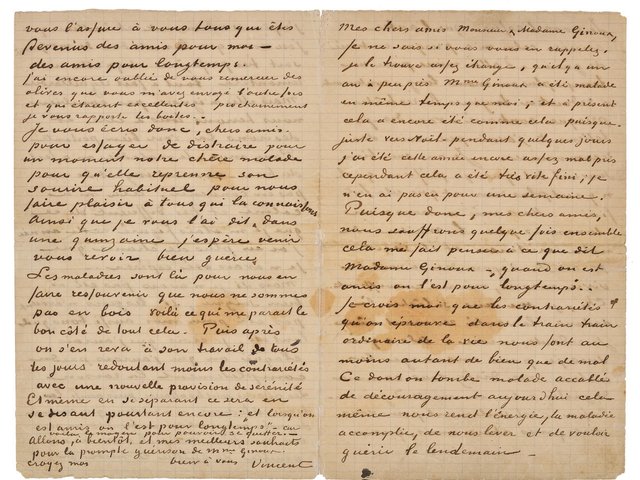

But the most intriguing object in Van Gogh’s assemblage is the envelope, placed in the foreground. The envelope (presented upside down) is addressed in Theo’s handwriting to “Monsieur Vincent van Gogh” in Place Lamartine.

Clues on the envelope suggest that this is the letter with the cash allowance that Vincent had received on 23 December. A brown ‘R’ mark for recommandé (registered) and the blue 15 franc and light ochre 25 franc stamps making up the price of a registered letter suggest that it included cash. The number 67 refers to the Paris post office in Place des Abbesses, near Theo’s apartment, and the larger black double circle is the Abbesses postmark.

If it is indeed the letter that Vincent received on 23 December, then this is highly significant. Around six days earlier, Theo had become engaged to Jo Bonger, so the letter would then almost certainly have conveyed news of the impending marriage. And it was that very evening of 23 December that Vincent mutilated his ear.

Vincent may have feared that his brother’s engagement might threaten his regular allowance, which enabled him to make his career as an artist. If he had been delighted by the news, he would hardly have mutilated himself a few hours later.

Although it is likely that the envelope depicted is that of Theo’s letter of 23 December, its meaning in the still-life remains more elusive. Does its inclusion in the painting a month later mean that Vincent had come to accept Theo’s relationship? Or did he remain disturbed by the engagement?

Although Vincent later sent most of his Arles paintings to Theo in Paris, this was among the relatively few that he left behind in May 1889 when he moved to the asylum just outside Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Still Life with a Plate of Onions was given to his friends Joseph and Marie Ginoux, who ran the nearby Café de la Gare. They sold it in around 1896.

The still life was acquired in 1913 (for the equivalent of £1,300) by Helene Kröller-Müller, who later set up her museum in Otterlo. Although its contents clearly relate to Vincent’s state of mind after the ear incident, this highly personal painting still holds many secrets.

Other Van Gogh news:

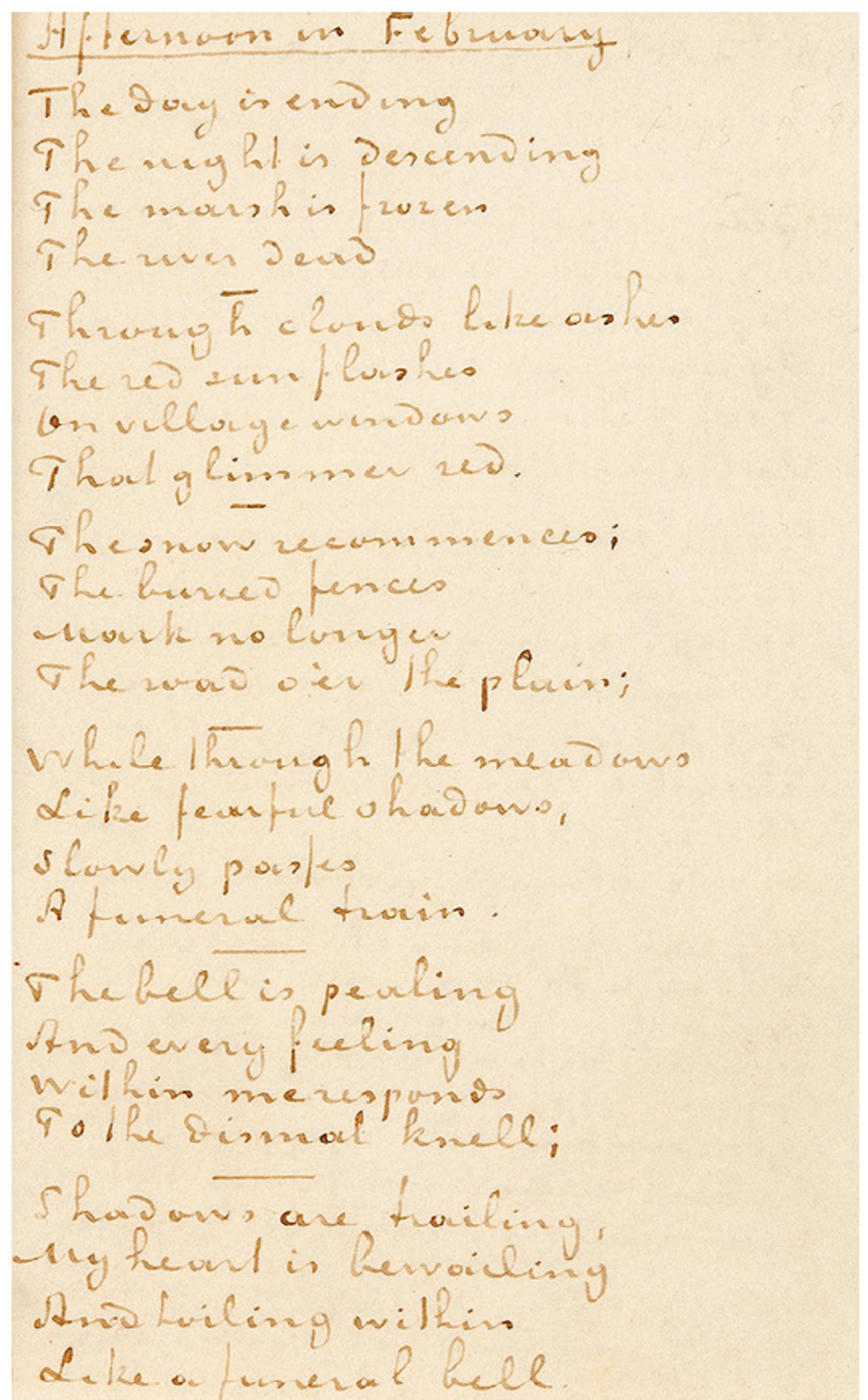

A tiny fragment of a Henry Wadsworth Longfellow poem copied out by Van Gogh has been doing the rounds, turning up at a string of recent auctions—in three countries. Afternoon in February was transcribed as part of six pages of various texts copied out by Vincent in an album belonging to Annie Slade-Jones, his landlord in Isleworth, west London, where he lodged in 1876 (when he was a teacher in England).

Van Gogh’s transcribed text of Longfellow’s Afternoon in February, the first six stanzas Credit: © courtesy of Aguttes, Neuilly-sur-Seine

The entire album came up for sale at Sotheby’s in 1976 and again a year later, but it remained unsold on both occasions. It eventually went for a relatively modest £550 in 1980. Tragically, the Van Gogh pages were later removed from the album and sliced into small sections, like the relics of a saint.

The 4in fragment with the first five stanzas of Longfellow’s Afternoon in February was later bought by the French company Aristophil, which was declared bankrupt in 2015. In 2018 the five-stanza fragment was put up for sale at Paris-based Aguttes, estimated at €20,000-€25,000, but it failed to sell. Eventually Aguttes sold it in April this year, for €14,300.

The fragment soon reappeared in Boston, with RR Auction, where on 10 August it was estimated at $40,000 (€39,000), but once again it failed to sell. For anyone still interested, it has crossed the Atlantic again. It is now in Spain, coming up at the Malaga-based International Autograph Auctions on 29 November 2022, estimated at €30,000-€40,000. One suspects this fragment of Vincent’s handwriting has been circulating among investors, not collectors.