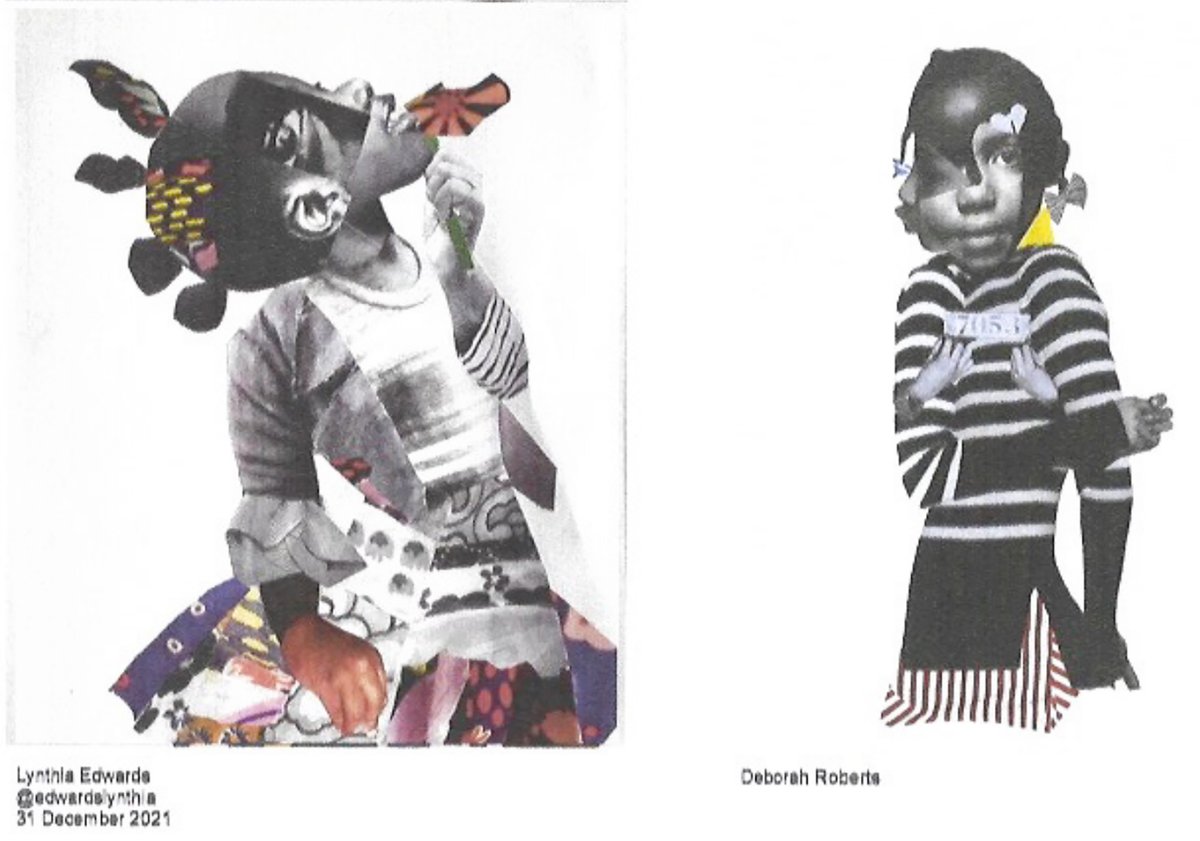

Last August, the artist Deborah Roberts, known internationally for her mixed media collages depicting Black children, filed a copyright infringement case against the artist Lynthia Edwards, her dealer Richard Beavers and his Brooklyn gallery. Attorneys for Roberts claimed that Edwards knowingly created works that are “substantially and confusingly similar” to their client’s, and through sales with Richard Beavers Gallery profited from the alleged infringement.

Lawyers for Beavers and Edwards are seeking to dismiss the Roberts suit, citing in documents filed yesterday (1 February) in US District Court in New York “numerous legal deficiencies” in the original complaint. They argue that Roberts’s claims rest on general stylistic similarities and underlying subject matter, which are not protected by copyright law.

"We’ve very bullish on our legal defence,” Maaren Shah, a lawyer for the Beavers and Edwards, says. “There is no precedent for copyright protections on an artistic style, let alone one like collage, which has such a long and rich history. What we have here is a clear case of an established artist with powerful galleries punching down to hurt the prospects and career of a longstanding member of the art community. We’re confident those facts come through clearly in our motion to dismiss.”

Lawyers for Roberts did not respond to requests for comment.

Edwards, an artist based in Birmingham, Alabama, portrays Black children, often girls, in handcrafted collages. Like Roberts, she constructs these assemblages using found photographs and other materials, but she sets them against colourful backgrounds, while Roberts typically opts for white or muted backgrounds. The figures in both artists’ works are conspicuous mixtures of patterns, forms, scales and perspectives. On her website, Edwards says her goal “is to honour and glorify the lives of Southern women”; Roberts has said that her works reflect an aim to “critically engage image-making in art history and pop-culture, and ultimately grapple with whatever power and authority these images have over the female figure”.

An amended complaint filed by Roberts’s lawyers in December 2022 features dozens of side-by-side comparisons of both artists’ collages. These, they say, illustrate specific elements that Edwards copied, thus infringing on Roberts’s “trade dress”—the distinctive look and feel of a product. The original complaint notes that these elements include high-contrast photographic fragments of facial features, hair, hands and feet, assembled in angular arrangements; colourful and patterned fabric swatches; and the focus on Black children or adolescents, individually and in small groupings, as subject matter.

In their most recent filing, lawyers for Edwards and Beavers argue that these elements are not unique to Roberts’s works and are not protectable by copyright law. Roberts, they add, is working in a long artistic tradition of collage and assemblage; the motion cites works by Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Faith Ringgold and Lorna Simpson, among others. “Roberts has no right—whether through copyright, trademark or otherwise—to try to pull the ladder up behind her after climbing a path that many artists have travelled before her,” the motion to dismiss states.

The motion for dismissal also addresses Roberts’s accusations that Edwards incorporated the same photographic source material as she did in her collages. The complaint alleges that both used, for instance, elements from the famous photograph of Rosa Parks, taken after she was arrested in 1955, as well as the fists of Muhammed Ali as photographed by Gordon Parks. “Roberts cannot establish infringement of an image that she does not own the copyrights to, and that she herself appropriated from another artist,” the lawyers for Edwards and Beavers write.

This week’s filing is the latest development in a years-long dispute between Roberts and Beavers concerning Edwards’s works. Roberts says that Beavers reached out to her in April 2020, asking her to allow her collages to be sold at his gallery in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighbourhood. According to her original complaint, the gallerist told Roberts that “so many of my clients have you on their wishlist of artists whose work they would like to acquire for their collections”. Roberts declined the request, after which, the complaint alleges, the gallery made arrangements with Edwards to create and sell her collages. The lawsuit also says that the defendants “aggressively marketed” the collages, including selling them at the same fairs that have exhibited Roberts’s work, including Expo Chicago and Untitled Miami Beach. Several consumers have allegedly mistaken Edwards’s collages for Roberts’s.

Attorneys for Edwards and Beavers write in the motion to dismiss that Roberts’s lawsuit merely aims to stifle market competition. Before filing suit, they say, Roberts pressured Beavers to stop representing Edwards, and left a voicemail for the dealer that said, in part: “I see that you’re representing that girl in...Alabama who’s ripping off my work. And I did get an attorney on her… she has no money. That’s the only reason I haven’t sued her. But I’m telling you right now, if she continues to show my work and do my work, I’m gonna make it public. Public. The New York Times. I don’t care what I have to do I’m gonna squash this.” Roberts, Beavers and Edwards’s lawyers allege, also asked patrons and collectors to boycott the gallery, and had it blocked from prestigious art fairs.

Speaking with Sighlines magazine, Roberts rejected the idea that her suit was filed to put down another artist. “This is not a frivolous claim,” she said. “I want everyone to be successful in the art world, especially young and emerging artists of colour. To say that I punch down at a younger artist is disingenuous. I don’t know [Edwards], but her work is being mistaken as mine.”

In the initial complaint, Roberts called for the court to order the impoundment and destruction of all of Edwards’s collages, though this request was rescinded in a subsequent, amended complaint. Roberts is seeking damages in excess of $1m.