An Italian author conducting research for a work of historical fiction about the life of Leonardo da Vinci has uncovered a document suggesting that Leonardo’s mother Caterina—whose background and biography have long been points of scholarly contention—may have been an enslaved person brought to Italy from the North Caucasus region of Eastern Europe, which today is a part of southern Russia.

In researching his novel Il Sorriso di Caterina, or Caterina’s Smile, Carlo Vecce, a professor at Orientale University in Naples and a Leonardo historian, unearthed a key document amidst the State Archives in Florence. Written by Leonardo’s father Piero da Vinci and dated November 1452—six months after Leonardo’s birth—the document records the emancipation of an enslaved Circassian woman named Caterina, whom Vecce believes to have been Leonardo’s mother.

“When I saw that document I couldn’t believe my eyes,” Vecce told NBC News. “I never gave much credit to the theory that she was a slave from abroad. So, I spent months trying to prove that the Caterina in that notary act was not Leonardo’s mother, but in the end all the documents I found went into that direction, and I surrendered to the evidence.”

“At the time many slaves were named Caterina, but this was the only liberation act of a slave named Caterina [that Piero da Vinci] wrote in all his long career,” the author continued. “Moreover, the document is full of small mistakes and oversights, a sign that perhaps he was nervous when he drafted it, because getting someone else’s slave pregnant was a crime.” This revelation would also mean that Leonardo was, by blood, only half-Italian.

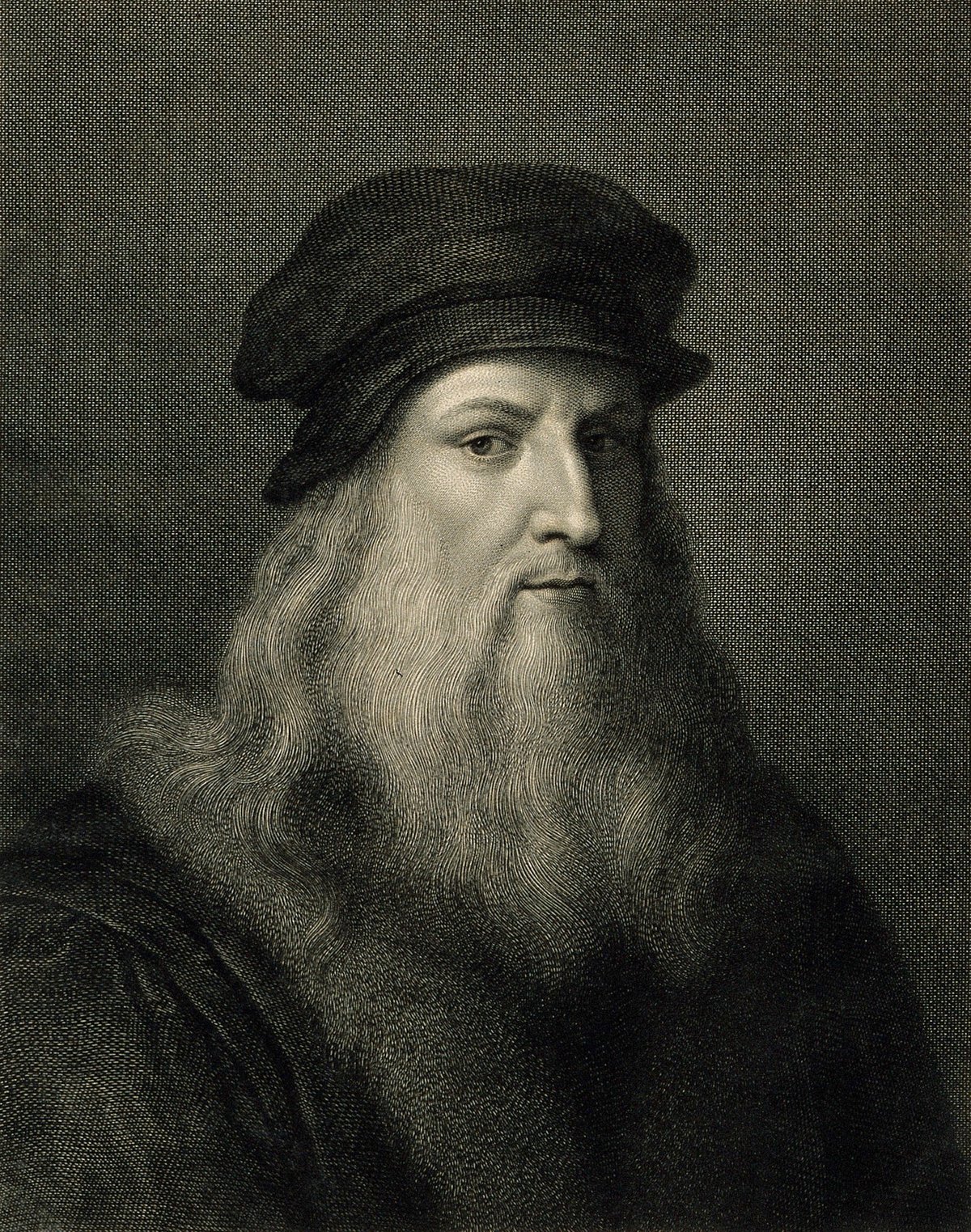

There are certain agreed-upon facts about the situation surrounding Leonardo’s birth—his father, Piero da Vinci, was a wealthy notary; he was born in 1452; his mother’s name was Caterina; and his parents were unmarried. (Had his parents been married at the time of his birth, Leonardo likely would’ve been expected to become a notary as well.) Other theories into Caterina’s life include that she may have been an enslaved Chinese woman or an orphaned teenager who lived in a local farmhouse. Piero da Vinci did eventually marry a woman from Florence, and he arranged for the formerly-enslaved Caterina to marry a local farmer, with whom she had four more children.

“Carlo Vecce is a fine scholar. His ‘fictionalised’ account needs the sensation of a slave mother,” the British art historian and Leonardo scholar Martin Kemp said in an interview with NBC. Kemp’s 2017 book, Mona Lisa: The People and the Painting, first posited the idea that Caterina had been a local orphan. “I still favour our ‘rural’ mother, who is a better fit, not least as the future wife of a local ‘farmer,’” he said, adding that “none of the stories are demonstrably proven.”

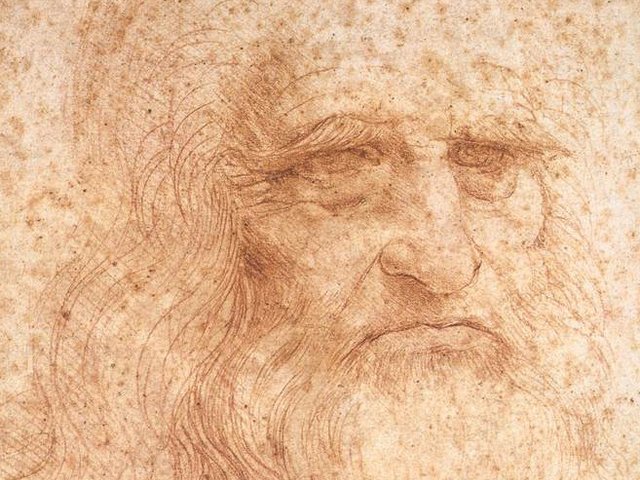

In an interview with The New York Times, Kemp also noted that the idea that Caterina had been enslaved was indeed “a conceivable model”, adding that the public’s fascination with Leonardo’s personal life is logical, as his biography remains largely mysterious despite the Renaissance artist having written “thousands and thousands” of pages on innumerable subjects throughout his lifetime. Paolo Galluzzi, a Leonardo expert and former director of the Galileo Museum in Florence, also told The Times that Vecce’s assertion is “a hypothesis” destined “to spur debate”, but that the research itself appears sound.

Vecce also noted that, while his new novel is a work of historical fiction, an academic article based on his findings is forthcoming.