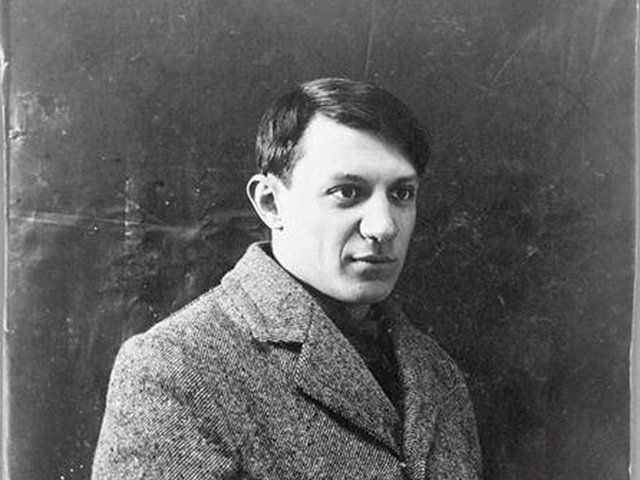

Anyone can consult the archives of the Paris police,” writes Annie Cohen-Solal at the start of her new book, Picasso the Foreigner. In the police stores, she finds a bulging file. “I have just encountered a suspect—a ‘foreigner’ who, on October 25, 1900, arrived in Paris for the first time, only to find himself trailed by the police a few months later.”

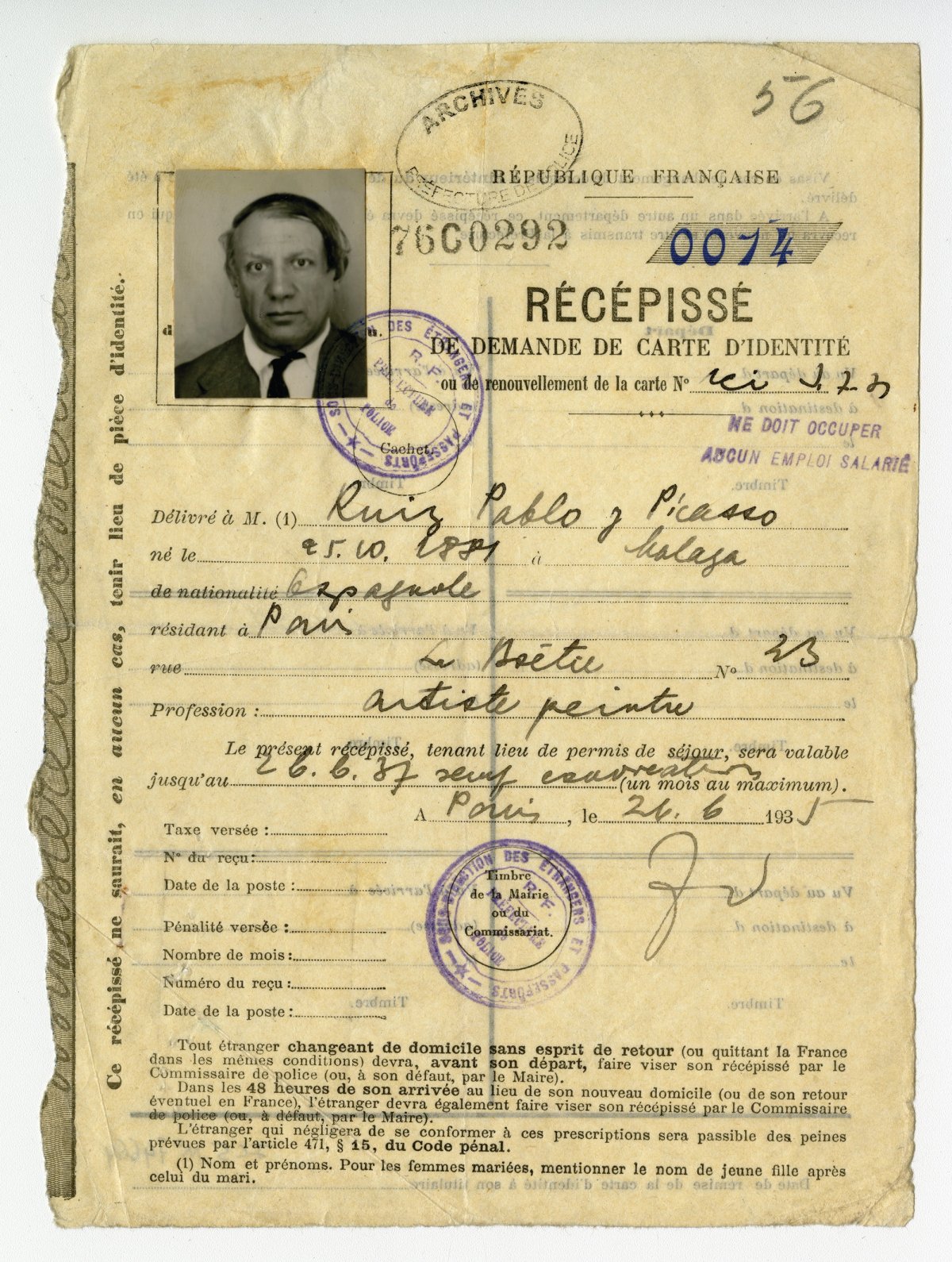

This foreigner’s case file would grow with every passing year for the rest of his life, writes Cohen-Solal, stuffed with reports, interrogation transcripts, residence permits, ID photos, fingerprints, rent receipts and naturalisation requests. The outsider in question is Pablo Picasso, who moved to Paris at the turn of the century, where, according to the author, he was soon labelled a threat to the state.

It was an expedition into Picasso’s micro-universe. I opened the thousands of letters his mother wrote himAnnie Cohen-Solal, author

“Discovering Picasso’s police files was actually a shock,” Cohen-Solal tells The Art Newspaper. “I could not believe how many times he had to go to the police station in order to get his carte d’identité d’étranger [ID papers required for a foreigner], which had to be updated every other year, with his fingerprints and ID pictures where he looked like an outlaw. In Picasso’s file, opened in 1901—when he was not yet 20 years old—the police officers wrote that he represented a threat to the country.”

Le Bateau-Lavoir in Montmartre, where Picasso stayed in the early 1900s © Roger-Viollet

She describes her research as a “scholarly treasure hunt” for which she cross-referenced data, travelling between the police and national archives, as well as the holdings at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. “This is how I was able to compare, for example, two police files at the same time: that of Picasso and that of Sante Geronimo Caserio, the young Italian anarchist baker who assassinated the French president in 1894,” she says. “Picasso was described as much more dangerous by the police than Caserio!”

Cohen-Solal realised that during his first 45 years in France, Picasso was stigmatised in three ways: as a foreigner, an anarchist and an avant-garde artist. “I also discovered how brilliantly Picasso handled this situation, by building very strong networks, both in France and in the Western world,” Cohen-Solal says. “For instance, the way he selected the very young Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler as his dealer is truly remarkable. It was a perfect choice. Kahnweiler understood his masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon [1907] before anyone else, and succeeded in promoting Picasso’s Cubist works from the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires to the United States before World War I, making him a rich man.”

The cover of Picasso’s extensive police file, which included reports, interrogation transcripts and fingerprints Courtesy Archives de la Préfecture de Police de Paris

The book focuses on the development of the avant-garde at the beginning of the 20th century, exploring, for instance, the career and impact of figures such as Kahnweiler. In Paris, Picasso was friendly with a group of immigrants who shared a multicultural background and understood exactly what Picasso was doing at the time of Cubism, Cohen-Solal adds, while no one in the French art establishment understood his innovations.

“These other expatriates are crucial to Picasso’s development,” Cohen-Solal says. “And so, I decided to explore who they were, how they thought, how they evolved, and how they interacted with Picasso. I described a fascinating collection of characters from Gertrude Stein, the poet from the US, to Kahnweiler and Vincenc Kramář, the scholar from Prague, and Carl Einstein, the critic and committed intellectual from Prussia.”

Picasso’s alienation also gives a new dimension to his art after 1914. Cohen-Solal argues that it has been difficult to make sense of the different aesthetic periods that Picasso went through, working as a set designer and surrealist artist, for example. “Why did Picasso start working as a theatre decorator for Sergei Diaghilev, the director of the Ballets Russes, in the first place? It is because after December 1914, when the stock of Kahnweiler was confiscated by the police—because Kahnweiler was a German citizen—Picasso had to find other professional contacts, ie niches where he could function and produce, protected from the French state.”

The book also delves into the intense relationship Picasso had with his mother, María Picasso López, through hundreds of affectionate missives between the two. “It was an expedition into Picasso’s micro-universe,” Cohen-Solal says. “I opened, one by one, the thousands of letters that his mother wrote him, noticing the way he opened them, some with his fingers, some with a knife, discovering that some were stained by paint, or by coffee.”

And what did Cohen-Solal think about the Spanish artist after spending years looking through all his documents? “Certainly I found Picasso much more compelling by the end of my research.”

• Picasso the Foreigner: An Artist in France, 1900-1973, Annie Cohen-Solal, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 608pp, $40 (hb)