By the time the Belgian artist James Ensor (1860-1949) turned 40 in 1900, he had already created most of the works that would make his name: paintings, drawings and prints that recast the world as a ghoulish, anarchic spectacle. His signature motifs of the mask and the skull, which eviscerate his figures in opposing ways, became what could be called his friends—reliable sources of inspiration, endlessly executed. But is there more to Ensor than this youthful fusion of Mardi Gras and Halloween? A show opening this month in Brussels at the Palais des Beaux-Arts (Bozar) argues, emphatically, yes.

James Ensor: Maestro comprises around 150 works and is part of Belgium’s year-long celebration of the 75th anniversary of Ensor’s death. It is curated by Xavier Tricot, the Belgian art historian who edited Ensor’s catalogue raisonné, James Ensor: The Complete Paintings. The word “maestro” refers to Ensor’s versatility across many media, Tricot says, but it also invokes the world of classical music: Ensor was not just an immensely talented visual artist, he was also a musician and composer. In emphasising Ensor’s works from the later decades of his career, the show positions his little-known 1911 ballet La Gamme d’Amour (the scale of love)—represented here with everything from the autograph score to Ensor’s own poster designs—as a singular manifestation of his talents.

Ensor was all but raised to be a chronicler of the grotesque. He spent nearly his whole life in Ostend, Belgium’s North Sea resort and carnival capital, where his shop-owning family sold carnival masks, along with puppets, seashells and other curious objects that made their way into his work. After studying art in Brussels, he began exhibiting in the early 1880s. By the decade’s end, his menacing, manic dreamscapes—which looked back to Netherlandish forebears like Hieronymus Bosch, and sideways to French caricaturists like Gustave Doré—were fixtures of the European avant-garde.

Icône. Portrait d’Eugène Demolder (1893), which demonstrates Ensor's move away from Impressionism, is on loan from the Groeningemuseum in Bruges. Photo: Hugo Maertens; Musea Brugge

The show will consider Ensor’s development away from a student interest in Impressionism into his early-onset mature style, with works like Icône. Portrait d’Eugène Demolder (1893) on loan from the Groeningemuseum, Bruges. The oil-and-pencil painting on panel stations a Netherlandish religious scene atop a demonic trio that features Ensor’s friend flanked by two figures ready for an Ostend carnival or a Boschian vision of hell. In 1905’s Pierrot and Skeletons, hell has taken centre stage, with the French pantomime figure, armed with a bloody knife, at the mercy of a crowd of costumed skeletons.

The conundrum with Ensor is how—or just when—to place him. Is he a proto-Modernist, holding up a funhouse mirror to the timelessness of the human condition? Or is he an actual Modernist, relying on his own inner mirror to report on the modern world’s advancing distortions? In emphasising La Gamme d’Amour, a spectacle Ensor devised for a group of dancers dressed as puppets, Tricot places him firmly in the Belle Époque, as a passionate Wagnerian trying to create his own Gesamtkunstwerk. Staged in Belgium a handful of times between 1917 and 1945, with a score that reminds Tricot of the music of French minimalist composer Erik Satie along with Frédéric Chopin, the six-part ballet was devised to have sets, costumes and advertising all created by Ensor. The exhibition will include a number of works associated with the various productions, such as a painted-photo tableau of an Ensoresque town square for use in staging the ballet’s second part. Outright musical imagery appears in a very late painting from 1938, The Flowering Clarinet, whose loose brushwork is a signature of Ensor’s final decades, Tricot says.

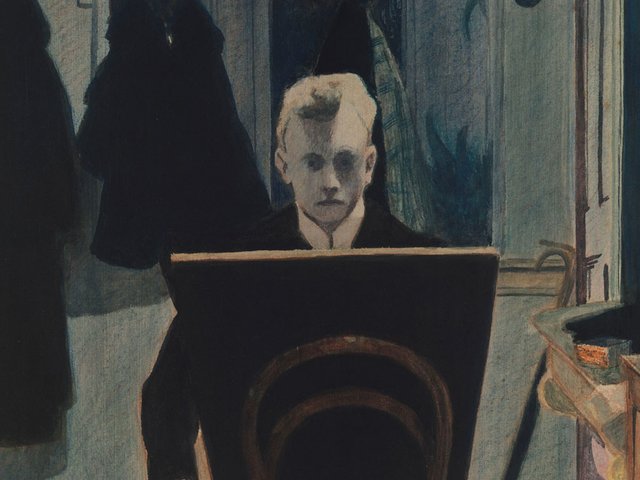

James Ensor surrounded by masks © Bozar Archives - Brussels

Though initially a scandalous bad boy, Ensor was already well on his way to becoming a figure of Belgian reverence before the First World War. In 1929, when he was made a Baron by King Albert, the then recently opened Bozar held a mammoth retrospective to honour the artist, including the first public viewing of his 8ft-wide mock-religious masterpiece, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 (1888). Too controversial to show until then, it later found its way to the US in 1987, becoming a signature work of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

Tricot includes a number of archival photographs of the 1929 retrospective. One documents a view of the painting’s original Brussels display. Another is a tongue-in-cheek portrait of the white-haired artist-baron, photographed with museum staff dressed as Ensor figures come to life, called James Ensor Surrounded by Masks.

• James Ensor: Maestro, Palais des Beaux-Arts (Bozar), Brussels, 29 February-23 June

Ensor's Roses (1892) will be on show at the Mu.Zee in Ostend Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België,Brussel. Photo : J. Geleyns

James Ensor 75th anniversary exhibitions

Rose, Rose, Rose à mes yeux: James Ensor and Still Life in Belgium from 1830 to 1930, Mu.Zee, Ostend, until 14 April

James Ensor: Inspired by Brussels, KBR, Brussels, 22 February-2 June

James Ensor: Self-Portraits, James Ensorhuis, Ostend, 21 March-16 June

James Ensor: Maestro, Palais des Beaux-Arts (Bozar), Brussels, 29 February-23 June

Ostend, Ensor’s Imaginary Paradise, Venetiaanse Gaanderijen, Ostend, 29 June-27 October

James Ensor: Satire, Parody, Pastiche, James Ensorhuis, Ostend, 19 September-12 January 2025

James Ensor’s Search for Light, Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp, 28 September-5 January 2025

James Ensor: In Your Wildest Dreams, Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA), 28 September-18 January 2025

Masquerade, Makeup and Ensor, MoMu—Fashion Museum Antwerp, 28 September-2 February 2025

• For more exhibitions and events, see ensor2024.be