For some six centuries, the immense baptismal font at Siena's Battistero di San Giovanni, located just behind the Tuscan city's zebra-striped Duomo, has been put to regular use in the baptising of local newborns. Art historians have also made much of the 6.5m-high structure. A cupola-topped greatest-hits of the Renaissance completed between 1417 and 1431, it is decorated with major works by Lorenzo Ghiberti and Donatello, the leading sculptors of Quattrocento Florence and pioneers in the application of perspective.

A hexagonal marble basin mounted with gilded-bronze reliefs depicting the life of John the Baptist, it also displays bronze statues, enamel bands and a marble tabernacle. By our own century, time and humidity had more than taken their toll on these treasures. The font was not only dirty—the once golden bronze was looking almost black—but actually unstable. Now, after a three-year restoration in both Siena and Florence, the reassembled font will be unveiled to the public today.

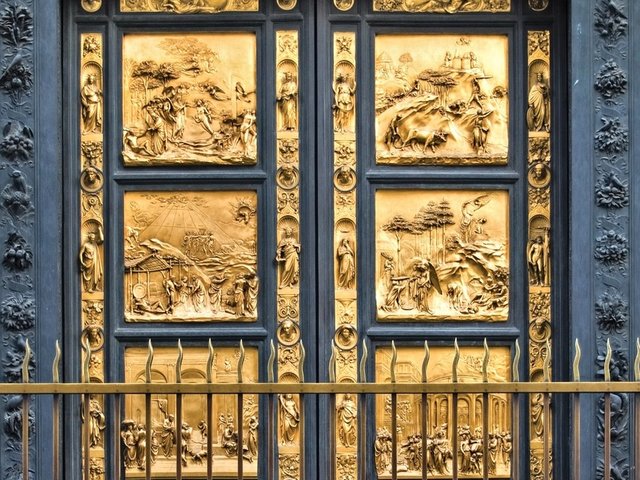

The metal elements were taken to Florence’s Opificio delle Pietre Dure (OPD), one of the world’s leading centres of art restoration, which had worked on Ghiberti’s bronze doors for the Florence Baptistry in the early 2000s. The stone elements and structural components were treated in situ by experts from the Opera della Metropolitana di Siena, which manages many of the city’s artistic treasures and—in an earlier incarnation—actually commissioned the font for the 14th-century baptistry building.

The baptismal font before the restoration Photo: © Luca Betti

High-tech met low-tech on the project. In Siena, gaps in the marble were patched with 3-D printed resin. Meanwhile over in Florence, cleaning corrosion and grime off the metal required the use of everything from state-of-the art lasers to real porcupine quills. “We use the quills because they’re very delicate,” says the OPD’s Laura Speranza. “You can’t go into crevices with a metal tool, for example, because it might damage the bronze.”

Though not imperative to keep the font upright, the cleaning of the relief panels is certainly the most eye-catching aspect of the restoration. Ghiberti's The Baptism of Christ, with its expansive cloud of attending angels, is now mysterious as well as elegant. And Donatello’s Feast of Herod, in which details of St. John's gruesome beheading are placed at either end of a perspectival sequence, is now a pristine interplay of archways and horror.

Lorenzo Ghiberti"s Baptism of Christ after the restoration Photo: © OPD. Cristian Ceccanti

Francesco Caglioti, the Italian art historian who curated the landmark Donatello exhibition in Florence in 2022, does not mince words about the font’s status in the history of European art. “There is no baptismal font in Western civilisation that is more important,” he says

Many works of art of this caliber are moved to more stable, climate-controlled locations, but the restored font is set to stay put—and return to use. Neville Rowley, the curator of early Italian art at Berlin's Bode Museum and the curator of the German version of the Donatello show, thinks that is all for the best. Rather than isolated but protected in a museum, the font is “still in context,” he says. “And that’s extremely precious.”

The baptismal font after the restoration Photo: © Bruno Bruchi

Art historians and other experts will weigh in on the restoration at the end of the year, when Siena will host a conference addressing its scholarly and technological implications. Caglioti, who says he is of the opinion that the font is even more closely related to Donatello than previously thought, hopes to attend.

A professor at Pisa’s Scuola Normale Superiore, Caglioti believes that a deep friendship between Donatello and Siena’s own Jacopo della Quercia, the sculptor who is responsible for the font’s stonework, altered the course of the project. Inviting the younger Florentine—who got involved only after Ghiberti, Caglioti says—led to many of the font's most revolutionary elements, especially the freestanding bronze putti that decorate the tabernacle, which are among the first and most influential examples of dynamism in Renaissance sculpture.

The font “began without Donatello,” Caglioti says, “but then it became a work by Donatello.”