In the opening pages of Leonardo da Vinci: An Untraceable Life, Stephen J. Campbell, the Henry and Elizabeth Wiesenfeld professor of art history at Johns Hopkins University, observes that around 250 new books were released to coincide with the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death (1519), adding to an already vast corpus of publications. In this crowded field, Campbell frames his fascinating new study as an “anti-biography”, which attempts to unpick, over five main chapters, the mythology surrounding his subject and to reassess what we really know about Leonardo beyond some of the basic facts: his birth in Anchiano, Tuscany, in 1452 as the illegitimate son of the notary Ser Piero da Vinci; his apprenticeship in Andrea del Verrocchio’s workshop; his movements between Florence and Milan; his relocation to the French court of King Francis I and death in Amboise.

Gaps have been filled with speculative theories that appeal to modern audiences

Around 7,000 sheets of Leonardo’s notes have survived, covering myriad subjects from optics, anatomy, engineering and hydrodynamics to discussions on Aristotelian philosophy, and artistic theory and practice (the latter collated and published posthumously in 1651 as his Treatise on Painting). Campbell argues that Leonardo reveals little about himself in these copious writings and, unlike some of his contemporaries, such as Michelangelo, who left quantities of private correspondence, we have less than a dozen of Leonardo’s personal letters to give any further insight. Campbell suggests that the fragmentary nature of the archival record has encouraged the gaps to be filled with speculative, sometimes outlandish theories that appeal to modern audiences, and psychological projections that align with modern sensibilities. The consequence, he concludes, has been the creation of semi-fictive “Da Vinci Worlds”, which promote the myth of a solitary genius, ahead of his time, thwarted and misunderstood by the lesser minds around him. In popular culture, Campbell contends, Leonardo has become a relatable figure, “something between a celebrity brand and an inspirational role model” akin to a present-day tech entrepreneur. The book is intended to correct this anachronistic view by re-situating Leonardo within the European artistic and intellectual milieux of the late 15th and early 16th centuries, providing a broader context for his creative output while grounding him in the world in which he lived.

Media manipulation

Working from this fundamental premise, the first three chapters chart the construction of the Leonardo myth, starting in chapter one with a dissection of the Da Vinci World experience and the ways in which Leonardo’s legacy is presented to the public. Here, Campbell explores how his subject’s cult status has been manipulated by the media, the art market and the commercialisation of cultural artefacts, and laments that rigorous academic scholarship is increasingly sidelined in favour of headline-grabbing sensationalism. In chapter two, Campbell reassesses the “debatable facts” about Leonardo, taken from the artist’s own writings and contemporary accounts of his life, and criticises the practice of “archival cherry-picking” to bolster ahistorical theories about Leonardo’s interior life, particularly in relation to his sexual identity, spiritual beliefs and “sense of self”. Chapter three examines the emergence of historical biography writing in the 19th century, when the term “Renaissance” was first coined and denoted as the precursor to modernity. Taking in a wide range of published material up to the present day, Campbell discusses how Leonardo has been fitted into this literary tradition to suit the varying agendas of modern authors such as Sigmund Freud, whose psychoanalytical study of Leonardo’s life was first published in 1910.

Studio fetishisation

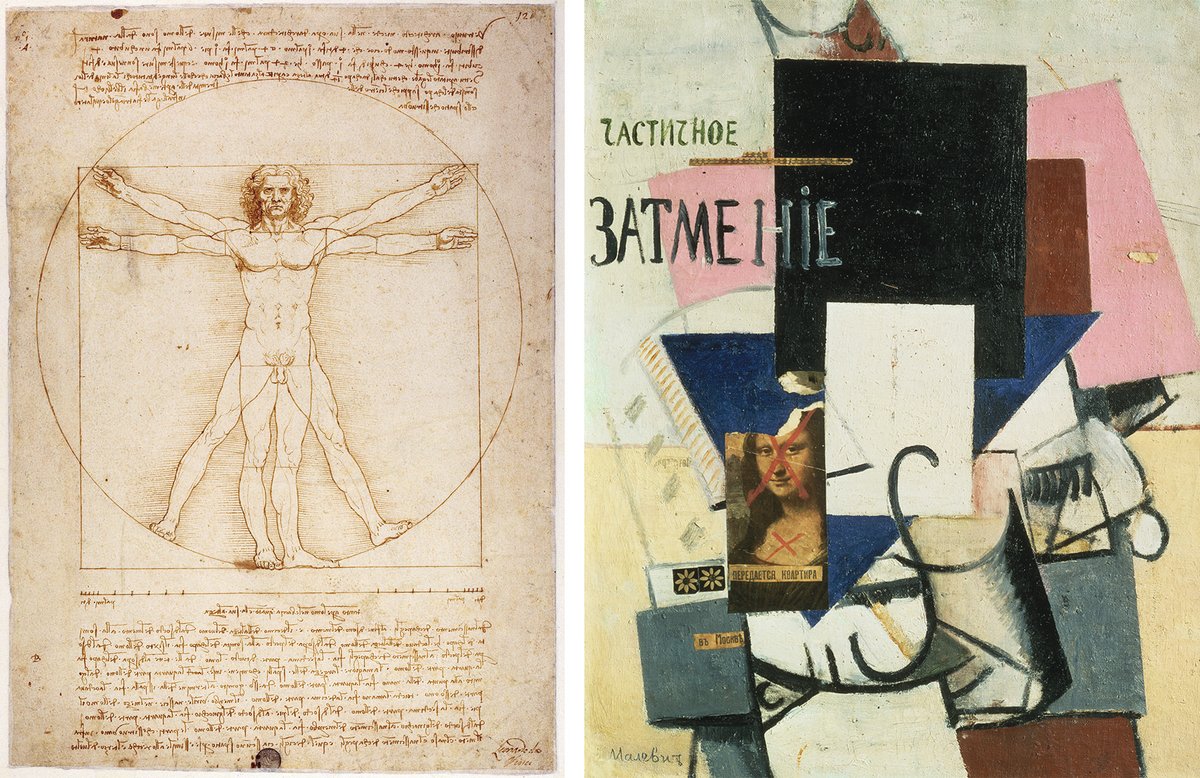

In chapters four and five, Campbell moves on to present his antidote to the Da Vinci World phenomenon, firstly by looking at the evidence of Leonardo’s engagement with contemporary philosophical debates on artistic theory and practice. Campbell conducts a detailed analysis of the intellectual ideas circulating during Leonardo’s lifetime, focusing on the writings and publications of Leon Battista Alberti and other artists, who were systemising the principles of their craft to better demonstrate the application of the theoretical knowledge advocated by humanist scholars within their art. Finally, chapter five considers Leonardo’s workshop as a busy, collaborative space, to argue against the notion of his solitary genius. Campbell evaluates the ideas and techniques Leonardo transmitted to his followers, the so-called “Leonardeschi”, whose surviving work continues to contribute to the fetishisation of anything that Leonardo himself might have touched.

Campbell’s study covers a broad terrain, and he deftly explains some of the methodological approaches in art-historical writing and complex Renaissance theoretical concepts for a non-specialist reader. The book also includes some important reflections on the factors that influence how art and culture are consumed in modern society and the ever-growing pressures on cultural institutions to reach wider audiences. Throughout, Campbell acknowledges the essential unknowability of past lives and the importance of establishing historical context. By drawing on a wealth of sources, both contemporary and modern, he explores Leonardo’s mental landscape and working practice to achieve his aim of presenting the artist-polymath as a man of his time, with “a life entangled in other lives, shaped by the clamour of the workshop, as well as the performative poise of the court, of random encounters and serendipitous connections”.

• Stephen J. Campbell, Leonardo da Vinci: An Untraceable Life, Princeton University Press, 352pp, 47 colour & 344 b/w illustrations., $37/£30 (hb), published 4 February/1 April

• Sarah McBryde is an independent scholar and series assistant editor for Elements in the Renaissance (Cambridge University Press)