Iain Pears calls his book “a simple tale of two people from a world long ago who meet and fall in love”. But the story of how Larissa Salmina (1931-2024) and Francis Haskell (1928-2000) found each other in 1962, at a random restaurant in Venice, is anything but simple. A bestselling author of detective novels, Pears weaves his disparate sources—Salmina’s own recollections, shared with him shortly before her death, and the copious diaries kept by Haskell—into a virtually seamless whole: a moving elegy for a bygone Europe, where art still mattered and borders were there to be crossed.

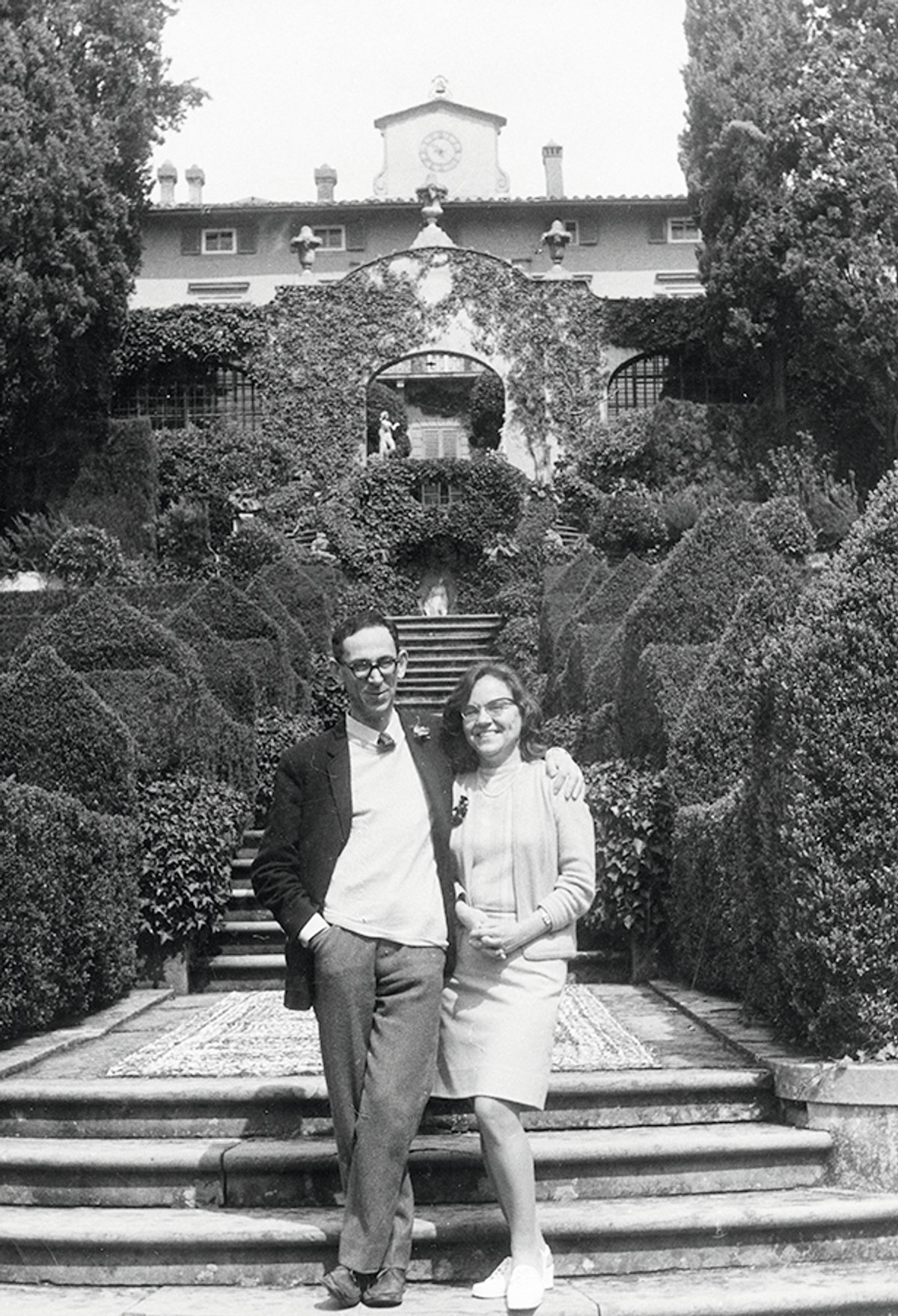

When they met, Salmina was the curator of drawings at the Hermitage Museum in what was then Leningrad and Haskell was the librarian of the fine arts faculty at Cambridge University. (Rail-thin and bespectacled, he looked the part, too.) But in other ways, their lives, despite the book’s title, were not really parallel.

Salmina was tough, creative and willing to flout the law. As a teenager she lived through the siege of Leningrad (1941-44), wandering along streets covered with corpses, past houses set on fire by German bombs. By contrast, the austerity Haskell endured was one familiar to many British boys stuck in private boarding school: bad food, fickle plumbing and no heat. Dispatched to Eton by indifferent parents, Haskell suffered, Pears observes, the expected consequences: inhibitions galore, nagging insecurity about his sexuality and a lifelong hankering for emotional warmth.

Salmina’s parents did not lack warmth but struggled merely to stay alive. Her father, Nikolai Salmin, an officer in the Soviet army, might have escaped Stalin’s purges only because someone else with the same name did not. And her charismatic mother, Vera, who knew how to, in Pears’s phrase, “short-circuit the system”, imparted that talent to her daughter. Soon, Salmina was forging signatures and opera tickets; in Salmina’s Russia, people got by thanks to coincidence and craftiness.

Salmina never completed her doctoral thesis on the 18th-century Venetian painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo but, nonetheless, she was appointed the Hermitage’s curator of drawings at the age of 26. “The Soviet regime,” notes Pears, who excels at injecting small doses of sarcasm into his crystal-clear prose, “mixed an unpredictable understanding of the importance of expertise with the periodic purges and persecution.” Yet when Salmina was chosen to represent the Soviet Union at the Venice Biennale in 1962, this was not because of her art-historical knowledge. Rather, an elderly colleague had died while abroad, causing the government considerable expense. “She looks healthy,” the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev declared when he saw Salmina’s profile. “Send her.”

Haskell had begun his quest for self-liberation in 1952, when he moved to Italy to identify the “Jesuit style” in art. (There was none, he decided.) Instead, he immersed himself in a twilight world full of weird and exciting characters: the old women muttering prayers in dark chapels, men reporting to brothels as if for medical check-ups, the animated old puppeteer in Sicily who seemed to have stepped out of a Charles Dickens novel.

As Haskell’s relationship with Salmina blossomed, his diary-keeping stopped

The night after their fateful meeting in Venice, a sleepless Haskell turned up at Salmina’s hotel room to ask for help with his earplugs. And thus a relationship began that, as Pears describes it, “swept both of them along almost against their will”. Haskell shed his remaining neuroses like a crab its shell: “A new and thrilling experience,” he exulted in his diary. As Haskell’s relationship with Salmina blossomed, his diary-keeping stopped. “He had,” comments Pears, “a far better companion to talk to.”

The couple were married in Leningrad’s Palace of Marriages on 10 August 1965. In England, Salmina reinvented herself as a specialist in Russian art, while Haskell became professor of the history of art at Oxford University. He retired in 1995, the author of celebrated works such as Rediscoveries in Art (1976) and Taste and the Antique. Pears, one of his students at Oxford, rarely mentions Haskell’s scholarship, treating his former tutor’s marriage as his proudest accomplishment. Yet I believe that Haskell’s delight in Salmina’s company filtered into his writing, too. Take his “In Love with Light”, a late essay in which, now close to 70 years of age, Haskell rejected claims that Tiepolo, his wife’s favourite artist, was superficial and pompous. Just look at Tiepolo’s paintings, he insisted, and you will find there “a sense of love and yearning” that rings “absolutely true”.

• Iain Pears, Parallel Lives: A Love Story from a Lost Continent, William Collins, 288pp, 40 illustrations, £18.99 (hb), published 8 May

• Christoph Irmscher is a critic and biographer