Provocative, punky and perverse are just a handful of the adjectives often used to describe the work of Helen Chadwick (1953-96). Yet they only hint at the depth of the British artist’s vision. Chadwick was an artist of rare material and emotional literacy and her influence on the language of contemporary British art remains palpable.

Chadwick was widely exhibited during her lifetime, but attention to her work declined following her unexpected death in 1996. It is only in recent years that the significance of her corpus has been acknowledged afresh. Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures is, rather surprisingly, the first critical biography of the artist. It includes contributions from the historian Marina Warner, the curator Katrin Bucher Trantow and the artist Maria Christoforidou, among others. The publication is edited by Laura Smith, the director of collection and exhibitions at the Hepworth Wakefield, where a touring exhibition of the artist opens this month (17 May-27 October).

“I’d argue that both the book and exhibition should have happened sooner,” Smith says. “British art wouldn’t look the same now without her.” It is fair to say that the emergence and output of a certain group of Young British Artists (YBAs) might have unfolded quite differently without Chadwick. Many of the most daring YBA voices—Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas and Anya Gallaccio—were deeply influenced by her focus on the body and her own biography.

Seduction and disgust

At times Chadwick’s reputation as a perpetual experimentalist and devoted agent of reinvention has left her somewhat siloed. She is not easily put in a box. As a student in the 1970s, she had little interest in traditional mediums like drawing or painting, arriving at the conclusion that they were still predominantly the domain of male artists. Instead, she turned to installation, photography, sculpture and performance—mediums not yet fully realised in institutional contexts and brimming with untapped potential. In Untitled (Eat Art) (1973), for example, she cast her own face in jelly and invited viewers to consume it, establishing a career-long fascination with the slippage between seduction and disgust.

However, where once Chadwick was considered an unacceptable face of feminism, in the decade immediately following her death, the use of her own body had not only lost its power to provoke, it had been co-opted, diluted and folded seamlessly into the fabric of mainstream visual culture. Still, there is a case to be made for Chadwick’s relevance today. In a conversation with Smith included in the monograph, The Art Newspaper’s contemporary art correspondent Louisa Buck declares that the artist’s work remains current precisely “because it is really about who and what we are: physically, intellectually and materially. Whatever form it takes.” She adds: “At its core, Helen’s work is an exploration of selfhood and identity before identity politics became widely foregrounded.”

Domestic subversion

Across the full sweep of Chadwick’s career—from her MA degree show In the Kitchen (1977), where she subverted domestic appliances with conceptual and comic inventiveness, to her Piss Flowers (1991-92), made by taking a cast of snow she had urinated on—runs a fascination with some of life’s most pressing themes; desire, gender, sex, beauty, biological need, disease and decay.

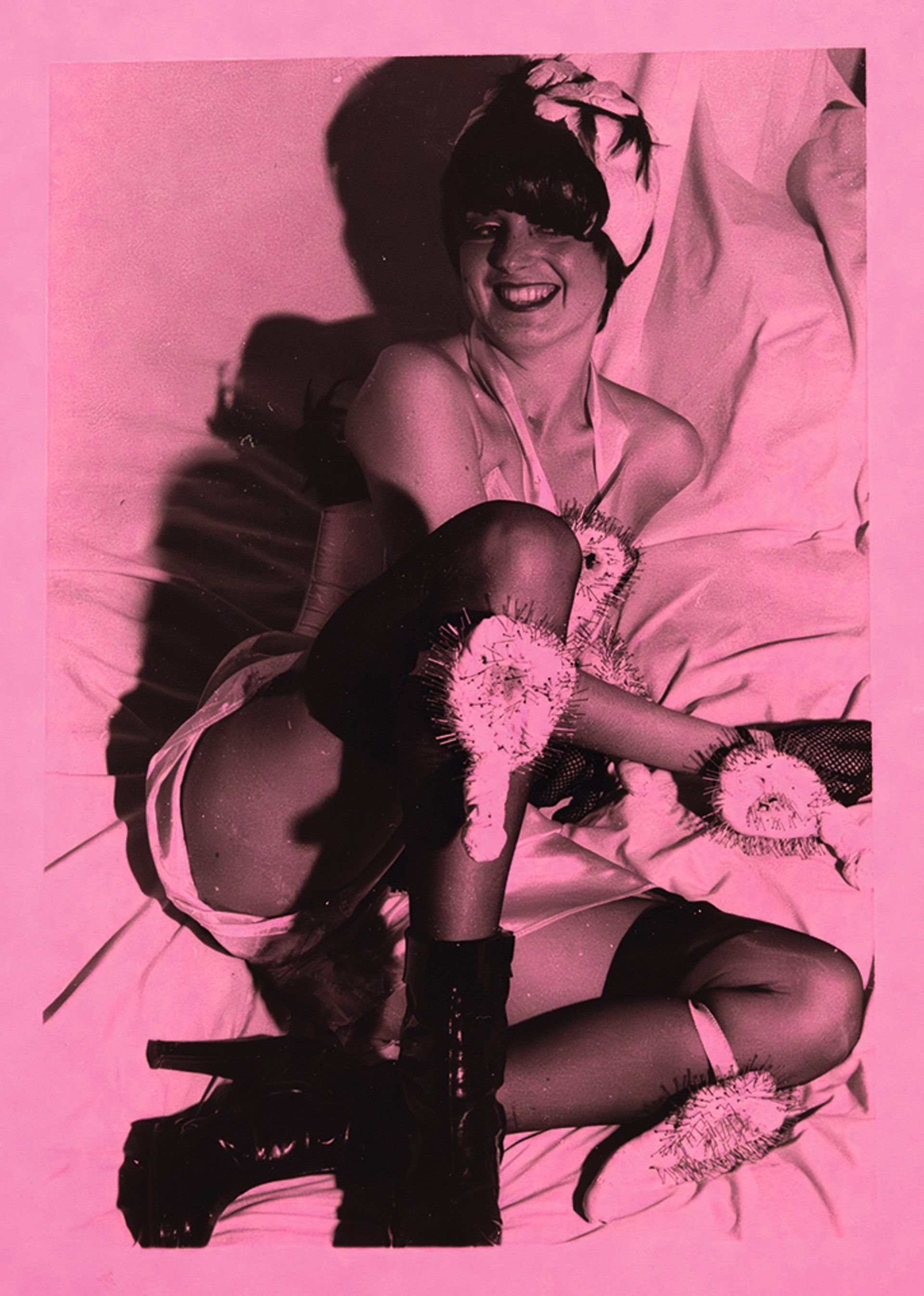

Chadwick in fancy dress

© Estate of Helen Chadwick, Anya Fiáine-Fox

Readers are also reminded of the widely reported incident during Chadwick’s 1986 solo exhibition Of Mutability at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, where her sculpture Carcass, a 2m-tall glass tower filled with rotting vegetable matter, leaked and eventually collapsed, spewing ten gallons of fermented liquid across the galleries.

“She employed such a diverse and surprising range of materials as an attempt to make us respond physically to her work,” Smith says. Raw meat, flowers, bodily fluids and chocolate are also counted among her subject matter. “Chadwick’s thinking,” Smith says, “was that, if our reactions are bodily, almost like reflex actions, then our responses to her works might be more genuine and subjective—unaffected by societal or cultural constructs.”

Perhaps most enlightening amid the breadth of work contained in the Chadwick monograph is proof of her exacting production values. “The first time I visited her archive at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds, I think I was expecting something a bit more punky, but it is immaculate,” Smith says. “Her handwriting is tiny and oh-so neat, her hand stitching pin-perfect and her bookbinding skills are incredible.” This blend of precision and rebellion, of rigour and subversion, is what sets Chadwick apart—it is art that never settles, that prods and riles and roars until you cannot ignore it any longer.

“I really believe that the body of work that Helen left us with is one of the most accomplished of recent generations,” Smith says. “I only wish that she had lived longer to be able to keep making and inspiring us.”

• Laura Smith (ed), Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures, Thames & Hudson, 272pp, £30 (hb)

• Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures, Hepworth Wakefield, 17 May-27 October