Researchers at the Chavín de Huántar archaeological site, located in the central Peruvian Andes, have revealed an ancestral practice that sheds new light on the power dynamic and worldview of the Chavín, a major pre-Incan culture.

John Rick of California’s Stanford University and Daniel Contreras of the University of Florida led the exhaustive study, which has shown that the Chavín used psychoactive plants as an integral part of their ceremonial rituals more than 2,500 years ago.

An interdisciplinary team of experts from Peru, Argentina, Chile and the US focused on analysing small tubes carved from bird bones found at the heart of Chavín’s imposing stone structures. Chemical and botanical testing on the tubes revealed the presence of nicotine from wild relatives of tobacco, as well as vilca bean (Anadenanthera colubrina), a plant containing dimethyltryptamine (DMT)—a potent hallucinogen also found in ayahuasca.

Tubes carved from bird bones and used to inhale tobacco and hallucinogenic vilca Courtesy Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

“The tubes are analogous to the rolled-up bills that high-rollers snort cocaine through in the movies,” Contreras told Live Science.

Contreras, co-author of the scientific paper detailing the findings—published on 5 May in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences—explains that these rituals were part of a strictly regulated practice, probably reserved for the elite, who met in secret rooms inside the monumental complex.

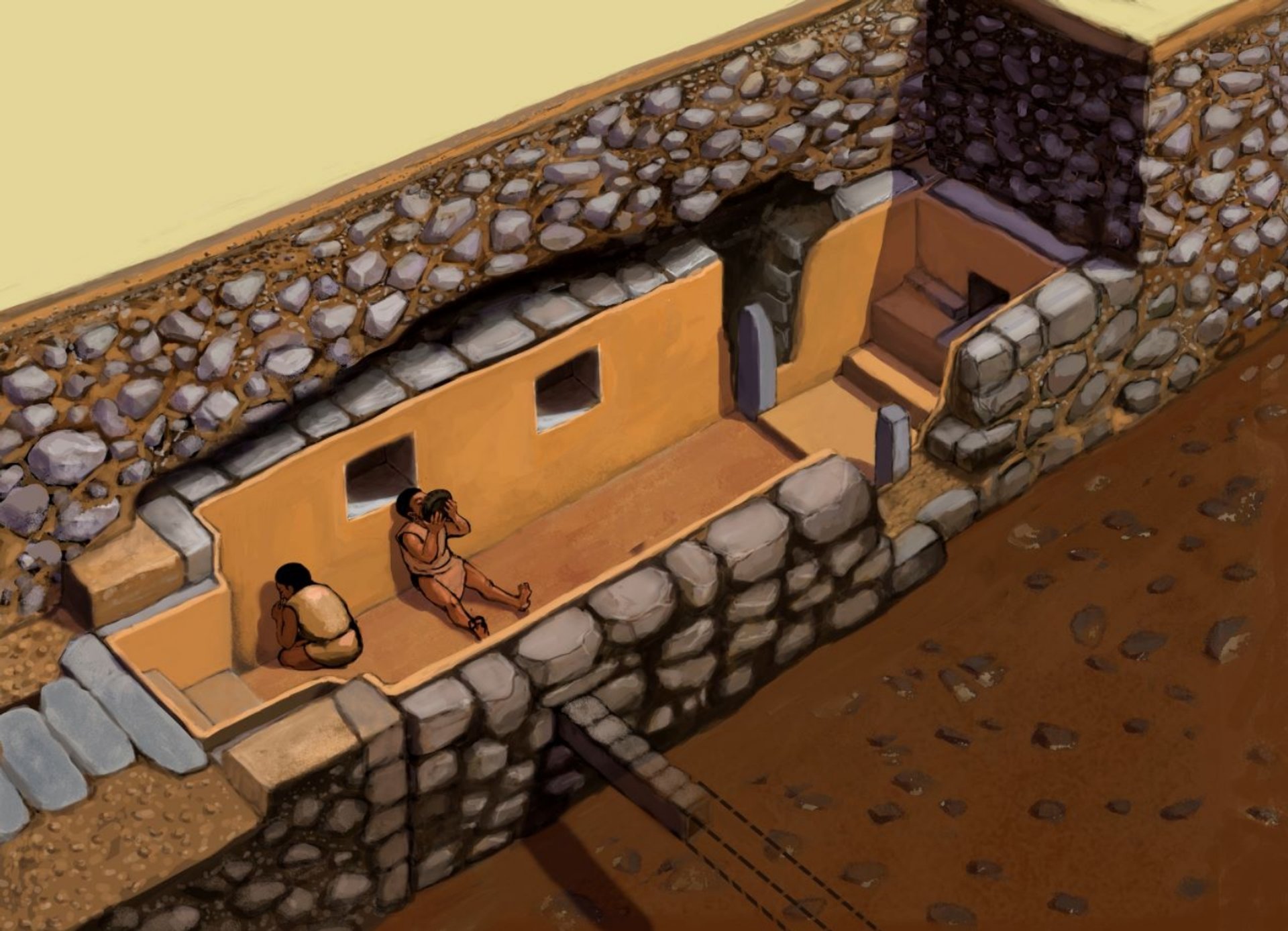

Chavín de Huántar flourished as a major centre of ritual activity between 1200BC and 400BC, well before the rise of the Inca Empire (AD1400 to AD1533). The architectural complex includes imposing stone structures arranged around open squares. As the centuries passed, the buildings’ expansion led to the creation of labyrinthine interior spaces known as galleries. The gallery where the psychoactive paraphernalia was found was sealed around 500BC and remained intact until it was excavated in 2017. It is here that researchers discovered 23 artefacts carved from animal bones and seashells, including tubes and spoons that were apparently used to inhale substances. Experts suggest that these experiences induced by psychoactive plants must have been profound and even overwhelming for those who participated in them.

Reproduction of the secret room where the elite inhaled hallucinogenic substances Courtesy Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Archaeologists have discovered trumpets made of seashells (known as pututus) and acoustic chambers designed to amplify impressive musical performances. Contreras, who has spent nearly three decades studying Chavín de Huántar under Rick’s supervision, argues that these ceremonies were fundamental in shaping the earliest class structures in the Andean region. Unlike other societies, which imposed their will through war and coercion, the Chavín likely consolidated power via persuasion, induced by immersive rituals that convinced the population of the grandeur of the collective project.

The exclusive nature of the Chavín’s rituals stands in marked contrast with the community use of hallucinogens documented in other ancient cultures. Archaeologists discovered the tubes, which date from 2,500 years ago, in private chambers that could hold only a small number of people. This secrecy and control likely enhanced the aura of mysticism and power surrounding the ruling elite.

These findings are a significant contribution towards answering centuries-old mysteries surrounding Chavín de Huántar, which was declared a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1985 and is located at an altitude of more than 3,000 m above sea level. Ever since its earliest excavations, begun more than a century ago, there have been debates regarding its relationship to previous societies, which were considered more egalitarian, and the mountain empires governed by powerful elites that subsequently arose. A controlled access to mystical experiences offers a plausible explanation for this major social transition, a fact that has only been discovered thanks to decades of painstaking archaeological work and the use of cutting-edge testing methods.