Rumours of painting’s demise have been greatly exaggerated, as Mark Twain might have said. The most expensive work ever? A painting (Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi, $450m). The most expensive work by a living male artist? A painting (Jasper Johns’s Flag, $110m). The most expensive work by a living female artist? A painting (Marlene Dumas’s Miss January, $13.6m). And on and on.

As a survey of the painter Jenny Saville opens at the National Portrait Gallery in London this month (20 June-7 September)—just one of a vast number of recent painting exhibitions, gallery shows and auctions—the medium continues to be the art market’s primary driving force, and by far the most popular choice for artists and art students around the world. How has painting not only endured, but thrived? And is 2025 peak painting, or can the form continue to reach new heights?

Unrivalled commercial potential

Of the four artists shortlisted for the 2025 Turner Prize, the multidisciplinary practitioner Rene Matić might be the critics’ favourite. But the nominee with the highest international profile by far is the UK-based Iraqi painter Mohammed Sami.

On 16 May, his work Poor Folk II (2019) sold at Sotheby’s for $571,500, surpassing its presale high estimate of $500,000. This follows the first work in that series, Poor Folk I, which had a presale estimate of £60,000-£80,000, selling for £558,500 ($686,600) in October 2023—roughly half a million pounds more than was expected. Not too bad for an artist whose works first sold at Patrick Heide Contemporary Art in London for around £15,000.

“Sami explores the potential and limitations of contemporary painting to negotiate the memories of moments past,” Priyesh Mistry, the associate curator of Modern and contemporary projects at the National Gallery in London said at the Turner Prize shortlist press conference. “We were struck as a jury by the ability of Sami’s complex and highly-skilled paintings to contest the assumed power held and endorsed by [the] history of art.”

Painting and its ability to speak to the moment is the focus for numerous curators on the 2025 international exhibition circuit. Two shows—Painting after Painting at the Municipal Museum for Contemporary Art in Ghent (SMAK, until 2 November), and the recently closed R U Still Painting???, curated by the Falcon Art Collective in a corporate, under-construction space in Midtown New York—present surveys of how artists are using the medium in Belgium and the US, respectively. Both titles reference the many declarations of the demise of painting, ever since the melodramatic French painter Hippolyte-Paul Delaroche first saw a daguerreotype in the early 19th century and declared painting dead “from now on”.

“The art of painting has become not so much difficult as impossible,” Kenneth Clark wrote in 1935, before proceeding to write a “survey of the field”, as he put it, to show what made it so.

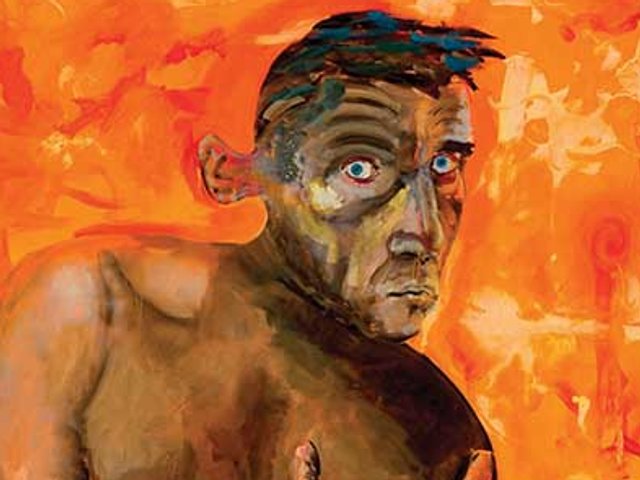

When Marlene Dumas’s Miss January (1997) sold for $13.6m last month, it became the most expensive work by a living woman artist Sipa US/Alamy Stock Photo

And yet, at every turn, artists, critics and art historians have gone on to prove the medium extant—vibrant, even. “Apparently it’s very difficult to kill painting,” says SMAK’s artistic director, Philippe Van Cauteren. “Every 20, 25 years, there have been various attempts to get rid of painting with different kinds of motives or reasons. But there is in the medium, apparently, a strength or a tendency for survival.” Among the artists he has included in Painting after Painting is Vincent Geyskens, who has long described both his work and the practice at large as a “zombie”—painting as the undead medium.

The operative question, though, is whether it ever really went away at all. When asked whether the declaimed end of painting has ever been evident in the art market, whether the medium ever lost its economic clout, Lucius Elliott, the head of Sotheby’s contemporary art marquee sales in New York, answers with an allusion. Francis Fukuyama declared the end of history, Elliott says, because neoliberalism is the hegemonic idea. So too in art: painting is the medium that cannot be surpassed. Put another way, as Umer Butt, an artist and founder of Grey Noise gallery in Dubai says, “Painting is the king.”

The numbers bear that out. That same October 2023 auction that saw Sami hit his all-time auction high, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s Six Birds in the Bush (2015) sold for £3m ($3.6m), a whopping £1.2m over its high estimate. This led to Yiadom-Boakye’s ranking as the third-most bankable artist born after 1974 in Artnet’s 2024 Intelligence Report Mid-Year Review.

Most of Butt’s counterparts in Dubai show painting, the consensus among dealers being that you would be daft not to. As he puts it, “It’s easy—easy to transport, easy to hang in a collector’s house.” So too in the Chinese art market. The painter Chen Ke, whose solo exhibition Bauhaus Unknown is on at UCCA Beijing (until 7 September), says painting holds a dominant position in the country. If the most prosperous era for traditional Chinese ink painting has passed, “contemporary Chinese painting, on the other hand, does not seem to have such a serious problem”.

Despite loving the medium, Butt mostly does not show it; he only has two painters on his conceptually-steeped roster. There are others he would love to show, but he is unable to afford to ship their works because blue-chip gallery interest has made their insurance value skyrocket. It is partly this unrivalled commercial potential of painting that makes his relationship to the medium, to use his term, “conflictual”.

The word ‘painting’ is as strong and as complex and as ambiguous and difficult as the word ‘museum’Philippe Van Cauteren, artistic director, SMAK

“The word ‘painting’ is as strong and as complex and as ambiguous and difficult as the word ‘museum’ itself,” Van Cauteren says. “Maybe the only way to erase that memory or that reading is to put another layer on top of it.” Perhaps, he says, the only way to open up new possibilities for painting is, simply, to paint: to “over-paint painting”.

Overturning historical narratives

The art historian Sofia Gotti, who lectures in curating at the Courtauld Institute in London, points to the heavy presence of painting at the 2024 Venice Biennale, which she co-curated, to highlight the international commonalities in how artists are in fact “over-painting painting”. It was not that the artistic director Adriano Pedrosa’s team set out to spotlight contemporary painting from across the world. Rather, many of the artists his team invited to take part in Stranieri Ovunque—Foreigners Everywhere continue to find the medium a useful tool for centring Indigenous or so-called outsider perspectives and dissecting Eurocentric colonial narratives.

How the history of art, and of painting especially, has been written has of course been key to precisely those exclusionary narratives. But artists are no longer necessarily finding a denial of the medium to be helpful in countering them. Some want to tell stories. Others want earnestness. Some want romance. Many, Van Cauteren notes, are yearning for skill.

Thriving discourse

In 2023, the year before he died, Frank Auerbach described how he came to paint and draw in the 1940s and 50s, at the tail end of Modernism. “I was taught by all sorts of intelligent people, who I was very pleased to be in contact with,” he said. “One of the great things at London art schools is that we were continually offered a great number of alternatives. We tried almost everything, or thought about everything, that was on offer, until we found something that was difficult enough and puzzling enough and intriguing enough to sustain us for a lifetime.”

In January 2025 the British painter Jake Grewal, by contrast, spoke about his first forays into figurative painting at art school in the mid 2010s as a confrontation. “There was this kind of real idea that you had to be academic in the way you approach painting,” he said. “It was also quite satirical, ‘Oh, I’m making a bad painting because I’m making fun of painting’.”

Onya McCausland, the head of undergraduate painting at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, believes painting endures as a medium precisely because of the thriving discourse it engenders: its capacity to be self-reflexive. She sees this periodic existential questioning not as justifying the medium’s existence, but rather as its “lifeblood”.

This metaphor resonates particularly with McCausland, because it is precisely the physicality of painting—the way it works beyond the verbal or the conceptual—that gets students excited about engaging with it in the first place. “They love its capacity to be flexible and versatile, and very connected to the body,” she says. “It’s so close and fleshy and physical and drippy and liquid and unwieldy and leaky. The medium itself is close to hand.”

The Senegal-born, Brussels-based painter Libasse Ka, who is showing in the SMAK exhibition, described his allegiance to his craft in November 2024. “I know that as long as I paint, I live. I’ve painted when I’ve been very broke. I’m painting now. No one will take it from me. That’s my treasure.” Chen Ke, meanwhile, describes painting as going “directly from the heart to the hand, with few barriers in between”.

Whether the upcoming generation of collectors will turn their backs on analogue 20th-century art or not, the potential of painting—embodied, slippery, direct, tangible, conflictual—will see it endure, regardless.