Between 1968 and 1972, while men walked the surface of the moon and hippies dropped acid, a young man in his mid-twenties was photographing an entirely different world: the dire living conditions of the urban poor in England and Scotland, where little had changed since the Victorian era. The photographs Nick Hedges made during this time were used in a national housing campaign that would have a profound effect on the British public and help to make the case for a change in the law. This change eventually arrived with The Housing (Homeless Persons) Act of 1977, which was a major step forward in legal protections for homeless people.

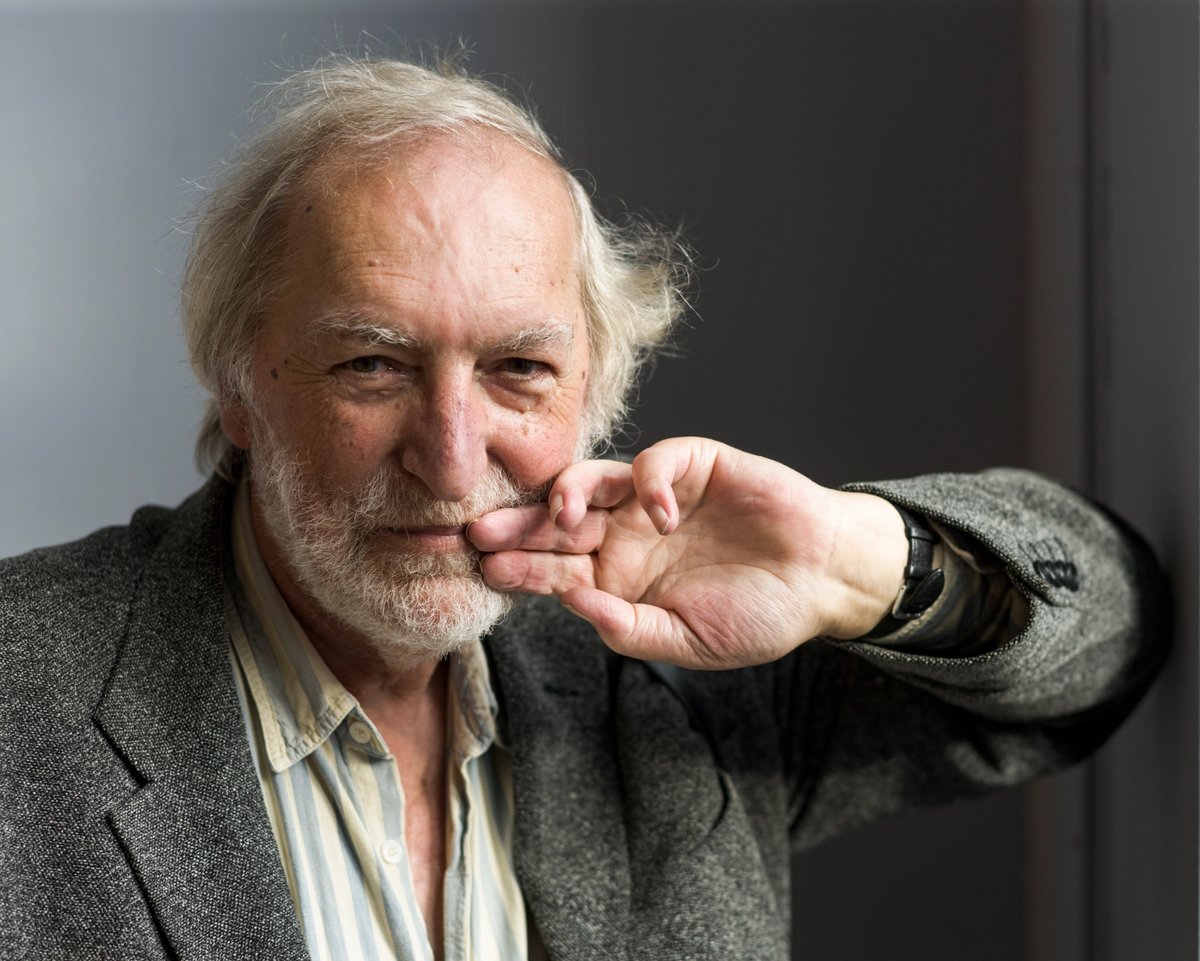

For Hedges, who died on 8 June, aged 81, this work cemented his conviction that photography could be a powerful tool for social change. The pictures were shown in a travelling exhibition organised by the Victoria & Albert Museum in 1974, but were not seen again in public for another 40 years. After this the photographer received some belated recognition, but none of his later works eclipsed the images of slum housing that marked an early highpoint in his career.

Hedges was born in Bromsgrove in the West Midlands in 1943. Aged 24, while studying photography at Birmingham College of Art, he began a project capturing the circumstances of people living in the city’s most dilapidated housing stock, built cheaply to accommodate the rapid population growth that came with the industrial revolution a century earlier.

He was shocked by the material poverty he saw, but also by the sense of hopelessness of the families. Many lived in slum conditions that had been condemned before he was even born, yet had been left in extreme deprivation while authorities nationwide figured out how to tackle the problem of up to three million people who needed urgent rehousing.

New tower blocks Hockley, 1968

Nick Hedges

Photography as activism

The photographs from this final-year art school project were seen by Des Wilson, the director of Shelter, then a new charity campaigning for an urgent response to the crisis. Hedges was employed by Shelter straight from college as a researcher and photographer. He was tasked with travelling England and Scotland to capture the human consequences of slum housing for the charity’s Face the Facts campaign, which urged the government to change its definition of homeless to include those living in property deemed “unfit for human habitation”.

Hedges knocked on doors and met and recorded people in Birmingham, Bradford, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool, London, Newcastle, Salford and Sheffield. Men, however, rarely appeared in the campaign. Hedges said that they often felt too ashamed to be photographed, but he also observed that Shelter gravitated towards pictures of women and children, which were seen as more sympathetic.

After leaving Shelter in 1972, Hedges spent the rest of the decade as a freelance documentary photographer, working for Disability Income Group, Mencap, Population Countdown, the BBC, Penguin books and New Society magazine. He was one of three photographers commissioned to make an exhibition titled Problem in the City by the Royal Town Planning Institute which was shown at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, in 1976. The show, with its call for greater consultation and participation by the community in the planning process, apparently did not go down well at the institute’s annual conference.

Alongside working as a freelance photographer, Hedges also shot independent projects, gravitating towards organisations such as Half Moon Gallery in London, Side Gallery in Newcastle and Camerawork and Ten.8 magazines, which, like him, saw photography as a form of activism. In 1976 he was awarded an Arts Council Fellowship to photograph workers in factories and steelworks in the West Midlands, spending two years on the project.

The results were exhibited at Half Moon, and by the British Council in Paris. A book, Born to Work, was published three years later. In 1979, he was commissioned by Side Gallery to document the fishing industry in North Shields, and throughout the second half of the 1970s he continued his project, I’m a Believer, photographing the rites and rituals of the many different religions practised in Wolverhampton.

From 1980 Hedges taught at West Midlands College, becoming subject leader in photography at the University of Wolverhampton in 1988, and retiring in 2003. In 1981 the photographer donated his remaining collection of his Shelter negatives, contact sheets, and prints to Library of Birmingham.

Humanity and scale

Two decades earlier he had given 1000 prints to the then newly opened National Museum of Photography, Film & Television in Bradford, which is now the National Science and Media Museum. Hedges, presumably wanting to protect the subjects of the images, which included many children, from the stigma of poverty, put an embargo on the images being seen by the public.

However, the archive was seen by Hedy van Erp, an independent curator from the Netherlands, who was invited to put together an exhibition at the Media Space gallery at the Science Museum, London, in 2014, by which time the embargo had been lifted. The show was titled Make Life Worth Living.

Nick Hedges

“Although these photographs have become historical documents, they serve to remind us that secure and adequate housing is the basis of a civilised urban society,” Hedges said at the time. “The failure of successive governments to provide for it is a sad mark of society’s inaction. The photographs should allow us to celebrate progress, yet all they can do is haunt us with a sense of failure.”

The exhibition brought an almost forgotten aspect of recent history back to the fore, and brought newfound recognition to the photographer. Van Erp tells The Art Newspaper that she was shocked to see such images from western Europe made during the last quarter of the 20th century, recalling that she “had to put them away after a couple of hours with them, because they were just too heavy”. However, the curator also says that the humanity and scale of the work sometimes took her breath away. For her, the difference between Hedges and some of his better known contemporaries is that, “he spoke extensively with all the people he photographed. He got to know them".

The concerned documentary photographer

In 2015, Hedges contributed to a spin-off documentary, Slum Britain: 50 Years On made by Channel 5, comparing the conditions of 1968 with the modern-day housing crisis. The same year, his photographs were shown in a group exhibition titled, Not Yet. On the Reinvention of Documentary and the Critique of Modernism, staged by the Museo Reina Sofia, which acquired a substantial collection of vintage prints of his work.

In 2021, Bluecoat Press published Hedges' work for Shelter in a book titled Home, alongside another titled Street. And now his student work has been brought together with the Shelter photographs for an exhibition at Birmingham Back to Backs, a National Trust property that preserves some of the last remaining housing that Hedges photographed more than half a century ago. Home in the Shadows runs until the end of September.

Paul Hill, a contemporary of Hedges and an influential photographer and teacher who was in part responsible for him getting the 1976 Arts Council Fellowship, says the image maker epitomised the concerned documentary photographer. “He was concerned not only about injustice in society, but in the world of work,” Hill explains.

“He showed a juxtaposition of things in the factory workplace—posters on a wall, birthday cards strung up. You got a feeling that these were real spaces…The pictures transcended the information that was captured by the camera. And that juxtaposition, that ambiguity, is a powerful way to tell a story with photography.”

Rupert Nicholas Wilmore (Nick) Hedges; born Bromsgrove, Worcestershire 31 December 1943; married Diana Roberts (two daughters; marriage dissolved); died 8 June 2025.