Over the past half-century, Martin Parr (born Epsom, Surrey in 1952) has gained a reputation as one of Britain’s foremost documentary photographers, publishing more than 100 photobooks and taking part in countless exhibitions. In 2017, the Martin Parr Foundation opened in his hometown of Bristol, housing his extensive archive and offering a dedicated space to celebrate the best of British and Irish photography. In an era marked by oversaturation, Parr’s vivid photographs—affectionately skewering mass tourism and consumer culture—have become instantly recognisable, known for their wry humour and knack for noticing the oddness of the here-and-now.

Despite his obvious legacy, Parr’s career shows no signs of slowing down. On the contrary, following a cancer diagnosis in 2021, there is a sense of urgency to his activity. Parr’s photographs of Bristol Pride parades are currently on display in Bristol Museum and Art Gallery (until 29 March 2026), while 2024 saw the release of Lee Shulman’s warm-hearted documentary, I Am Martin Parr, which follows the photographer to several UK sites that feature in his photographs.

Badge of honour

Parr’s latest publication, written in collaboration with the author and biographer Wendy Jones, takes the shape of an informal autobiography, generously illustrated with pictures spanning his career. The title, Utterly Lazy and Inattentive: Martin Parr in Words and Pictures, comes from a comment in a school report, a phrase Parr now wears as a badge of honour. In fact, far from idle, the young Parr was an avid birdwatcher, trainspotter and enthusiastic collector: the latter trait has endured well into his seventies. Where youthful snapshots show him with a shelf of bird pellets and fossils, he is now known for his huge library of photobooks and Russian space-dog memorabilia.

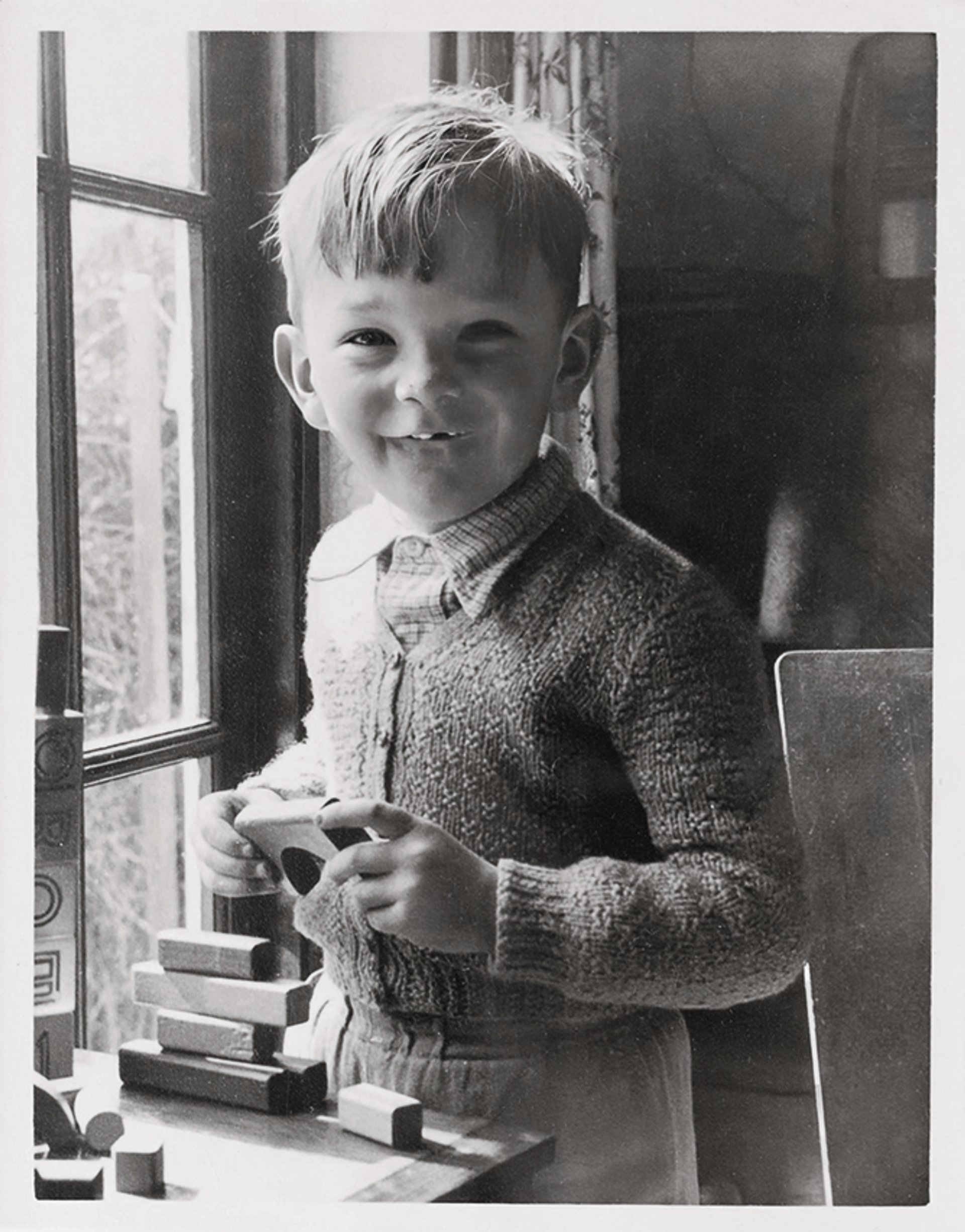

Martin Parr, aged five, photographed by George Parr, his grandfather, in 1958 © Martin Parr/Magnum Photos

The book’s opening picture shows a young Parr holding a bridge-shaped wooden building block. One would be excused for thinking he is clutching a small camera. More pictures from the Parr family albums follow, establishing the publication’s casual, even chatty tone, as though we are leafing through the book with Parr beside us, offering explanations as to who or what we are looking at. (“Oh, there’s Granny,” begins one recollection.) As such, there is an intimacy to Parr’s storytelling, in line with his apparent preference not to take himself or his photography too seriously: “The basic theory is: the more rubbish you take, the better the chances of a good photo emerging, so I keep on taking the rubbish.”

The book sketches the outline of Parr’s history, from his introduction to photography—by way of his grandfather, a devoted amateur—to early black-and-white pictures inspired by the work of the American photographer Garry Winogrand (1928-84) and fellow Briton Tony Ray-Jones (1941-72), with Parr’s sense of humour already on display. One image taken at Bolton Abbey shows a grumpy priest in sunglasses appearing to chastise a sheepish young man with his back to the camera—head bowed, hands stuffed into his pockets—the two men subtly divided by a thin line running through the grass. “When I’m taking photographs, I look for the space between things, the relationship between components of the picture,” reflects Parr, “not the thing itself, but how they relate.”

The publication also charts controversy, beginning with Parr’s famous series The Last Resort (1983-85), taken at New Brighton beach in Merseyside, depicting the happy chaos of British leisure time and the messy reality of life as it is being lived (with no shortage of fish and chips). The pictures caused a stir due to their vivid colours—very much against prevailing taste—while prompting accusations of exploiting and poking fun at working-class communities. Parr’s later colour series Small World (1987-94) focused on the spread of tourism around the globe. Its exhibition led to a dismissive fax from the elder statesman of documentary photography, Henri Cartier-Bresson, who told Parr that his work seemed from another planet altogether. Parr promptly responded: “I acknowledge that there is a large gap between your celebration of life and my implied criticism of it […] What I would query with you is, ‘Why shoot the messenger?’”

Parr’s core themes have remained consistent, while maintaining a clear emphasis on picturing the world at its most up to date. Whether capturing Dublin’s first drive-through McDonald’s or the crowded beaches of Argentina; Britain’s Thatcher-era conservatism or the aftermath of Black Lives Matter protests; the numb sterility of North Korea or “the highly competitive world of home-made lemon curd” (as one picture is captioned), photographs, he observes, “tend to organise chaos, to define what we’re doing here”.

Looking back, Parr is clearly struck by how photography itself has altered. “Nowadays you couldn’t take a picture like this, of a kid with no clothes on,” he notes of a photo from The Last Resort, “but back in the early 80s it wasn’t an issue at all. I could photograph freely and no one batted an eyelid.” He is also drawn to how technology has moved on; the final pictures in the book are taken with an iPhone. “A theme in my photography is how things have changed”, Parr suggests. “And they’ve really changed.”

Utterly Lazy and Inattentive provides a welcome introduction to one of Britain’s most significant photographers, offering an insight into how the world has shifted right under our noses. One gets the sense, even now, that Parr has more unfinished business: “there is so much out there I want to photograph,” he concludes. “Okay. Next photo. Which one?”

• Martin Parr and Wendy Jones, Utterly Lazy and Inattentive: Martin Parr in Words and Pictures, Particular Books, 312pp, more than 150 images, £30 (hb), published 4 September

• Rowland Bagnall is a poet and freelancer