When not thinking about carbon nanotube coated electron emitters as a mechanical engineer and PhD student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Alex Kachkine is thinking about art. Kachkine is an avid collector and a self-taught restorer of paintings who combined their two seemingly disparate interests to create a disruptive new approach to art restoration in the form of digital masks.

“I enjoy the concept of rescuing paintings that have been neglected and abused over the years,” Kachkine says.

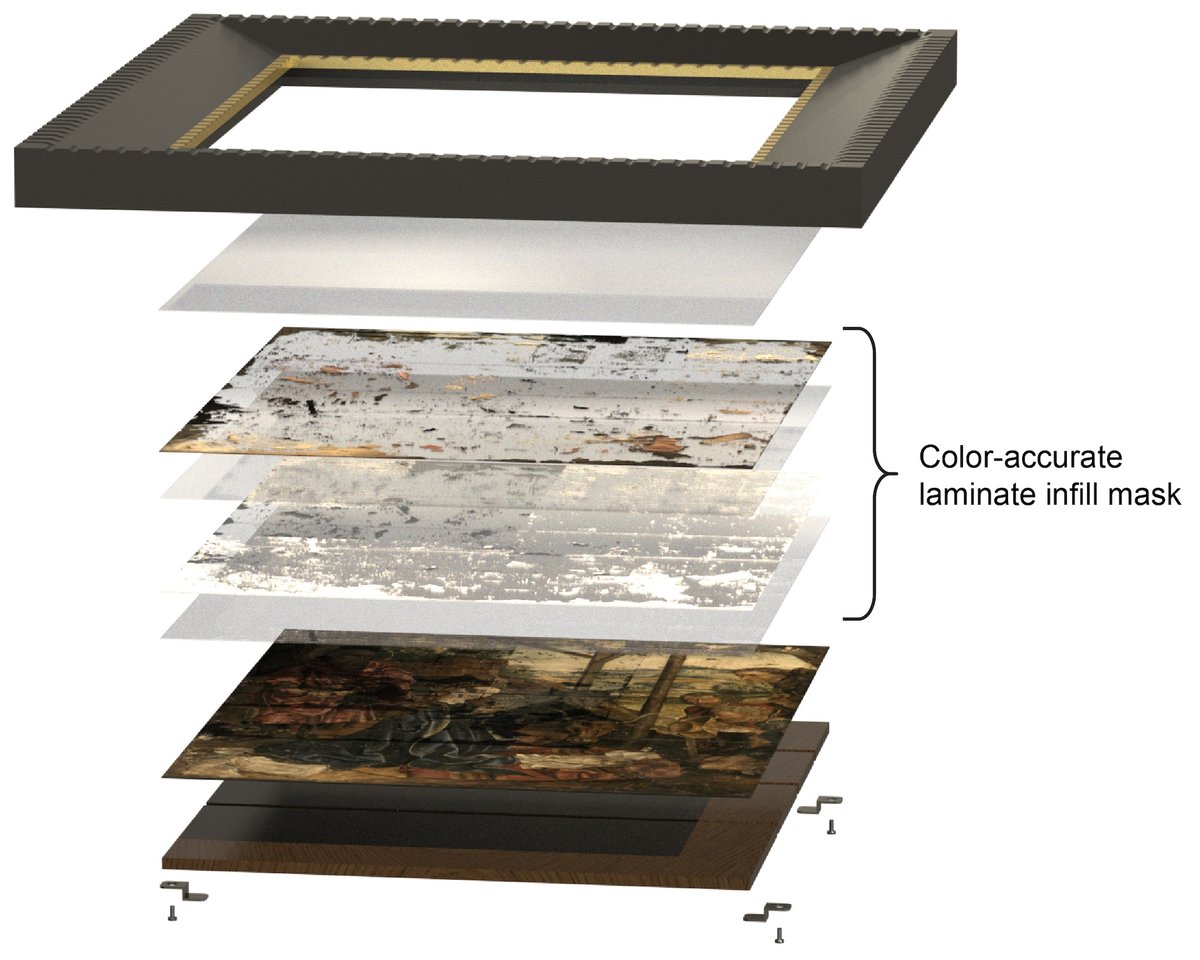

The mask system they developed is a fully removable, precision-printed polymer film with both clear and painted areas that overlay the art, much like a custom graphic wrap used in advertising. While it does not address every conservation challenge, such as remediating mould or stabilising physical damage, it does offer restorers the opportunity to visually reconstruct painted images with the aid of artificial intelligence (AI). Kachkine, who put several years of research and development into this innovation, says that the production of the masks takes only several hours.

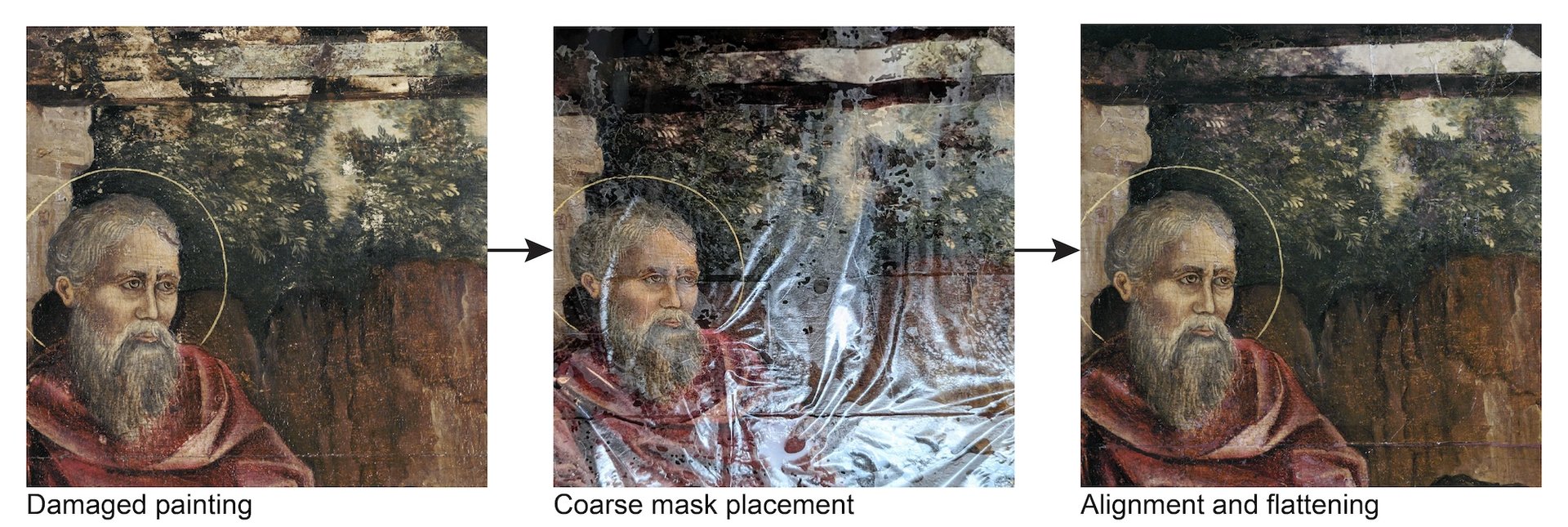

The placement of one of the masking layers atop a damaged part of the painting Courtesy Alex Kachkine

“What I’m seeing this technique being is a way—just a tool in the toolbox—that conservators use for addressing damages in paintings,” they say. “For very heavily damaged paintings, it’s a technique that reduces the time for manual in-painting from many months to several hours.”

Kachkine got the inspiration from their own practice buying and restoring damaged art. “Especially in cases where a painting looks like it has been very improperly stored and it's unclear how it will survive in the future, those are cases where I love to come in and take it and then bring it back into a presentable state,” they say.

At the same time, Kachkine knew that generative AI inpainting tools, already in use for restoring paintings and photographs, had advanced to match the aesthetic context of the original work. And high-fidelity inkjet printers could reproduce these generated images with an ultrafine resolution.

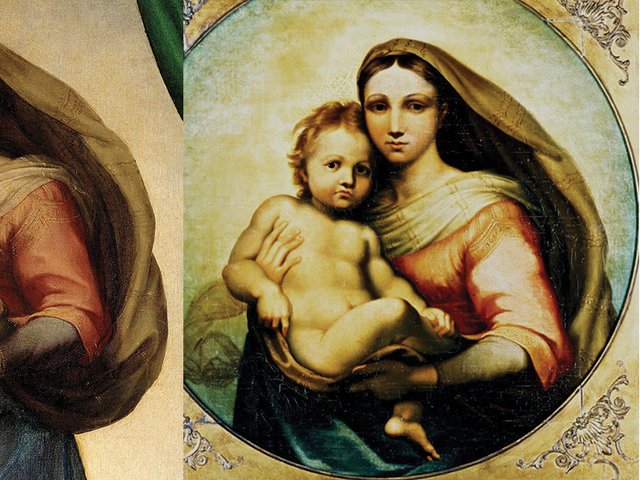

Alex Kachkine's damaged painting before restoration Courtesy Alex Kachkine

To put these technologies to use, Kachkine worked on a damaged oil-on-panel painting from their own collection, a late-15th-century rendition of the Biblical scene of the Adoration attributed to Master of the Prado Adoration of the Magi. The painted image, a nativity manger scene, shows multiple areas of loss including an obliterated infant Jesus and significant edge damage.

Kachkine began with traditional conservation techniques such as cleaning the work and assessing its condition. They next made a high-resolution scan of the painting, which revealed 5,612 areas of loss. Kachkine integrated their knowledge of art restoration with the capabilities of off-the-shelf generative AI software programmes to digitally reconstruct the damaged areas. Kachkine fine-tuned the model to visually preserve the original work while also creating an aesthetically pleasing and cohesive image. Aligning the original and in-painted areas proved to be one of the most challenging tasks, Kachkine says.

The restored version of Alex Kachkine's painting once custom-printed laminate masks were applied to damaged areas Courtesy Alex Kachkine

Kachkine also pushed the boundaries of this digitally-enabled restoration in addressing the extensive area of loss around the head of the infant Jesus. They drew from the Master of the Prado Adoration of the Magi’s similar The Presentation in the Temple (1470-80), from the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, reproducing and digitally transferring the infant’s head and facial features to the mask. All areas of restoration are clearly discernible to the viewer and the polymer film is physically separated from the painted surface via a layer of removable, conservation-grade varnish.

Kachkine’s work has been published in the journal Nature and is part of a movement in the art conservation field to tap advanced technologies for the ever-growing list of restoration projects. They add: “It gives me great hope that conservators are happy to develop these techniques and leverage the developments that have occurred in the modern era. And I’m really hoping that what I’ve done can help them.”