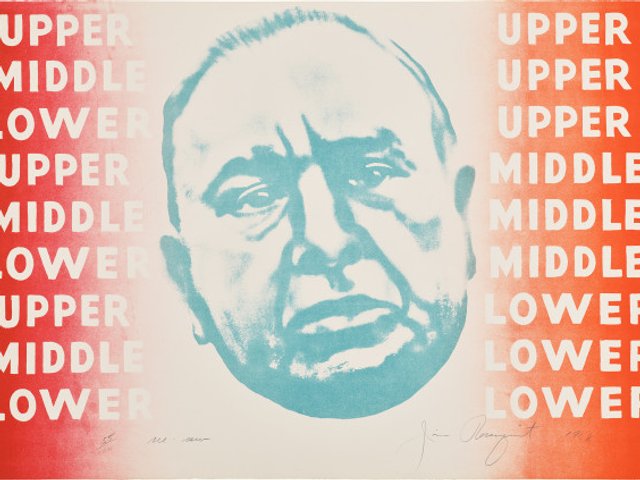

In the 1980s, the pioneering British Pop artist Peter Phillips would sometimes live in his studio for weeks on end. The space was filled with mechanical tools, textbooks, cuttings, comic books, collectable pin-up cards, sketchbooks and even a stuffed tiger, which he had rescued from the back of a museum. By slicing apart, merging and multiplying these sources into saturated, collage-like compositions, he changed the frequency of contemporary art.

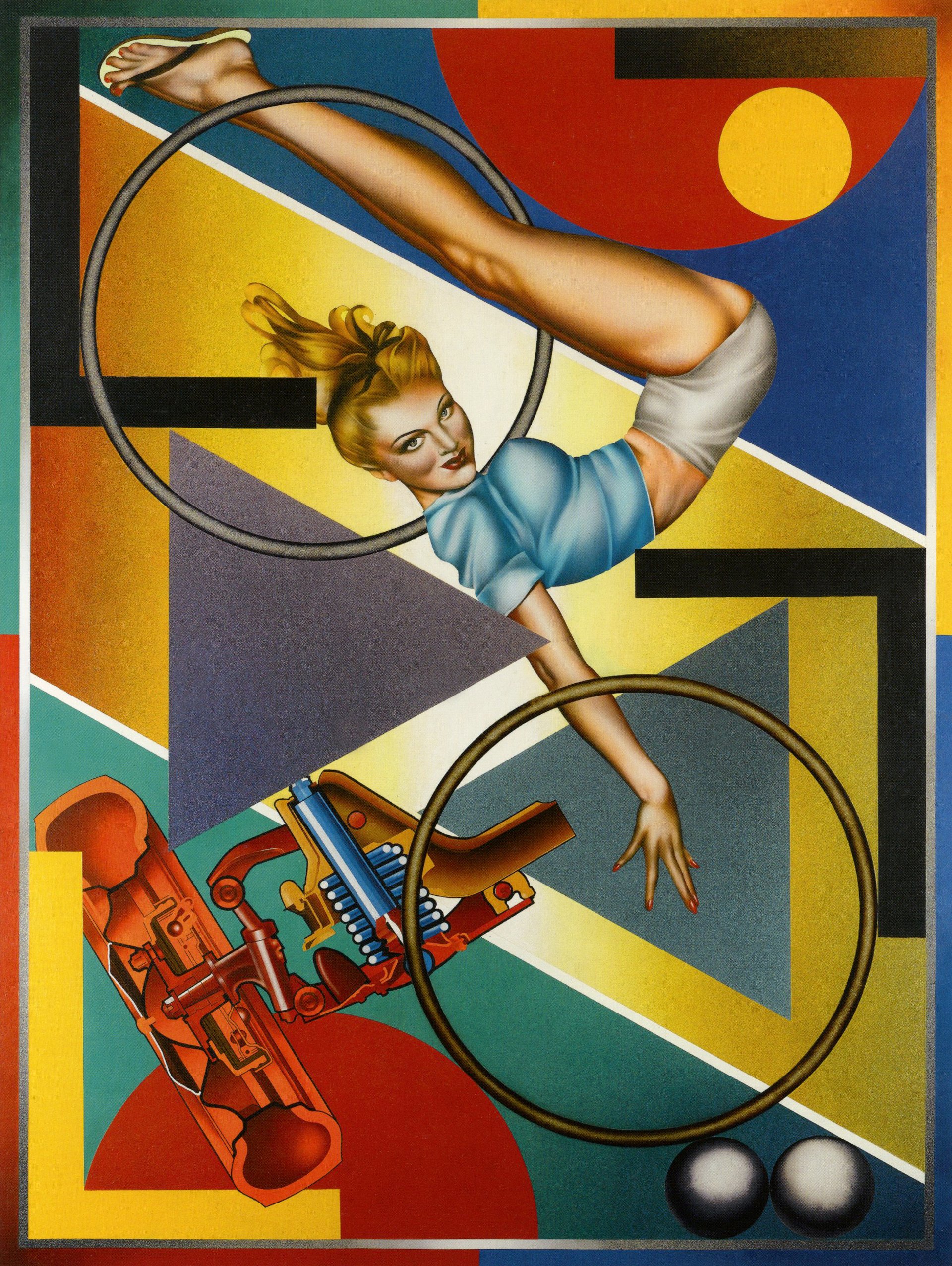

In Ken Russell’s 1962 film Pop Goes the Easel, a self-confident 22-year-old Phillips is seen entering his studio at 58 Holland Park Road, in west London, where a woman is playing with a pinball machine. As the pinball clangs, the camera spans to Phillips’s painting The Entertainment Machine (1961), hanging on the wall. Against flat planes of bold primaries are assembled mechanical parts, targets and piano keys; this huge, grid-like composition acts as a blueprint for the artist’s burgeoning, early 60s, aesthetic.

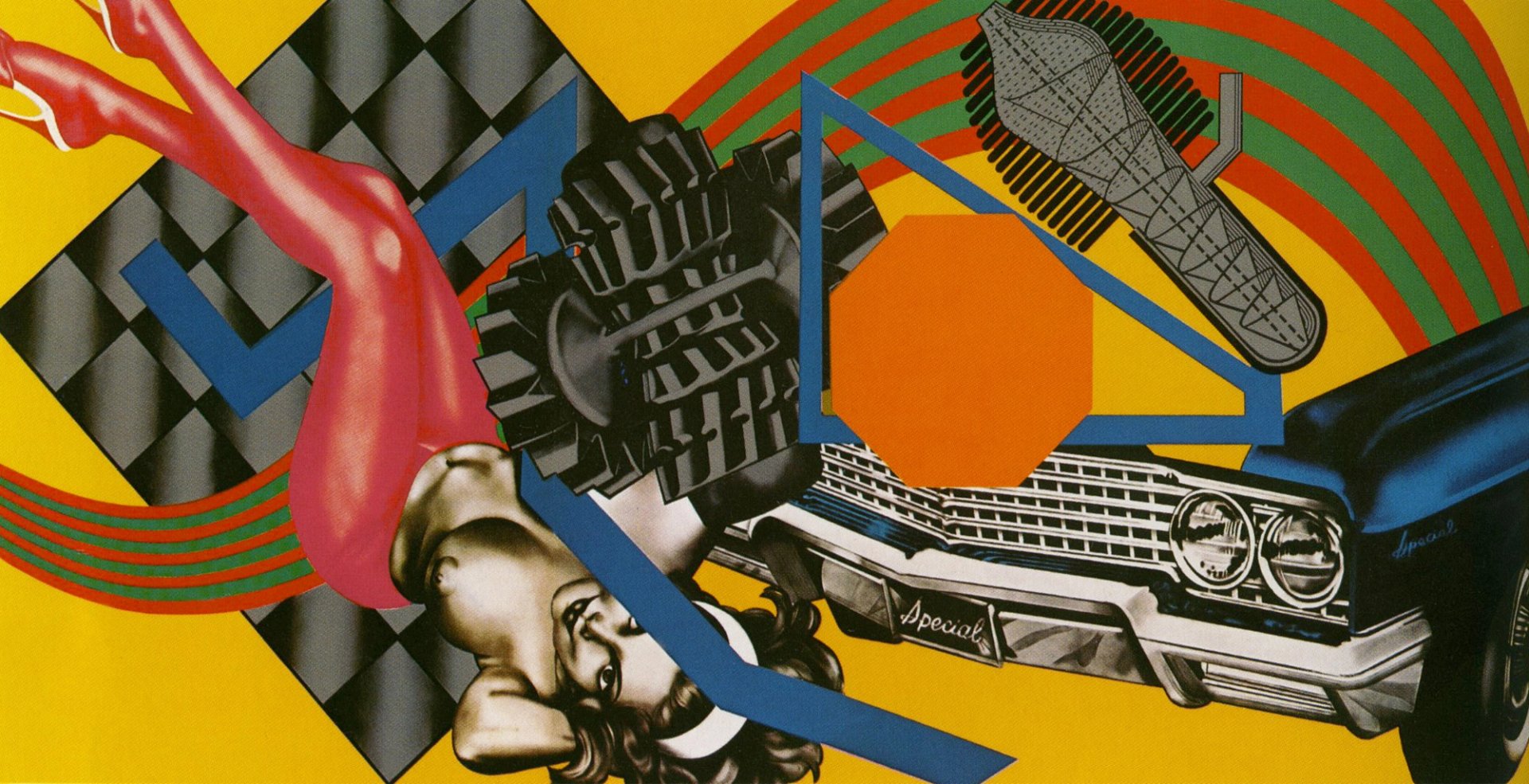

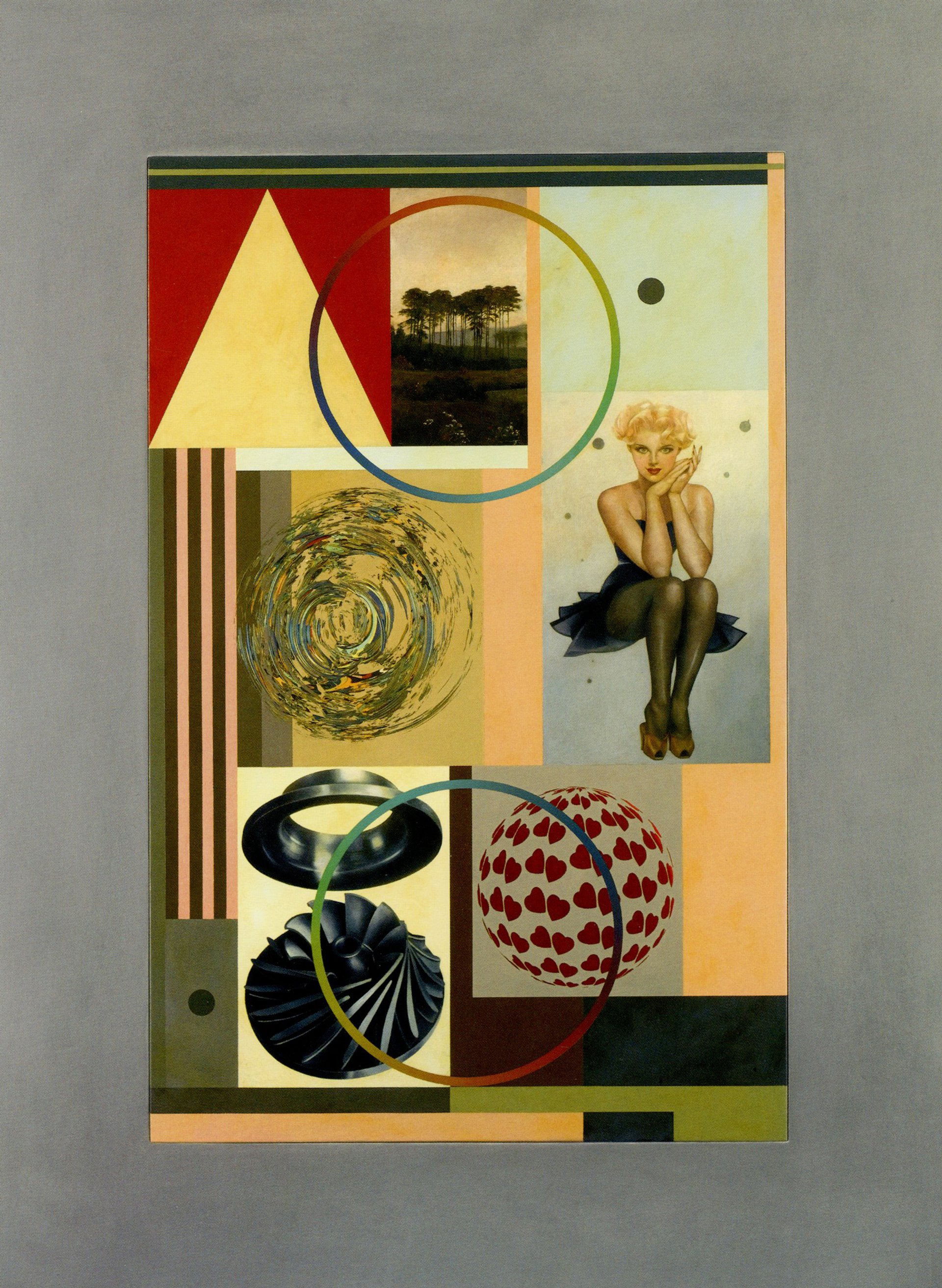

Peter Phillips, Custom Painting No 5 (1965) © The artist. Courtesy of the Phillips family

Defined by the language of industrial design, the painting’s subject matter reflects Phillips’s upbringing in Birmingham, where he was born in 1939 to working-class parents. His father Reginald John Phillips was a carpenter and later made frames for some of his son’s artworks. His mother Marjorie Phillips was employed at the Cadbury’s factory in Bournville. Like other artists from the city of his generation, including John Salt, Phillips made work in response to car manufacturing and garages. Decades after he had left his home city, Philips spoke to me, in a characteristically straight-talking Brummie manner, about the origin of automobile parts in his work:

“I started getting interested in cars because I couldn’t afford one myself. I had friends, in Birmingham, whose family had car dealerships. And they always came around with fancy cars. Because I was an artist, they thought it was cool for me to drive around with them. So I drove around with them. I sat in the front seat… until we picked up girls – which was the whole gesture of it. That’s what you do when you have a car.”

When he was not cruising around the city, Phillips spent time with Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery’s collection of Pre-Raphaelite paintings which he described, in understated terms, as “nice to look at”. He also paid tribute, with sincerity, to his early education: “Art schools in Birmingham gave me my start.”

Peter Phillips, Custom Painting No 6 (1965) © The artist. Courtesy of the Phillips family

At Moseley School of Art, classes in painting, sign-writing, graphic design and technical draughtsmanship had a huge influence on his practice, including the airbrush technique he adopted to imitate sleek commercial illustrations. “The way I handle painting—like a printing process, flat areas of colour—is partly related to the training I got”, he said.

Studying next at Birmingham School of Art and Crafts, Phillips was selected to exhibit two paintings at the 1958 Young Contemporaries exhibition in London. Both Early Shift and The Dispute (undated) depict working class scenes and, looking back, Phillips remarked dryly: “That looks like Birmingham, doesn’t it? Workers on the street…not working.” While his style would change dramatically, he was already drawing inspiration from immediate environments.

But Phillips had aspirations beyond Birmingham and in 1959 he enrolled at the Royal College of Art, in London. Looking back, he recalled this as “a special time”, defined by mutual respect, rather than rivalry, between peers who included Pauline Boty, Derek Boshier, David Hockney, Allen Jones and R.B. Kitaj.

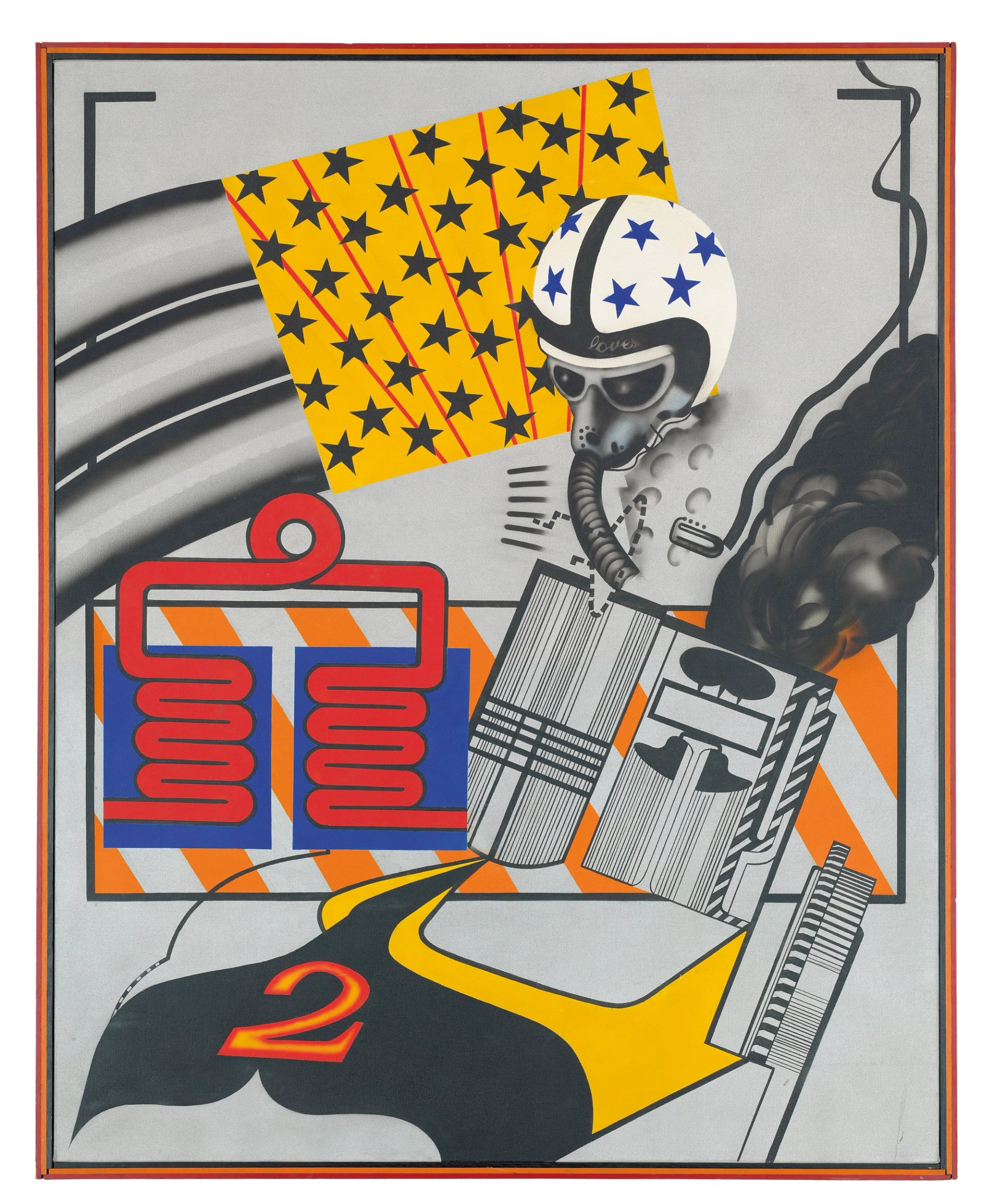

Peter Phillips, Art-O-Matic Riding High (1974) © The artist. Courtesy of the Phillips family

Phillips found the school “very conservative”. His older fellow student Peter Blake has also said of the three-year course: “you had to spend it in the life rooms, drawing or painting from the model.” Around the edges of formal learning, these two became friends, and Blake still thinks of him with “fondness”; sharing a sensibility as working-class artists, they experimented with collage, remixing the fabric of “low” culture into “high” art.

In his early oil and collage on canvas For Men Only—Starring MM and BB (1960), Phillips assembled contradictory symbols: a strip tease vignette, the movie stars Marilyn Monroe and Brigitte Bardot, and a hare leaping from a Victorian board game. This graphic composition shows him releasing images from their original meaning with irony and conceptual power. He was proud to be using “stuff that was familiar to other people, in other words it wasn’t imagery that they expected to come from an artist”.

But when one critic called him “the anti-art enigma”, he was adamant: “I am not anti-art”. Thanks to a scholarship, awarded while studying in Birmingham, he visited Italy on a trip that “really made an impression”. Influenced by pre-Renaissance masters, he adopted their way of organising paintings into storyboards, dividing contemporary images into separate compartments.

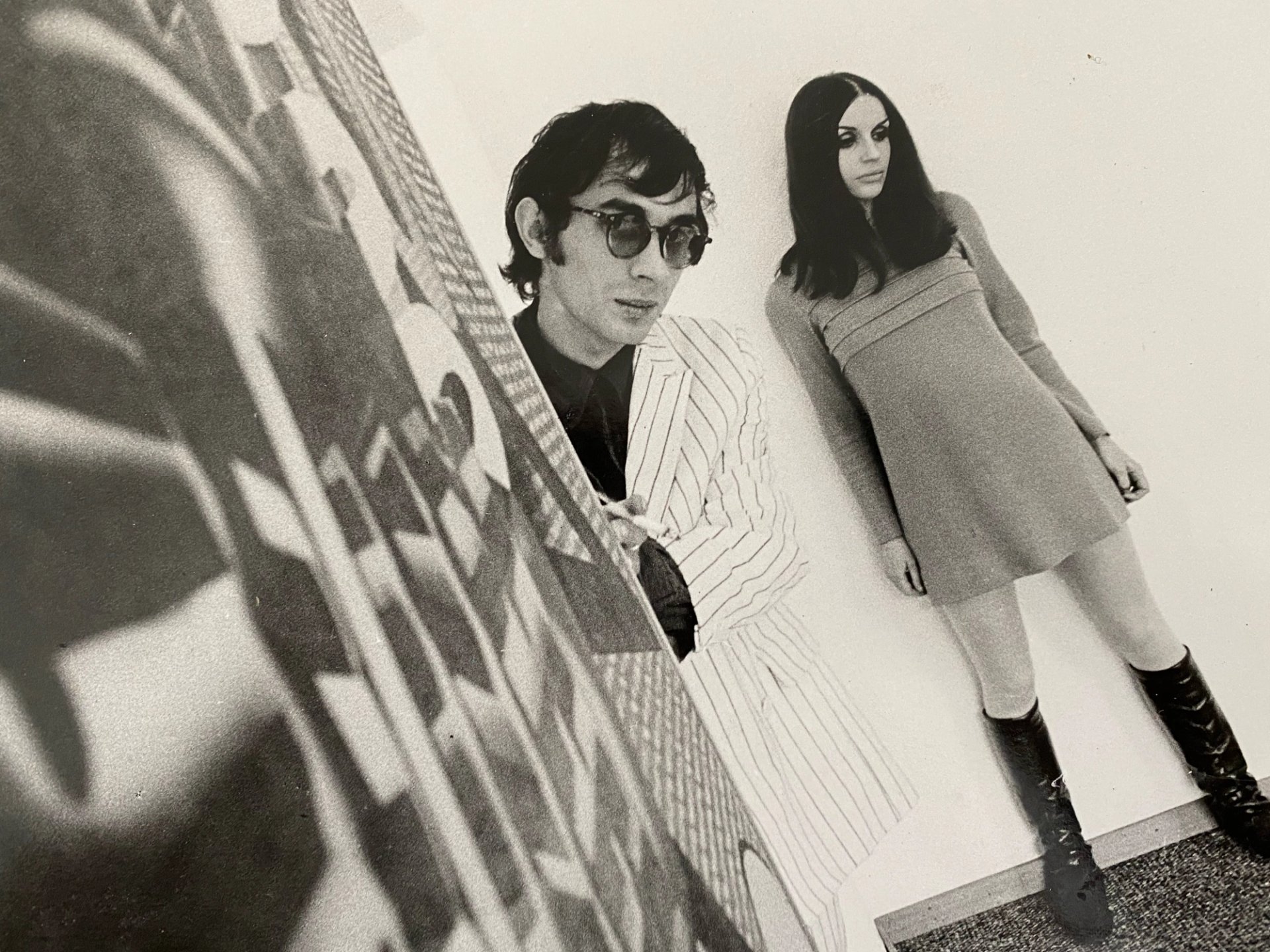

Peter Phillips pictured in the late 1960s with Claude-Marion Xylander, his future second wife Courtesy of the Phillips family

Launching British Pop Art, Phillips organised the influential 1961 Young Contemporaries exhibition at the RBA Galleries, featuring work by Boshier, Jones, Hockney, himself and others. Building on this momentum, Phillips showed at the 1962 Young Contemporaries, in 1963 was represented at the Paris Biennial, and the following year participated in Nieuwe Realisten at Gemeentemuseum in The Hague. Phillips was, as Peter Blake says, “a key element in Pop Art in the 60s”.

The US was also calling and, thanks to a Harkness Fellowship in 1964, Philips was able to live his American Dream. Based in New York for two years, he exhibited alongside Andy Warhol, James Rosenquist and Roy Lichtenstein, while taking road trips in a Chevy with his friend Jones. Of all his British contemporaries, Phillips became closest to the US Pop Art artists, adopting their commercial iconography of guns, uniforms, patriotic pin-up women, and stars for series such as Gravy for the Navy (1963).

When his close friend the US-based British curator and critic Lawrence Alloway coined the Pop Art label, Phillips accepted it willingly. Later, Alloway was among 137 cultural players that Phillips interviewed for a collaborative project with the artist Gerald Laing: questioning what would make an “ideal art object”, Phillips and Laing transformed their results into an aluminium and neon sculpture, Hybrid (1966). They had taken Pop Art off its easel, exhibiting this robotic work in New York.

Peter Phillips, In Claude's Memory (2003) © The artist. Courtesy of the Phillips family

From 1964 to 1967 Phillips was married to Dinah Donald, with whom he had his first child, Tiffany, before the pair divorced. In 1970, Phillips re-married: his second wife Claude-Marion Xylander was a high fashion model who graced the covers of magazines including Elle. Owning a shop called Galaxy in Switzerland, she helped Phillips network with collectors, acting as his studio and business manager, until her death from cancer in 2003. Their daughter, Zoe, was born in 1981.

Phillips’ first solo show was at London’s Waddington Galleries in 1976, and his travelling retrospective opened at Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery in 1983. But never one to rest on his laurels, Phillips continued to develop by diversifying his sources. Fascinated by science and technology, like Eduardo Paolozzi, whom he met in 1964, Phillips transformed images from Scientific American magazine into a series of futuristic-looking screenprints, PNEUmatics, in 1968.

Then, during the 1990s, cut-out machine parts floated into mysterious, more subtly-toned spaces, assuming a lyrical quality in his oil and collage on paper works such as Night Dance (1990), and Seesaw (1990-91). During the 2000s, Phillips used computers to research, enlarge and work from more complex images. Incredibly disciplined and methodical as an artist, as his daughter Zoe Phillips-Price says, “he would spend countless hours perfecting intricate details, often wearing jeweller’s glasses to ensure every stroke was placed with intention”. A diagrammatic quality came to define paintings such as his Africa Twirl (2009-10), commissioned for the 2010 FIFA World Cup, held in South Africa.

Phillips with his dog Bella and Art-O-Matic Riding High (1974) at the Phillips Gallery, Noosa Hinterland, Queensland, around 2016 Courtesy of the Phillips family

Never one to chase trends, Phillips “actually liked to buck them”, says Phillips-Price. “Once his early work became widely embraced, it no longer felt novel to him. He was quietly amused by the idea of ‘fitting in’.” Escaping the London-centric art world in the late 1960s, Phillips and his wife Claude lived in Zurich, Switzerland, where their daughter was born, before moving to Mallorca in 1986. Phillips bought land in Costa Rica in 2008. In 2016 a Distinguished Talent Visa allowed Phillips to settle with his daughter in Australia, where he opened a gallery, remaining there until the end of his life.

For over 60 years, Phillips painted peripheries and stark visual juxtapositions, which mirror his personality. He was intensely focused and serious, yet full of wit and sarcasm, deeply introspective, but also someone who enjoyed being seen, as his family remember him. Early success meant that he could paint for himself, and he always rebuffed questions about “legacy”. But it was by reaching inside the machine, blending everyday iconography with classical composition, that he manifested Pop Art, creating a continuum for other artists to experiment with. In his memory, the artist’s family has established The Peter Phillips Foundation.

Peter Phillips; born Birmingham 21 May 1939; married 1964 Dinah Donald (one daughter; marriage dissolved 1967), 1970 Claude-Marion Xylander (died 2003; one daughter); died Sunshine Coast, Queensland, Australia 23 June 2025