In a corner of New Mexico’s Site Santa Fe art centre—currently featuring the 12th Site Santa Fe International: Once Within a Time (until 12 January 2026)—is a display case of painted terracotta figures by the New Mexico-based artist Helen Cordero. Inspired by the folklore of her people, the Cochiti, they feature a grandfather figure, his eyes closed and mouth open, and a group of small children perched on his shoulders and arms listening to his tale.

Storytelling is at the heart of this year’s biennial, with its main display at the Site building in the Railyard Arts District of Santa Fe and additional pieces in other locations around the city—a dozen of them, from inside museums to a former foundry and in storefronts. “I was doing a lot of research about Indigenous art, like the Pueblo artists,” Cecilia Alemani, the director of the High Line in New York and this year’s guest curator for the International, tells The Art Newspaper. “And Cordero has been so influential. She was probably the first artist I thought about including, because I knew it was going to be a show about storytelling.”

The exhibition’s title, Once Within a Time, references the opening line of many a folk story. The show features more than 70 artists and 27 “figures of interest” (both living and historical) presenting the artist as storyteller, conveyor and creator of narratives—like that of the Cochiti grandfather.

Installation view of Once Within a Time, with Helen Cordero’s Storyteller figurines (left) and Simone Leigh’s Untitled (2025)

Site first launched its biennial in 1995. In 2021, after a pause in programming due to the pandemic, Louis Grachos arrived as the art centre’s executive director and took time to rethink the project. He had worked there previously, running it from 1996 to 2003, and knew that finding the right curator for the biennial was crucial. “I was really impressed by the Venice Biennale that Cecilia curated, The Milk of Dreams,” he says, so he invited her to do the honours at Site.

Fortunately, she accepted, and Grachos is delighted with the results. “Cecilia captured the mission beautifully in her exhibition by selecting numerous artists who live and work in New Mexico,” he says.

Once Within a Time also includes artists from elsewhere around the country and the globe, all of whom have a connection to New Mexico or storytelling. For example, the Lebanese artist Ali Cherri’s elegant short film about an exhausted soldier in Cyprus, The Watchman, has been placed in the auditorium of the New Mexico Military Museum. In the film, a soldier begins to see lights moving in the distance—are they real, or just his prolonged anticipation of war?

Installation view of Once Within a Time, with Penny Siopis’s Atlas (2020-ongoing) and D.H. Lawrence’s erotic paintings (1926-29)

For Alemani’s part, she wanted to work with Grachos and in New Mexico. “I think it's an interesting moment for doing exhibitions like this in the world,” she says. “As a visitor, I want to go see a show that can only happen in that place. Even if fewer people might see it, the idea that you're doing a show that speaks about a place, a people and a community is very relevant. I wasn't interested in doing a show of trophies or blue-chip art that you could see everywhere.”

While there are a few blue-chip artists included here (Simone Leigh, Frederick Hammersley), most of the others are regional or under-the-radar. They employ a range of mediums, including painting, sculpture, photography, video and installation. What is most surprising is how many creative people passed through New Mexico and made work there—such as the novelists D. H. Lawrence, with his series of blurry and erotic paintings, and Vladimir Nabokov, an avid lepidopterist who made a series of detailed butterfly drawings. These literary giants’ visual works are shown in the main exhibition.

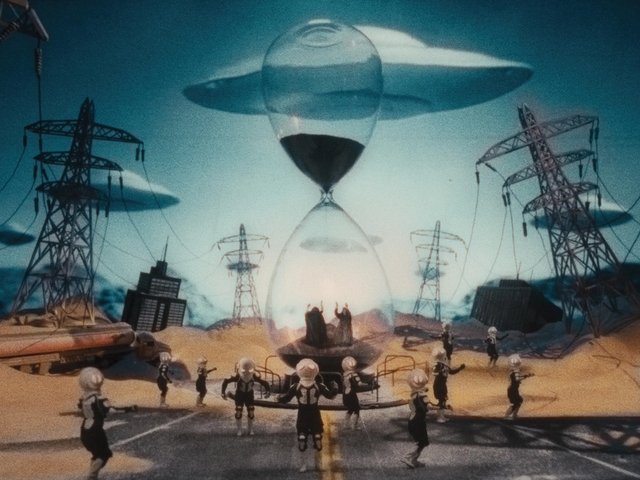

When Alemani was appointed curator a year and a half ago, she immediately started doing research—reading what she could find, visiting local museums and meeting artists. Once Within a Time is the title of a 2022 film by Godfrey Reggio, which is on view at the biennial. As a teenager, Alemani had fallen under the spell of Reggio’s experimental Qatsi trilogy films—starting with Koyaanisqatsi: Life Out of Balance (1982), which pairs a propulsive stream of images with a propulsive Philip Glass score. During Alemani’s research, she discovered that Reggio was a long-time Santa Fe resident.

Daisy Quezada Ureña’s Past [between] Present (2025) at the New Mexico History Museum’s Palace of the Governors

Some of Alemani's selections are clearly connected to the Southwest, such as Cordero's figures, the etchings of M. Scott Momaday and Pablita Velarde’s paintings. The artist Will Wilson uses photography to highlight abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo Nation’s land, built before the dangers of radiation were fully known. Meanwhile, Daisy Quezada Ureña uses conceptual modes in a historic location, the Palace of the Governors, which is part of the New Mexico History Museum.

“What do we need to be having a conversation about in this public sort of forum and space?” Quezada Ureña said during a presentation at Site. Her answer was that the conversation should "revolve around colonisation, which is sort of the basis of that building, right? It was built in 1610, when the Spanish arrived.” The legacy of Spanish conquest is rife with brutality and coercion. She has filled one room with both borrowed and created objects placed into display cases suspended at different heights from support poles. In one, three antique pistols suggest how the Southwest was won—with violence. In another, she has placed porcelain pieces onto an antique scale, one with an image-transfer of an elder’s hand, the other a child’s hand. She was trying to convey “one needing the other, like elder and youth relationships", she says.

Moving pictures are an especially strong component of the International this year. One of the early favourites among Site visitors has been Compound Eyes of Tropical (2024) by the Taiwanese artist Zhang Xu Zhan, who wrote and directed a stop-motion short made with paper-mâché puppets and scenery telling a story based loosely on fables about people and animals trying to make a river crossing. Located on the lower level of the Museum of International Folk Art, the video installation is immersive. with walls and ceiling covered entirely by newspapers twisted into batons lined up side by side.

Zhang Xu Zhan’s Compound Eyes of Tropical (2024) at the Museum of International Folk Art

The film features a mouse-deer—representing the Taiwanese people, says Zhang—attempting to cross a roiling river filled with snapping crocodiles. “He’s a bit of a performer,” says the artist of the character, so the mouse-deer dances back and forth over the backs of the crocodiles to a hypnotic beat. “The music is made by drums, Indonesian gamelans and a bit of electronic music,” says Zhang, who once had a residency in Indonesia. The project took him and his team three years to complete, and it was shown on the High Line earlier this year. In Santa Fe, the work is accompanied by a selection of figurines used in funereal and Day of the Dead celebrations in cultures around the world.

It may be surprising that Santa Fe, a small city of 90,000 people, can support an international exhibition of this scale. Grachos points out that the region has long attracted artists of all kinds—Georgia O'Keeffe and Agnes Martin, who are not included in this year's biennial, come to mind.

“I think it's a place that attracts creative people,” Grachos says. “The great physical beauty of New Mexico, the legacy, the mythologies around Santa Fe. The quality of light in the sky is so inspirational and energising. It feeds the creative instinct. When our founders thought of Site Santa Fe, they envisioned an exhibition that would have the richness of context of place but also bring an international discourse to our community and connect artists and curators. Cecilia has done that masterfully.”

- 12th Site Santa Fe International: Once Within a Time, Site Santa Fe, New Mexico, until 12 January 2026