Although Thames & Hudson has for seventy-six years been one of the most admired imprints in international illustrated book publishing, the man who steered its fortunes since he inherited the company almost sixty years ago was much less well known. Thomas Neurath never sought publicity for himself. He did not conform to many of the preconceptions about a great publisher: he avoided long lunches if he could (he had no head for alcohol) and—since he invariably had a packet of cigarettes to hand—his dislike of parties deepened after it became socially unacceptable to smoke. His life was almost wholly absorbed by the firm founded in London in 1949 by his Austrian émigré father, Walter Neurath, and German stepmother, Eva Feuchtwang. Although he may at first have had conflicted feelings about taking on responsibility for Thames & Hudson while still a very young man—following Walter’s early death in 1967—he brought a single-minded energy and intellectual bravura to the task of developing the firm’s lists, editorially, technically and commercially. His chief monument is the quality of the books published by Thames & Hudson, but the fact that it remains a wholly independent family firm is almost as impressive.

Walter Neurath and his wife, Marianne Müller, a schoolteacher, escaped Vienna with some difficulty after the Anschluss. As a Jew who had been the manager of an anti-Nazi publisher, he was doubly a marked man. Their first child, Constance, was born in 1938, followed two years later by Thomas. Walter had been given a job in London by a fellow Austrian refugee, Wolfgang Foges, in a firm called Adprint, which circumvented wartime paper shortages by packaging – that is, taking books up to the stage of printing – for other publishers. In 1950 Marianne died and three years later Walter married Eva, a former colleague in Adprint, having sunk both their savings in founding a new firm, Thames & Hudson, named after the two rivers to reflect its ambitions to publish on both sides of the Atlantic.

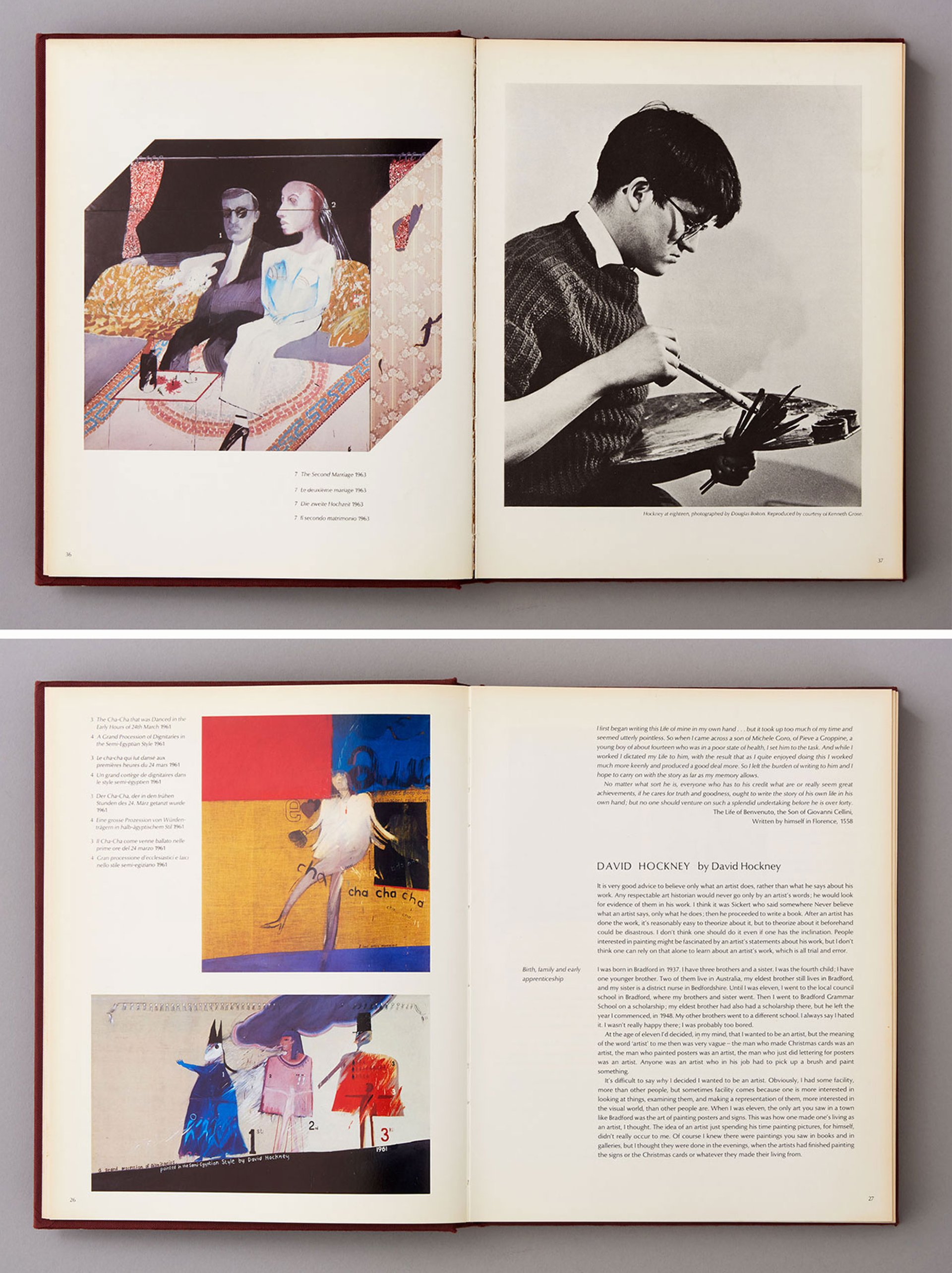

Thomas resembled his father in important ways: both were emotionally reticent men who combined beaming charm with an explosive temper. Life in the Neurath household in Highgate was left-leaning and high-minded. The remnants of the family’s collection of works by such painters as Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele hung on the walls—the rest had been sold to help support the new firm—and there were visits from artists who formed the subjects of its books, from Barbara Hepworth to Sidney Nolan. This nurtured Thomas’s inexhaustible curiosity about art and images. Close relationships with artists were to be an important part of his publishing career, notably with David Hockney, whose collaborations with Thames & Hudson extend from David Hockney by David Hockney, edited by Nikos Stangos, which when published in 1976 played an important part in establishing the artist’s international celebrity, to the catalogue of Hockney’s great retrospective this year at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris.

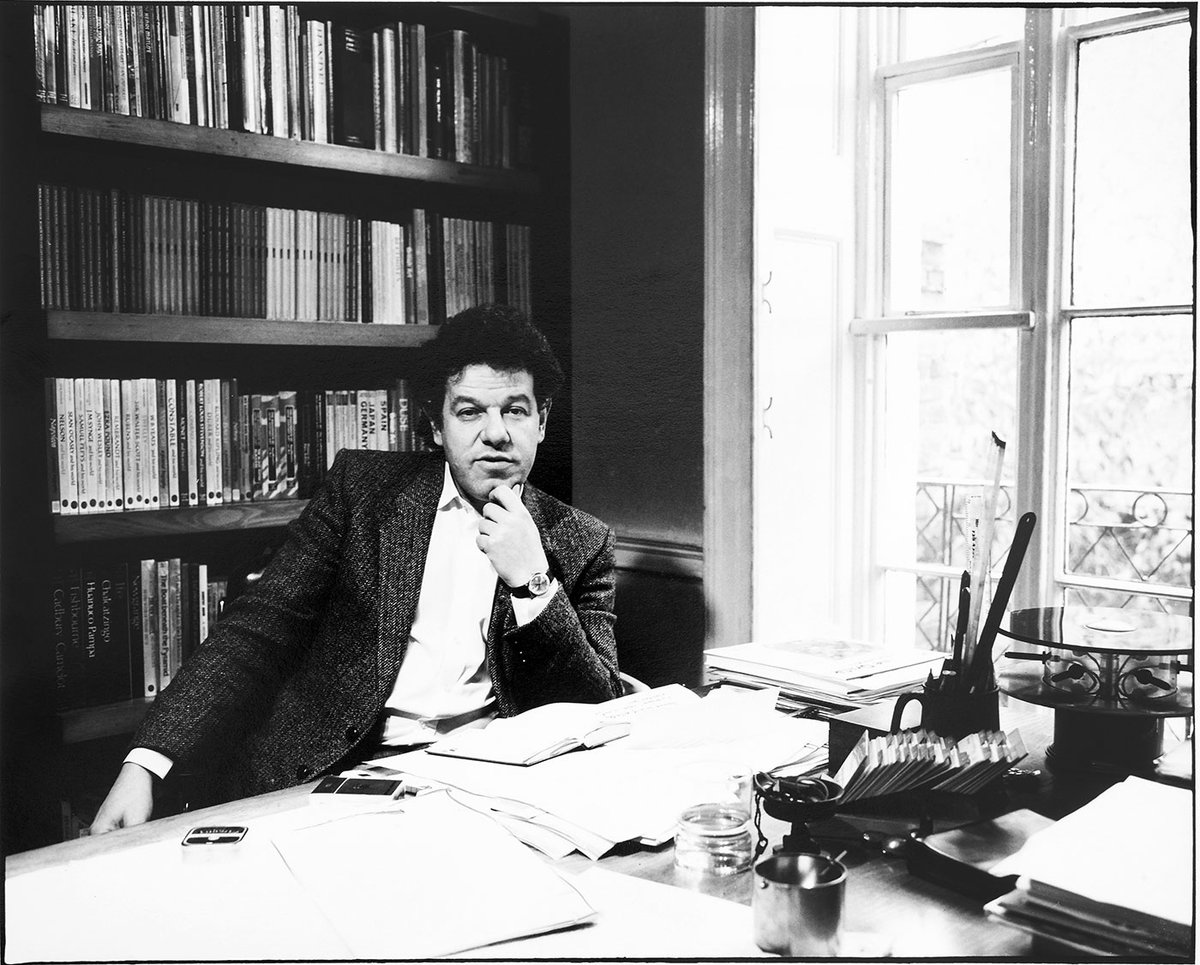

Thomas Neurath: a particular enthusiasm for photography and a concern for the function of the picture caption Courtesy: Thames & Hudson

Whenever he could, Thomas combined business abroad with exploration of museums and galleries. One colleague summoned to Thomas’s office after he had returned from a trip to Karlsruhe expected to discuss the deals that had been made but was given instead an excited account of a visit to an exhibition of sound art at the ZKM Media Museum: "Can you imagine? A museum of sound!” Thomas was once heard to lament "I’ve run out of walls"—talking of the home in north London he shared with the Swedish-born jewellery designer Gun Thor, whom he married in 1962, and their two daughters, Johanna and Susanna—but he never stopped compulsively buying books.

Thomas Neurath’s cosmopolitanism belied his conventional English education. Charterhouse was followed by Archaeology and Anthropology at St John’s College, Cambridge, but although he had a deep interest in both subjects, he left without taking a degree. After absconding abroad—Walter is said to have used private detectives to track him down—Thomas was brought back to work as an editor in Thames & Hudson’s Bloomsbury offices in 1961. He was moulded for the succession, with an unhappy stint working for a publisher in Israel and a very happy period in Paris as an intern with the French publisher Éditions Arthaud. Boarding at the Beat Hotel, he soaked up the city’s bohemian intellectual culture, and ever afterwards thought of the Left Bank as in some sense home. His opening of an office for Thames & Hudson in Paris in 1989 was the fulfilment of a long ambition. There was a streak of the beatnik in his make-up. He had, for example, a weakness for the beliefs about leylines and earth mysteries promulgated by John Michell, whose books be published, to the annoyance of some of the authors on the firm’s distinguished archaeology list.

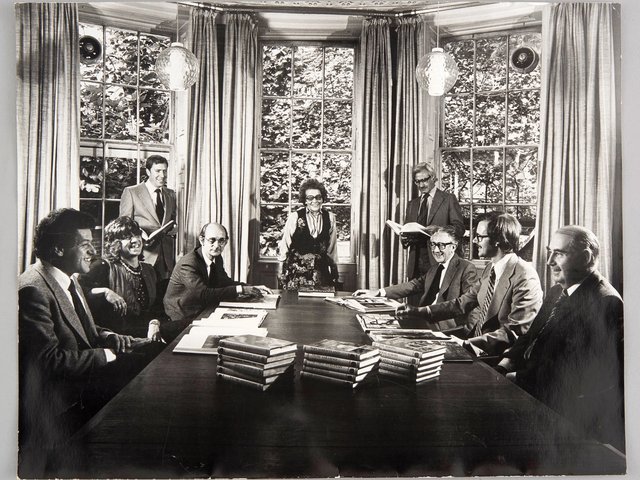

Walter’s death at the age of only sixty-three transformed Thomas’s life. Eva assumed the role of Chairman (her preferred term), Thomas became managing director and Constance was appointed head of the design department. This was a more equal distribution of responsibilities than it would have been in other publishers. Ever since the days of Adprint, the ideal for Walter and Eva, and now Thomas, was the integration of text and pictures—not only physically, on the page, itself unusual in mid-century publishing, but also intellectually. Both words and pictures are important individually, but the success of a book, they believed, depends on the way they work together. Interviewing a candidate for an editor’s job, Thomas would ask not about their language skills (although those were important) but what they thought made a good spread—the fundamental component of publishing on the Thames & Hudson model—and what was the function of a caption?

A concern for the integration of text and images: two double-page spreads from David Hockney by David Hockney (1976), edited by Nikos Stangos and published by Thomas Neurath and Thames & Hudson Copyright David Hockney / Thames & Hudson

Adprint had taught the Neuraths the commercial advantages for Thames & Hudson of publishing books in series, most famously the inexpensive black-spined World of Art paperbacks (eventually numbering some 300 titles), which were a pioneering expression of a desire to democratise access to the arts. Commercially, however, the firm’s long-term fortunes depended on publishing books for the global English-language market simultaneously with editions in French and German, and often Spanish, Italian and other languages as well. Thomas inherited and enlarged skilled teams, often European in origin, in book-production and picture research as well as editing and design. Unusually, Thames & Hudson liked to keep its expertise in house rather than rely on freelancers. Thomas was a demanding employer but also a protective and even possessive one who could appear visibly distressed when told that a promising young employee was leaving for another job.

Whereas his father had thought of art in elevated terms— great paintings, sculpture and architecture—Thomas had a more inclusive vision of visual culture. Photography was a particular enthusiasm, and he made it a highly profitable part of the list (notably through collaborations with the Magnum photographic agency), as he did fashion, although indifferent to clothes for their own sake. He deplored the widespread assumption of otherwise educated people that there was something frivolous about “picture books”. When as a young editor at Thames & Hudson I commented that I was looking forward to the reviews of a photography book I had been working on, he told me with a sigh that I would be disappointed: “The Times Literary Supplement will give a whole page to a novel by an unknown writer, but when we publish a major monograph on Cartier-Bresson all we get is a picture and a caption.” That was said forty years ago. Most media outlets now regard illustrated books much more seriously, and for that Thomas Neurath can take much of the credit.

Thomas Neurath, born Brackley, Northamptonshire, 7 October 1940; managing director, Thames & Hudson 1967-2005, chairman 2005-21; married 1962 Gun Thor (two daughters); died London 13 June 2025.