An inoperable silvery-blue bus is parked at a dying Greyhound Lines terminal in Cleveland, Ohio, and it is becoming a beehive of activity.

Its presence has stirred up “so many different emotions”, says Robert Louis Brandon Edwards, an historian, artist and preservationist based in Cleveland. Last year, he bought the bus, which was manufactured for Greyhound in 1947, and had it trucked from a Pennsylvania junkyard to Ohio.

The bus station, built in 1948, is a Streamline Moderne masterwork by the architect William Strudwick Arrasmith (1898-1965), with hairpin curves and silvery-blue tiles resembling the fleet that once passed through it. The station will shutter late this year as Greyhound sheds its real-estate portfolio amid industry decline. Plans are afoot to recycle the station into public space for its new owner, Playhouse Square, an adjacent nonprofit compound of century-old performance venues.

Edwards, in collaboration with Playhouse Square, is converting his vehicle into a museum of the Great Migration—when, between approximately 1910 and 1970, millions of African Americans moved out of the rural South to the Northeast, Midwest and Western US. With exhibitions and virtual-reality experiences, the new museum will convey what people endured on their trips northward, escaping from Jim Crow segregation and brutality.

Edwards and his Greyhound Photo: Leo Michael Nash

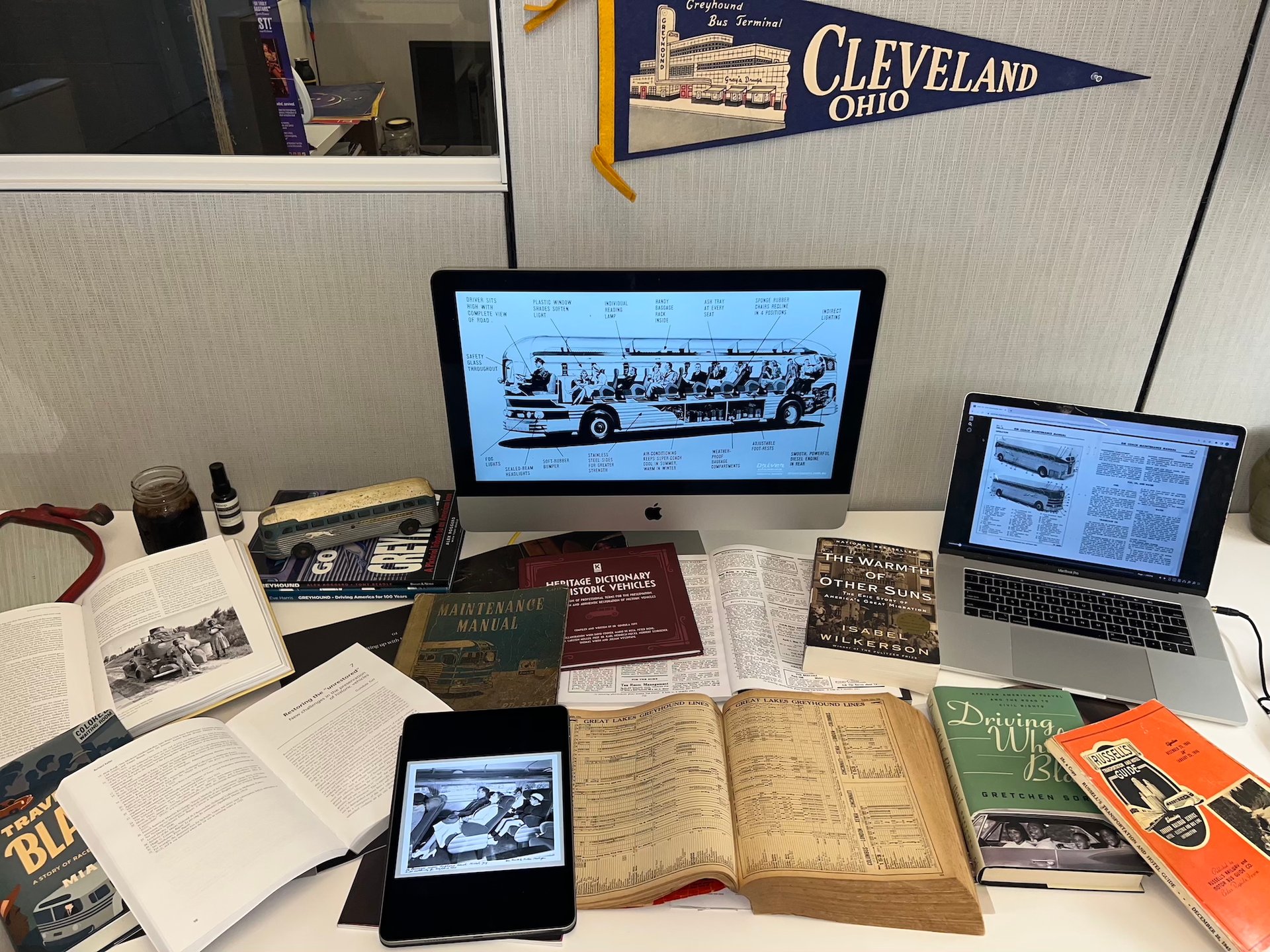

Edwards is gutting the bus’s interior (in the 1970s, it was turned into a home on wheels with an orange kitchen, bathroom and sleeping quarters), while giving lectures and bus tours. He is amassing artefacts—such as Greyhound route maps, timetables and advertisements—and interviewing veterans of Great Migration passages and their families. He is even documenting reactions from perplexed travellers and workers to his bus, berthed in the station’s back lot.

One frequent question: “Is this the bus that Rosa Parks rode when she was arrested?” (No, that one is restored and parked indoors at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.) One frequent comment: “I never thought about how my ancestors got to Cleveland. It might have been on a bus like this; I wonder if there is anyone left to ask.”

Black passengers in the mid-20th century were typically crammed into buses’ dimly lit back rows atop grinding hot engines, Edwards says. They risked being harassed, assaulted, dragged away or worse. They brought along stockpiles of their own food, rather than hoping that roadside restaurants would welcome them. “They didn’t know which places were safe for them to use,” he adds. “Greyhound bus stations, to me, are like Ellis Island.”

The project, which is part of Edwards’s Columbia University doctoral studies in historic preservation, was inspired by his own family’s odyssey. In 1963, his grandmother Ruby Mae Rollins moved by Greyhound bus from Fredericksburg, Virginia, to Manhattan with her small daughters Cindy and Linda (Edwards’s mother). Cindy Rollins, who has retired from a career in education in New York and moved back to Fredericksburg, says that she remembers her mother supplying comfort food at the back of the bus: “She fed us with her chicken from home.”

Edwards’s project is part of his Columbia University doctoral studies in historic preservation Photo: Leo Michael Nash

In 2022, Edwards started wondering whether any bus used during the Great Migration survived, for him to restore and share its story. His thinking was along the lines of: “Hey, that’s a crazy idea, I should probably pursue that,” he says. When a suitable antique surfaced in Pennsylvania, priced at $12,000, he bargained the junkyard owner down to $5,500 in cash. (Shipping the vehicle by flatbed truck to Cleveland, with a pitstop at Cindy Rollins’s driveway in Virginia, cost $7,000.) Many original bus components survived the 1970s redo, including the back bench used by Black riders and the destination sign over the windshield made of a roll of black-and-white fabric.

Last year, Playhouse Square paid about $3m for the Greyhound terminal, and Edwards asked to shelter his bus there. The nonprofit’s team jumped at the chance to incorporate his compelling project into reuse plans for the station, says Craig Hassall, Playhouse Square’s president and chief executive: “The synchronicity is palpable.” Programmes and displays at the converted building may explore related aspects of Ohio’s history, including its 19th-century stations for Black escapees on Underground Railroad lines and the Jazz Age performers and ticket-holders who took buses to reach Playhouse Square’s gilded neoclassical theatres.

Regennia N. Williams, an associate curator at the Cleveland History Center, says that Edwards’s surprising bus-in-progress is sparking admiration for its tenacity. He has become known locally as “a bit of a folk hero,” she says. This autumn, the centre’s new gallery dedicated to the area’s African Americans will cover topics including Great Migration arrivals.

Among other institutions exploring the subject is the Marin City Historical and Preservation Society in northern California, which organises travelling exhibitions about the region’s Black workers who arrived in the 1940s for jobs at military shipyards. The society displays a restored 1940s Greyhound bus (owned by the nearby Pacific Bus Museum) alongside images and artefacts such as battered leather suitcases and a Greyhound ticket poster.

Edwards gutting the bus’s interior—it had been turned into a home on wheels in the 1970s Photo: Leo Michael Nash

Felecia Gaston, the Marin City society’s founder, has recorded Black residents’ memories of taking one-way trips out of the South in the 1940s. They packed shoeboxes for the road with durable foodstuffs, like hard-boiled eggs, fried chicken, pound cake, peanuts and raisins. “And they always brought enough food to share with other people,” Gaston says. “There were always people taking care of each other, looking out for each other.”

In Cleveland, Greyhound and Playhouse Square workers “are definitely looking out for the bus” when Edwards is not onsite, he says. Edwards is scouting for vintage seats and other vehicle parts aided by the Bus Boys Collection, a team of dealers and restorers in Minnesota. In the virtual-reality experiences that he is developing for bus visitors, video and audio will represent Jim Crow-era interactions among passengers and drivers.

As Edwards strips away the bus’s 1970s accretions, he has not yet tried to unroll the fragile fabric destination sign over the driver’s seat. It has been paused at the same word since it was mouldering in Pennsylvania: “Special”.