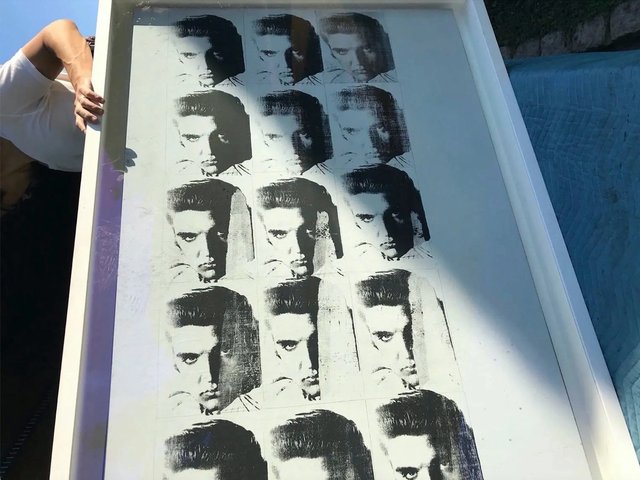

The long-running legal dispute between the billionaire collector Ronald Perelman and his insurance companies has finally reached trial. At the heart of the case are five paintings, allegedly worth over $410m, by Cy Twombly, Ed Ruscha, Andy Warhol and others, which Perelman claims were significantly damaged in a 2018 fire at his East Hampton estate.

Though the works were not physically destroyed, Perelman argues they suffered an intangible loss of value—what he famously described as their “oomph”—after exposure to the sprinkler systems and smoke. The insurers dispute the damage, as well as Perelman’s claim that he never attempted to sell the works afterward.

But how does a market, increasingly professionalised, complex and litigated, quantify a quality as elusive as “oomph”? And why does it take seven years—and millions in legal fees—to do so?

Part of the answer lies in the subjective nature of art valuation. Damage to a work is not always visible to the human eye. In many such cases, what is really on trial is evidence around how people reached conclusions or perceptions. It’s a challenge that is familiar from authenticity and attribution cases.

Perelman’s representatives argued that damage may not be immediately evident. That is, presenting findings from Jennifer Mass, the president of Scientific Analysis of Fine Art, his lawyers argued that damage from fire or damp could shorten the “lifespan” of a painting through damage to compounds which are as yet invisible.

The dispute is not without precedent. In the early 1990s the City of Amsterdam brought a claim against the US-based restorer Daniel Goldreyer after he worked on Barnett Newman’s Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III (1967-68), a painting that had been slashed by a vandal. Goldreyer was accused of concealing the extent of his restoration, which reportedly included repainting large areas—thereby, in the city’s view, damaging the translucency of Newman’s original. The case dragged on until 1997, when the two parties quietly settled.

More recently, debates have swirled around the authenticity and restoration of Salvator Mundi, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, which famously sold in 2017 for $450m. Critics argue that extensive restoration muddied the waters of attribution, even as the market enthusiastically embraced the work. Again, the debate focused less on physical condition and more on perception, and its impact on price.

In all these cases, by the time the dispute comes to trial, you are often left with a courtroom of experts with opposing, yet ultimately subjective, views.

Questions of attribution

“You are scratching a sore point in the art world. It is becoming more litigious, because of the increasingly high level of finances involved,” says the London-based art restorer Simon Gillespie, who adds that, in regard to providing opinions, “Increasingly, the experts and family foundations of the artists are closing the availability of attributing works, because of the expense of defending (or contesting) attributions. I’ve frequently heard that the amount of time it takes and money it costs make it easier to say no.”

Over long legal battles, markets shift, reputations evolve, and even opinions on how valuations are formed can change. That the Perelman trial has taken seven years is notable but not extraordinary. Some of the highest-profile disputes in recent memory have stretched over a decade, including the bitter feud between the Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev and the art adviser Yves Bouvier, which involved more than $1bn in disputed deals and ran between 2012 and 2024.

In Perelman’s case, timing has had clear commercial sensitivity. According to court filings, he had reportedly used the works (and many others since sold) as collateral for loans. Papers released during this dispute with insurers revealed that more than 70 works had been sold by his holding company following Deutsche Bank’s issuing of a margin call, where additional funds are required if an account falls below a certain threshold.

Lengthy trials can also complicate valuations being discussed. “An insurance policy outlines the specific terms under which a policyholder will be made whole in the event of a loss, including the type of value the appraiser should use to determine the object’s value,” says Linda Selvin, the executive director of the Appraisers Association of America. “When an appraiser is brought in, their role is to assess the value of the object(s) as of the date of the loss.” Selvin adds, “However, if the case proceeds to litigation, and market conditions have shifted since the loss occurred, either the claimant or the insurer may request an updated appraisal to reflect current market values.”

These prolonged timelines often reflect the domino effect: a single claim opens the door to discovery, which in turn triggers further litigation, third-party disputes and public scrutiny. In some cases, private institutions or individuals delay proceedings in the hope of avoiding disclosure of sensitive financial data or internal communications—another factor in the Perelman case, where efforts to shield documents from public view were unsuccessful.

Representatives from the parties in these cases did not respond to The Art Newspaper’s requests for comment by the time of publication.

More than 1,500 court documents have been filed, countless headlines written and substantial legal fees amassed on all sides. That one of the most high-profile valuation cases of the decade hinges on something as ephemeral as “oomph” is a fascinating insight into a world increasingly striving for structure, yet still so anchored in instinct.

The Trial at a Glance

Who: Ronald Perelman vs. multiple insurance companies (underwriters of Lloyds of London)

What: $410m insurance claim over alleged damage to five works by Cy Twombly, Ed Ruscha, Andy Warhol said to have occurred in a 2018 fire; trial began last month, after seven years of legal wrangling.

Perelman’s claim:

• Works lost their “oomph” through conditions linked to smoke and sprinkler exposure

• They have no visible fire damage, but he argues they have diminished market value

• Says he did not try to sell the works post-fire

Insurers’ defence:

• They dispute that any meaningful or “detectable” damage to the works occurred

• Perelman did try to sell some of the works

• The works’ combined value is just over $100m